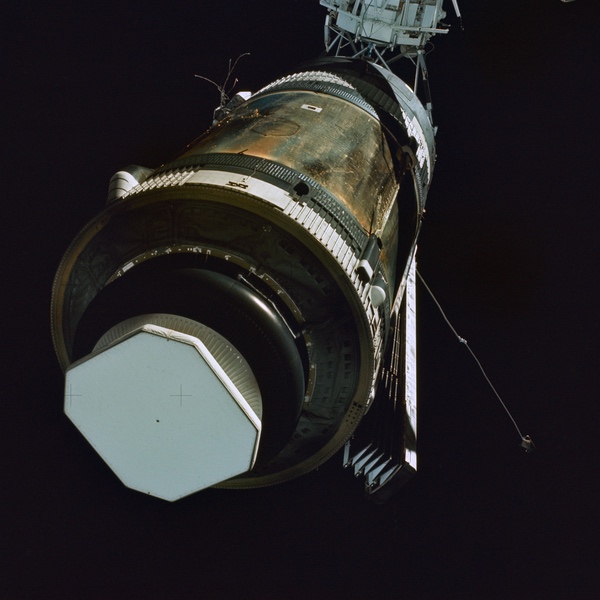

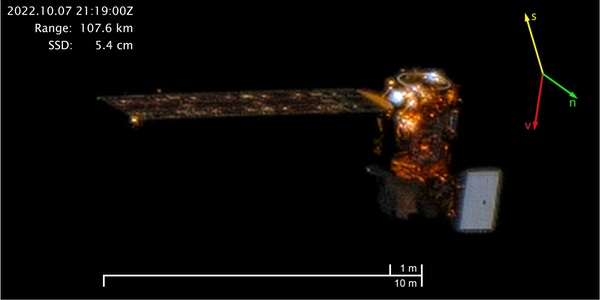

The Skylab orbital work shop, photographed by the crew that came to repair it. One of the two main solar panels was completely torn away, and the other was partially deployed, as seen here. A top secret reconnaissance satellite photographed the station shortly before the launch of the rescue mission, confirming the damage. (credit: NASA) |

Saving Skylab the top secret way

by Dwayne A. Day

Monday, May 22, 2023

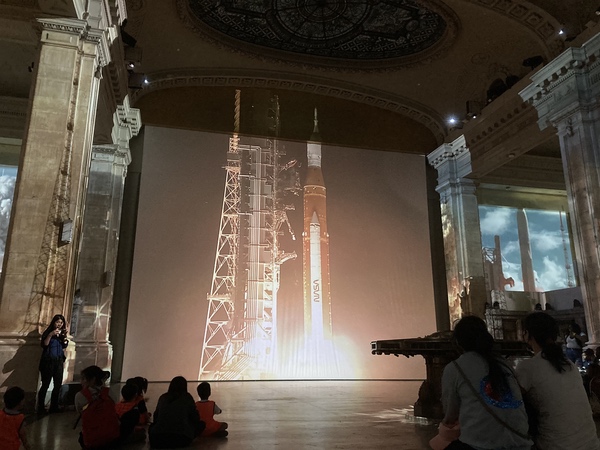

On May 14, 1973—50 years ago last week—NASA launched Skylab atop its last Saturn V. During liftoff, the workshop’s meteoroid shield broke loose and ripped off one of its two main solar panels. Problems were immediately apparent to NASA technicians monitoring the launch. Telemetry went bad soon after the ignition of the mighty Saturn’s second stage, and ground-based radars detected multiple pieces of debris coming off the station. Skylab entered orbit and jettisoned its large payload fairing as planned, but it was severely damaged.

Skylab was launched on the last Saturn V vehicle to lift off from Florida. (credit: NASA) |

NASA was aware of some of the damage to their expensive space station, although not all of it. Even without cameras aboard Skylab, they had enough data to figure out the broad outlines of the problems. For example, temperature sensors inside of Skylab indicated that it was very hot, a clue that the exterior insulation had been ripped off. The temperature was so high that ground controllers worried that some plastics inside the station might start to melt. The spacecraft still responded to commands from ground controllers to shift orientation and minimize solar heating, but it would have to be repaired before it could enter service—assuming that it could be repaired at all.

