As weather systems go, Jupiter's Great Red Spot is an interplanetary heavyweight. It could swallow the Earth whole and still have room for Mars.

Key points:

- NASA'S Juno spacecraft will fly over Jupiter's Great Red Spot at 12:06pm (AEST)

- The weather system is a 200-year-old hurricane that is 16,000km across

- Juno will provide the first ever close-up snaps of the solar system's biggest storm

And at 12:06pm (AEST) on Tuesday, NASA's Juno spacecraft hurtled right over the top of it.

The gargantuan hurricane has been raging for 200 years or more — and we've never been as close to it as the spacecraft came today.

Travelling at about 50 kilometres per second, Juno flew within 9,000km of the billowing brick-red cloud tops.

Prior to the encounter, the Juno mission's principal investigator, Scott Bolton from the Southwest Research Institute in Texas, said of the mission: "It's going to be incredible."

"We're basically just scraping along the top part of the atmosphere."

The storm itself is a good 16,000km across; Juno, if you include its outstretched solar panels, is the size of a tennis court.

"We're going screaming past, but we've got cameras that know how to work at that speed," Dr Bolton said.

"I can't wait to see what it looks like."

The team will have captured the first-ever close-up snaps of the solar system's biggest storm, but it will be hours yet until the team receives confirmation the mission was successful.

"Nobody knows exactly what kind of features we'll see inside, what the kind of colours and swirling of the clouds are," Dr Bolton said beforehand.

"Maybe we'll see something that looks three-dimensional, like a tunnel going in — nothing would surprise me at this point."

As it watched the Great Red Spot skid past, Juno also drifted upwards away from Jupiter because its closest approach — a mere 3,500km above the cloud tops — happened about 11 minutes earlier. If Jupiter were the size of a basketball, this venture brought it within millimetres of the surface.

'Through the gates of hell'

It's the sixth time the NASA probe has buzzed the giant planet since putting itself into a precise, lopsided orbit

almost exactly a year ago.

"There's high risk in every flyby. We're going through the gates of hell, every time," Dr Bolton said.

"And each time we go by, we're going through a worse region. More hazard, more radiation."

GIF:

Every orbit brings Juno between the radiation belts and within a few thousand kilometres of the surface.

Jupiter's magnetic field, 20,000 times stronger than Earth's, endows the gas giant with vast and punishing radiation belts Juno must thread a path between. So the probe's inner workings are shielded by a thick titanium wall, which has successfully withstood the onslaught so far.

Based on early calculations, Dr Bolton said, the team was confident Juno would succeed again — but the team did not take anything for granted.

"We will be on the edge of our seats, just keeping our fingers crossed that everything works and we get the close-up pictures that we all want," he said.

In order to have all its instruments staring down at Jupiter, during the flyby Juno faced the wrong way to communicate with Earth. It was expected to be a few hours before the team received confirmation the craft was intact and still functioning.

Then begins the process of downloading actual data: first from Juno's magnetometer, then from its camera. And the photos will be sent in chronological order, starting with the ones taken at greater distances.

The first close-up views of the Great Red Spot will not arrive until at least the weekend, according to Dr Bolton.

"You really have to learn patience when you're in this business. And it's patience during a time when you're very tense. I've learned that."

Seeking the secrets of a storm

When they do arrive, Juno's measurements will open a new chapter in our understanding of this famous anticyclone (so named because it spins in the opposite direction to most storms).

The Great Red Spot has been studied continuously since the early 1800s, and even some of the earliest views of Jupiter through telescopes, in the late 1600s, reported a big spot on its surface. Many astronomers think this was probably the very same storm.

What keeps a planet-sized hurricane spinning for 450+ years?

"That's a big puzzle; nobody knows," Dr Bolton said.

"There are some scientists who believe that in order for a storm to have lasted that long, it must have very deep roots. Maybe the source of energy that's creating that storm comes from deep inside the planet.

"Of course, up till now, we've only had the ability to look at the top part of Jupiter. We just see this thin veneer, which is gorgeous — it has these beautiful zones and belts, and this great storm on it, and a bunch of cyclones — but the key is what's underneath."

That is one of the strengths of the Juno mission: the craft carries a variety of instruments that are peering beneath Jupiter's clouds for the first time.

So its flyby this week should reveal the Red Spot's deep roots, if they exist.

The team will also be looking for lightning, which has been seen elsewhere on Jupiter and suggests the presence of water clouds.

"Lots of storms on Earth have a lot of lightning, but it usually takes water," Dr Bolton said.

"This storm may be more ammonia than water, but we don't know."

Enjoy it while it lasts

Juno's visit comes at an opportune time. After all those centuries, the Great Red Spot appears to be vanishing before our eyes and telescopes.