With limited data it was difficult for NASA to determine a repair plan. More data is always useful when dealing with unknown situations, and offers of help quickly came from the Department of Defense, which offered a ground-based radar based in the Pacific. But the most unusual assistance came from the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), which managed and operated the nation’s top secret intelligence collection satellites. On this day, May 22, half a century ago, the NRO was secretly helping NASA to save its crippled space station.

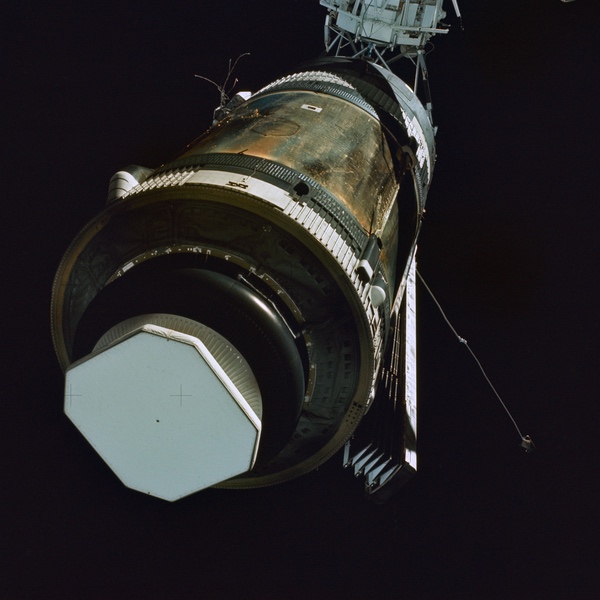

Skylab had a special shroud unique to that launch vehicle. The shroud covered the forward section of the workshop, which included the Apollo Telescope Mount and the docking ports. (credit: NASA) |

The Department of Defense steps up

The problems with Skylab were public immediately. Very quickly several national security organizations were either consulted or volunteered their assistance to NASA. One of them was the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). On Kwajalein Atoll in the Pacific Ocean DARPA operated a radar designated ALCOR, for ARPA Lincoln C-band Observables Radar. (The “D” had been added to ARPA only a year earlier.) NASA negotiated with DARPA about using the radar to image Skylab. The radar imaging capability was still not operational, but it was brought to bear quickly, collecting data the day after the launch and on two additional passes during the next few days. The radar data was transmitted to Lincoln Laboratory near Boston where it was processed and a final assessment was delivered to NASA around May 23. The radar indicated that one solar panel was missing and the other was partially deployed. It also confirmed that Skylab’s micrometeoroid shield was completely gone.

| The concept of imaging one satellite with another dates to the beginning of the Space Age. |

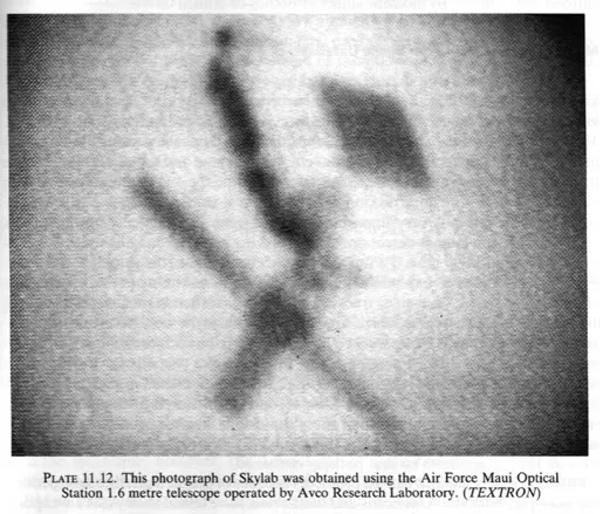

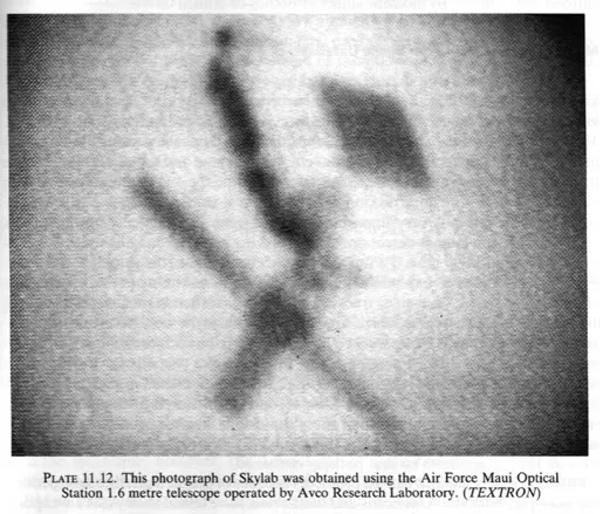

The US Air Force operated the Air Force Maui Optical Station (AMOS) on top of the Haleakala volcano on the island of Maui in the Hawaiian island chain. AMOS had multiple telescopes to track space objects, including a 1.6-meter diameter telescope. It is unknown if AMOS was used to image Skylab at that time, although the Air Force later released an AMOS image of the repaired Skylab. In the following years, AMOS would be upgraded with a system to compensate for atmospheric distortion, and then updated multiple times with new and improved telescopes. AMOS is still operational today, with a larger diameter telescope capable of taking impressive photos of objects in Earth orbit.

But there was another imaging capability available for Skylab, a much more secret one.

The Air Force Maui Observing Station (AMOS) had a telescope that was later used to image Skylab. It is unknown if AMOS was used to photograph the workshop soon after launch. A DARPA radar in the Pacific was used to image Skylab and may have provided data before the GAMBIT photograph was available. (credit: USAF) |

Sat-Squared

The concept of imaging one satellite with another dates to the beginning of the Space Age. One of the missions the Air Force envisioned for the Dyna-Soar spaceplane in the late 1950s was satellite inspection. Also in the late 1950s, the Air Force started a development program known as SAINT, for SAtellite INTerceptor. Although intended to destroy other satellites, one variant of SAINT would have been equipped with radar and a television camera for photographing satellites. SAINT was canceled in 1962 but was followed by another project in the mid-1960s to evaluate using an Agena spacecraft equipped with radar, other sensors, and cameras for inspecting satellites in orbit. That spacecraft included a variant that used film to take better quality photos, returning the film back to Earth, but the inspection satellite was not approved for development. Later in the 1960s, the Air Force’s Program 437 anti-satellite project included a satellite inspection variant that apparently successfully returned a film image of an Agena spacecraft in orbit. But no illustrations of the hardware have ever been declassified, nor has the inspection photograph.

By the mid-1960s, at least one CORONA reconnaissance satellite had unintentionally imaged another spacecraft in orbit, prompting NRO officials to begin evaluating if there was any intelligence value to this capability. CORONA’s cameras were not powerful enough to provide useful information about other spacecraft, but the GAMBIT-1 high resolution system which entered service in 1963 might have had that potential. However, there is no information indicating if GAMBIT-1 was used for this purpose before it was retired in 1967. Reconnaissance satellite imagery was classified with the code word “RUFF” at the time, and unusual or unexpected intelligence captured in the photographs was designated “RUFF Sensitive,” or “RSEN” for short. Satellite-to-satellite photography was known as “sat-squared” or “S2,” and became one of the RSEN categories.

Skylab already benefitted from a technology that had its origins in the NRO’s world. The station used control moment gyros, which had been developed in the mid-1960s for an NRO satellite program, probably a geosynchronous signals intelligence satellite, although this technology connection was not revealed until 2015. NASA operated in the glare of television lights, and its activities were reported regularly and instantly by the media. In contrast, the National Reconnaissance Office did not even publicly exist. It was “black”—highly classified—and its activities and capabilities were known only to a select few.

| Bradburn said he told the head of the National Reconnaissance Office that Skylab was not simply a NASA project, but an American project and it was in the best interests of the nation that Skylab not fail. |

Soon after the Skylab problems were known, Major General David Bradburn, who was then the head of the Secretary of the Air Force Special Projects (SAFSP) office, one of the NRO’s component offices and based in Los Angeles, quickly proposed using an NRO satellite to help save Skylab. Bradburn recommended to his superiors that a satellite readying for launch on May 16 at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California be used to take a photograph of Skylab to assist NASA in planning a repair mission. The satellite was known as a GAMBIT-3, and had been designed to take high-resolution photographs of the ground. The window of opportunity was tight: the manned Skylab 2 mission, which had now become a repair mission, was scheduled to launch on May 25, and Bradburn believed the NRO could get a photograph of Skylab to NASA before then. That short turnaround time between the two launches meant that the first phase of the GAMBIT’s photographic mission would have to be cut short to return the photos earlier than originally planned for the mission so they could be used for planning the repair mission.