"It's been observed for hundreds of years, but now in the last couple of decades, we've noticed that it seems to be getting smaller and changing in shape," Dr Bolton said.

"So we may be catching it at the right time. It's always exciting when you can watch something in transition — you can learn a lot more."

Among their total of 32 planned orbits, Dr Bolton and his team hope to see Juno make at least two more passes of the Red Spot. That will depend on orbital calculations and — critically — where exactly the storm travels on the planet's surface. It's a moving target.

"In the future, we'll have a pass that looks more at the gravity shield, to see if there's a clump or a blob of mass underneath this thing. If it really has deep roots, there could be some deep mass that's underneath, that's moving around Jupiter with it," Dr Bolton said.

"Most people would think that's not possible, but I've learned not to be too confident guessing how Jupiter works. In the last year I've been surprised by so many things."

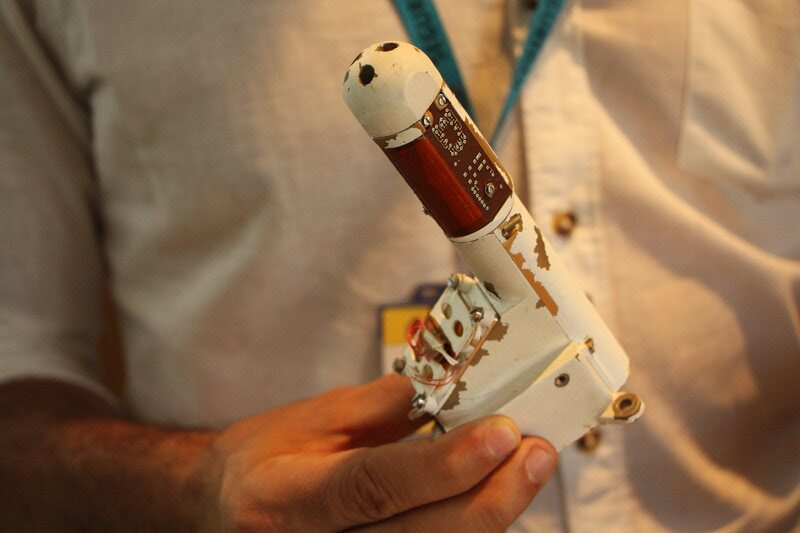

Rover Environmental Monitoring Station (REMS) tools on NASA’s Curiosity Mars.

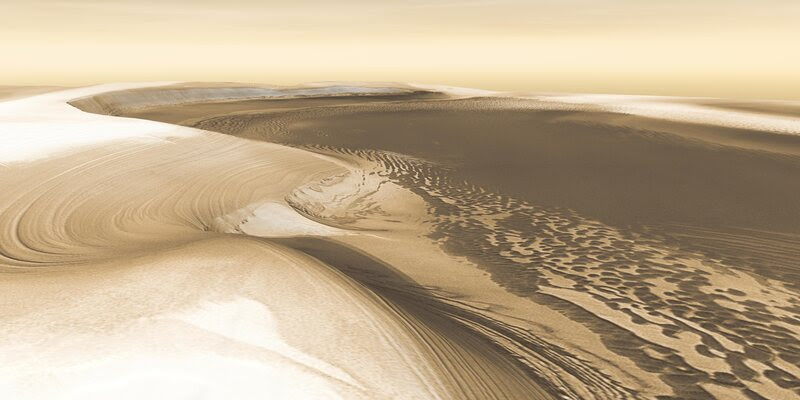

Rover Environmental Monitoring Station (REMS) tools on NASA’s Curiosity Mars. Chasma Boreale, a valley in Mars’ north polar ice cap.

Chasma Boreale, a valley in Mars’ north polar ice cap. A towering dust devil in the late-spring afternoon, Amazonis Planitia region of northern Mars.

A towering dust devil in the late-spring afternoon, Amazonis Planitia region of northern Mars. Jorge Pla-García at the Spanish National Center of Astrobiology.

Jorge Pla-García at the Spanish National Center of Astrobiology.  A View of Mars, showing ice clouds hanging above the Tharsis volcanoes.

A View of Mars, showing ice clouds hanging above the Tharsis volcanoes. Sand dunes in southern Terra Cimmeria showing the effects of Martian winds.

Sand dunes in southern Terra Cimmeria showing the effects of Martian winds. A Replica of REMS, used for tests on Earth.

A Replica of REMS, used for tests on Earth.  Installing one of the two mini-booms on the rover Curiosity that will monitor weather conditions on Mars

Installing one of the two mini-booms on the rover Curiosity that will monitor weather conditions on Mars