According to Bradburn, who spoke about the incident during an Air Force history symposium in 1995, he told the head of the National Reconnaissance Office that Skylab was not simply a NASA project, but an American project and it was in the best interests of the nation that Skylab not fail. This justified using an intelligence satellite to help save it, even if that reduced some of the satellite’s intelligence collection. Bradburn’s proposal was approved by his superiors in the NRO, and presumably also by the Director of Central Intelligence and the Secretary of Defense.

Bradburn could propose this mission because for approximately six months a group of junior Air Force officers in his special projects office had been developing computer algorithms for using a GAMBIT-3 to photograph Soviet spacecraft. Their effort had been prompted by Soviet tests of an anti-satellite capability which had become operational in February 1973. The Air Force officers wanted the capability to take a photograph of a Soviet ASAT vehicle if one ever approached an American spacecraft. Because the computer programs were ready, the NRO could respond quickly to the Skylab problem—something that Bradburn was able to tell his superiors, and undoubtedly contributed to them approving the mission.

The Skylab shroud undergoing testing in Ohio. It separated as planned during flight, but a shield on the side of the workshop tore loose, causing significant damage. (credit: NASA) |

GAMBIT-3 was by then a well-proven spacecraft. The first GAMBIT-3 had launched in 1966 while the less-powerful GAMBIT-1 was still in service. It had a 175-inch (4.4-meter) focal length, and a camera that operated by pulling a large strip of black and white film past a narrow slit. The exposed film was then wound up at the front of the spacecraft inside a “bucket” protected by a heat shield. During a normal mission, when all the film was exposed after several days of operation, the bucket was ejected, fired a small retrorocket, and reentered Earth’s atmosphere. After deploying a parachute, it was captured in mid-air by an Air Force cargo plane hundreds of kilometers from Hawaii. At that point the satellite was junk and was commanded to reenter and burn up in the atmosphere.

By 1969 the NRO had added a second bucket to the spacecraft. This allowed the GAMBIT to take pictures, return them to Earth, and then go into sleep mode for a week or more before waking up to take some more pictures. The primary benefit of this second bucket was to extend the GAMBIT’s lifetime, although it did offer the opportunity to return pictures faster in a crisis situation without ending the entire mission early. It is unknown if the NRO ever de-orbited a bucket with film earlier than planned to take quicker advantage of its intelligence information, but that capability was known within the intelligence community by the early 1970s. GAMBIT had also become more flexible over the years, enabling it to be commanded to photograph targets of opportunity while in orbit.

Bradburn was not supposed to talk about any of this in 1995. He was not overly specific about the details, never mentioning the name of the still-classified GAMBIT program, for example. His remarks in 1995 were not repeated in the official proceedings of the conference. Although the US government has declassified information on satellite inspection programs like SAINT and Program 437AP, it has not officially released information on the use of GAMBIT during the Skylab incident.

Launch of a GAMBIT-3 high-resolution reconnaissance satellite. Only months before the launch of Skylab in May 1973, the National Reconnaissance Office developed the capability to use GAMBIT to photograph other satellites in orbit. A GAMBIT launched on May 16, 1973 was used to photograph Skylab and return its film to Earth in time to inform the repair mission. (credit: Peter Hunter Collection) |

Launch of the Black Bird

GAMBIT-3 number 38 launched as planned atop a Titan III-Agena D rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California on May 16, 1973. It quickly reached orbit and began operating its camera, probably taking photographs of targets inside the Soviet Union prior to reaching proper position to take a photo of Skylab.

According to independent satellite observer Ted Molczan, records from that era show that the closest approaches of the GAMBIT-3 and Skylab took place on May 18 and 19. The GAMBIT’s first satellite reentry vehicle de-orbited and was recovered over the ocean on May 21, so May 20 was probably the last possible day to image ground targets. Normally, a GAMBIT-3 would have operated its powerful camera taking photos of targets in the Soviet Union for up to a week or more before returning its first reentry vehicle and then going into a sleep mode for several weeks. With a launch on May 16 and a recovery on the 21st, the first part of this GAMBIT mission was cut short by several days in order to return the Skylab image in time for it to be used for the rescue mission.

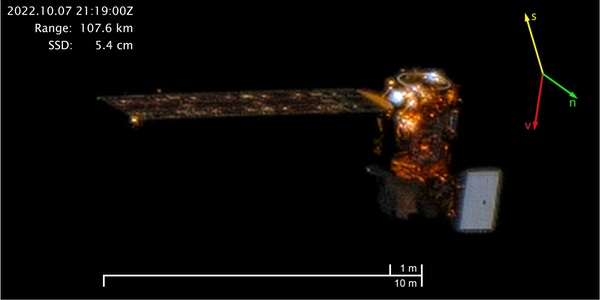

The photographs—assuming that the NRO attempted to photograph Skylab on both May 18 and 19—have not been declassified. Although the film returned to Earth on May 21, it would have taken a couple of days to get it to the processing center and develop it, meaning that it was probably available around May 23, around the same time as the final assessment of the ALCOR radar data. This was only a couple of days before the May 25 launch of Skylab 2 carrying astronauts Pete Conrad, Joseph Kerwin, and Paul Weitz. According to one person who saw a black and white image, the Skylab was only a small spot in the frame. It was also slightly blurry but still identifiable, and the photography was apparently still useable for NASA’s rescue mission.

| According to one person who saw a black and white image, the Skylab was only a small spot in the frame. It was also slightly blurry but still identifiable, and the photography was apparently still useable for NASA’s rescue mission. |

Based upon publicly available data, it is not clear exactly what NASA planners knew about Skylab’s condition and when they knew it. The initial reporting on Skylab indicates that NASA considered the situation dire and doubted that Skylab could be saved. On May 15, the New York Times reported that NASA believed that fixing any of the malfunctioning systems was impossible. Two days later, the Times indicated that the two main solar panels were not deployed and could not be repaired, and NASA believed that the only option was to have Skylab “borrow some electricity from the Apollo.” On May 18, the newspaper stated that NASA delayed the launch of the astronauts because Skylab “was found to be crippled—with its micrometeoroid and thermal shield ripped off and two of its solar arrays undeployed for converting sunlight into electricity.”

NASA Administrator James Fletcher at a briefing shortly before the launch of the repair mission. He is holding a model of the sunshield the astronauts would deploy over the portion of the station that had lost thermal shielding. (credit: NASA) |

But by May 22, the Times reported that NASA was “rehearsing techniques for fixing a broken solar panel.” Considering that the newspaper was reporting these facts a day after learning them, it seems that as early as May 18 or 19 NASA officials became aware that one of the solar panels was partially deployed. GAMBIT was still taking its photos and had not yet returned them to Earth. But perhaps preliminary ALCOR data indicated that there was reason to believe a rescue was possible.

Jim Oberg, who used to support NASA space missions, and is an expert on orbital rendezvous, notes that the Skylab rescue mission would have been in advanced planning stage by the time the GAMBIT-3 imagery was returned to Earth on May 21. “There don’t seem to be any indicators that major changes were made to these plans after obtaining the imagery” on May 23, Oberg wrote in an email. “The key feature that such imagery might have been able to contribute deals with the existing Skylab rescue plan.”

The plan was to fly the Apollo Command/Service Module alongside Skylab and have a crewman standing inside the Apollo try to pull the remaining solar panel wing loose with a grappling hook. “The critical missing data was the degree to which other torn off debris might still have been dangling outside, potentially flopping around right in the same volume through which the Apollo and its space suited harpooner would have to operate,” Oberg explained. “Knowing in advance that the space alongside Skylab appeared clear of large objects would have validated existing plans and lessened the need for elaborate contingency plans. In such a situation, from NASA’s point of view, no news—or rather, ‘news of nothing’—was good news.” GAMBIT’s photos could have provided that confidence.

Paul Fjeld was a young artist working for NASA during the Skylab mission. He drew artwork depicting the damaged station based upon a contractor's assessment of what happened. Just before the launch of the repair mission on May 25, he learned that NASA had new information about the state of the station. His artwork later appeared on national television. (credit: Paul Fjeld) |

The artist

Space artist Paul Fjeld was just starting his career in 1973 when he got an amazing opportunity to work with NASA at Mission Control in Houston to produce official illustrations of Skylab. Fjeld now lives in the suburbs of Washington, DC, and over many decades he produced paintings and other illustrations for contractors, the Canadian Space Agency, and NASA. “After the launch of the lab and we found out it was damaged and overheating,” Fjeld remembers, “I made two paintings for NASA public affairs showing a possible configuration of the Orbital Work Shop with the solar array beams (one partially deployed, the other pinioned to the side), and the micrometeoroid shield ripped away.” He wasn’t directly inside Mission Control, but he was working closely with NASA. “I did them based on some guesses from a Skylab engineer who worked the MacDac desk in the press center,” he recalls, referring to McDonnell Douglas Aircraft, a prime contractor for Skylab. “Over the ten days MSC was preparing the rescue plan and hardware, we'd get pressers. One I remember with Bill Schneider, the program manager, where he was asked about rumors of a spy camera that was imaging the OWS. He denied the rumors.”

| “The paintings were displayed in front of the big pre-launch press conference,” Fjeld recalled. “CBS grabbed them, and 25 million people saw my name as Walter Cronkite pointed stuff out over one of them.” |

There was intense media scrutiny on NASA at the time as the agency was struggling to demonstrate that it still had the moxie it had demonstrated during the recently-completed Apollo program. “The day before launch of the crew, my paintings were done and PAO wanted to authorize their accuracy, so I brought them into a private room and there was Bill. He liked them and told me what was wrong with them. He said the +Y SAS beam was completely gone and the other one deployed about 30 degrees,” Fjeld recalled. “This pissed me off because I wasted days of ‘analysis’ with the MacDac dude. Also he lied in the presser. But he was happy to have them released as official NASA.”

Despite his annoyance, Fjeld found that he was about to get the exposure every artist dreamt of. “The paintings were displayed in front of the big pre-launch press conference,” Fjeld recalled. “CBS grabbed them, and 25 million people saw my name as Walter Cronkite pointed stuff out over one of them.”

A few days after the May 25 launch, the astronauts freed the stuck solar panel in one of the most daring, and underrated, space missions ever flown. Conrad, Kerwin, and Weitz all went on to complete a successful mission on board the space station.

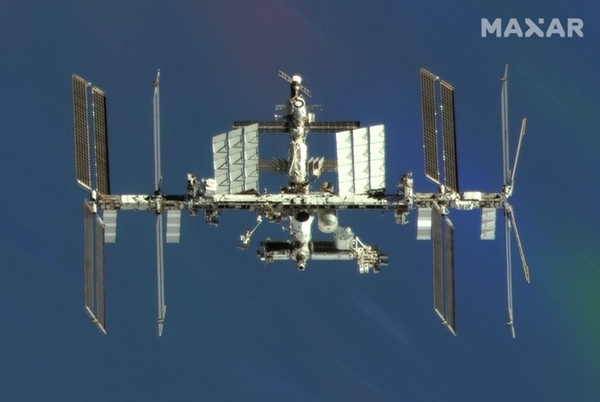

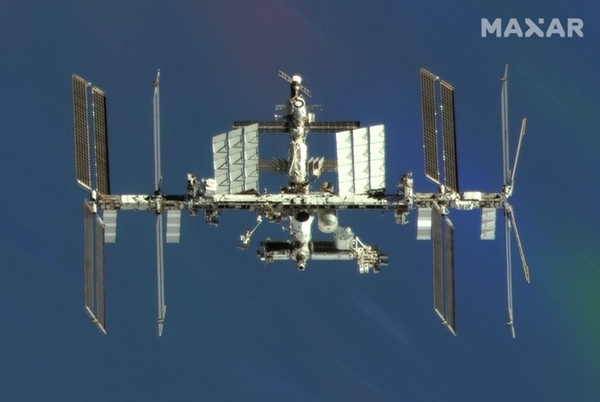

Maxar Technologies has the ability to photograph spacecraft using its commercial reconnaissance satellites. The company photographed the ISS in September 2022. (credit: Maxar) |

RSEN

Considering that the GAMBIT strip camera had been designed to photograph a ground target, matching the film speed to a moving spacecraft in an entirely different orbit must have been challenging. It certainly involved a lot of math. But the mission contributed to the rescue of a billion-dollar space project—and it also secretly demonstrated that not even Soviet satellites could hide from the prying eyes of American spysats.

After this event, the United States further developed so-called satellite-to-satellite (or “sat-squared”) imaging capability. According to one person familiar with the subject, a later GAMBIT-3 mission took an incredibly detailed photograph of Kosmos 1267, an unmanned spacecraft that rendezvoused and docked with the Salyut-6 space station in spring 1981. The GAMBIT-3 program was declassified in September 2011 and the National Reconnaissance Office released significant amounts of information about its technology and its operations, including several official histories of the program as well as some imagery, degraded to not reveal its impressive capabilities. The official histories had some deletions, however, including a section that most likely referred to the Skylab incident. In 2015, a declassified report about the canceled Manned Orbiting Laboratory included a deleted section that almost certainly discussed the ability of MOL’s powerful DORIAN optical system to image other spacecraft in orbit.

The last GAMBIT-3 was launched in 1984. By late 1976 the NRO began operating a new series of satellites known as the KH-11 KENNEN, which did not require film and could transmit imagery to a ground station. KENNEN provided much greater flexibility, particularly for satellite-to-satellite imaging. Kennen is the Middle English word for “to perceive.”

In April 1981, the space shuttle Columbia roared off its launch pad in Florida into a clear blue sky. One of the revolutionary aspects of the shuttle’s design was its thermal protection system consisting of tens of thousands of ceramic tiles coating the orbiter’s underside. Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo spacecraft had all gone into orbit with their heatshields covered, protected. The orbiter’s heat shield was exposed, and fragile, and that had people worried. In fact, it had NASA officials so worried that they enlisted the help of the National Reconnaissance Office, and its top secret tool, the KENNEN reconnaissance satellite. Not long after Columbia’s launch there were rumors that a KH-11 had been used to image the orbiter. Journalists knew that NASA engineers were concerned about Columbia’s tiles, yet NASA officials declared that they knew the shuttle was safe for reentry.

| Skylab is long gone, and increasingly forgotten. But it owed some of its success to a spacecraft that spent all its time in the dark. |

The use of the KENNEN to image Columbia and determine that the tiles were intact was eventually confirmed by author Rowland White in the 2018 paperback version of his book Into the Black. White’s book was originally published in the UK in late 2015 and the United States a few months later. The hardcover edition of Into the Black had the overall basics of the imaging effort, although not specific details. Even though White did not extensively document his sources, it was not difficult to read between the lines and determine that for the first edition, White had relied primarily on published—and speculative—sources about the event. White’s account in the hardcover version implied that the imaging effort had largely been ad hoc, perhaps even arranged at the last minute.

White conducted additional research after the publication of the hardcover version, talking to at least one new source with first-hand knowledge. The new account was based upon the memories of one of the people who was directly involved in the imaging effort, NASA engineer Ken Young. Rather than an ad hoc effort like using the GAMBIT during Skylab, the use of the KENNEN to image the shuttle had been planned over a year before the flight. Young had been working on the shuttle program at the Johnson Space Center when he was told that he needed to obtain a top secret compartmented clearance for a new assignment. After getting the clearance, he started regularly meeting with NRO representatives to work on coordinating the shuttle’s low inclination orbit with a KENNEN satellite in polar orbit.

Maxar has used one of its satellites to photograph another one of its satellites that was damaged by orbital debris, determining that the damage was minimal. Here the company imaged the Landsat-8 satellite in orbit. (credit: Maxar) |

According to White, the launch was delayed a short time to improve the imaging opportunity. Also, the KH-11 suffered a problem that threatened its ability to take its picture. The astronauts onboard Columbia also apparently glimpsed the satellite in the distance. White recounted how impressed Young was with the equipment and facilities he saw when he was first brought onto the project. Clearly a lot of money was being spent on satellite intelligence systems.

Today some non-American satellites have demonstrated the ability to photograph or image with radar other satellites, so the technology has clearly proliferated. For example, in 1998, the French Spot-4 satellite photographed the European Space Agency’s ERS-1 satellite.

In recent years, this capability took another major step into the commercial world. In 2016, after Maxar Technologies’ Worldview-2 satellite was damaged by debris, the company used another of its satellites to image Worldview-2 and determined that the damage was minimal. Maxar has also used a satellite to image the International Space Station. Although Maxar has had this capability for the better part of a decade, the company has been judicious in releasing images, only doing so for American satellites. Last month, Maxar released an image of NASA’s Landsat-8 satellite photographed by the company’s Worldview-3 satellite. The ISS and Landsat images were taken in fall 2022. It is unclear how Maxar will offer this capability commercially. For instance, could an American citizen order photographs of Russian and Chinese military spacecraft in orbit?

Satellite inspection and imaging is now becoming more common and more public, even as its origins remain murky. Skylab is long gone, and increasingly forgotten. But it owed some of its success to a spacecraft that spent all its time in the dark.

Acknowledgement: The author wishes to thank NW and WB who commented on a draft of this article.

Dwayne Day is interested in hearing from anybody involved in the Skylab imaging efforts. He can be reached at zirconic1@cox.net.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.