Since I was a young child Mars held a special fascination for me. It was so close and yet so faraway. I have never doubted that it once had advanced life and still has remnants of that life now. I am a dedicated member of the Mars Society,Norcal Mars Society National Space Society, Planetary Society, And the SETI Institute. I am a supporter of Explore Mars, Inc. I'm a great admirer of Elon Musk and SpaceX. I have a strong feeling that Space X will send a human to Mars first.

Thursday, December 29, 2022

Tuesday, December 27, 2022

Monday, December 26, 2022

Sunday, December 25, 2022

Thursday, December 22, 2022

Wednesday, December 21, 2022

Monday, December 19, 2022

Saturday, December 17, 2022

Thursday, December 15, 2022

Wednesday, December 14, 2022

Dr, Sian Proctor Named Astronaut Ambassador For Explore Mars, Inc.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tuesday, December 13, 2022

Review Of The Book Before The Bang

|

Review: Before The Big Bang

by Jeff Foust

Monday, December 12, 2022

Before The Big Bang: The Origin of the Universe and What Lies Beyond

by Laura Mersini-Houghton

Mariner Books, 2022

hardcover, 240 pp., illus.

ISBN 978-1-328-55711-7

US$27.99

Last week, NASA announced that astronomers, using spectroscopic data from the James Webb Space Telescope, had confirmed that some early galaxies the telescope had detected dated back to just 350 million years after the Big Bang. That makes the galaxies the oldest detected to date as astronomers seek to push back the curtain shrouding the early universe.

While the discovery—still going through the peer-review process, NASA advised—is a major step in astronomy, it still offers few insights about the Big Bang itself. That includes what happened in the earliest instants after the Big Bang, critical to the later formation of stars, galaxies, and broader structure in the universe, but also why the universe itself exists in the first place, and why it seems, to some, to be particularly “fine-tuned” for life.

| “The spontaneous formation of a brain in empty space stands a much better chance (statistically) of occurring than the creation of our universe through cosmic inflation,” she writes. |

Those are questions that Laura Mersini-Houghton, a theoretical physicist and cosmologist at the University of North Carolina, has been studying throughout her career. In Before The Big Bang, she discusses one potential solution to those questions, a topic she pioneered and is now gaining traction in the broader physics field: that out universe is part of a much larger multiverse.

Mersini-Houghton was motivated to pursue this topic because of a sticking point in the widely accepted model of cosmic inflation. While inflation explains the initial expansion of the universe after the Big Bang, “the infant universe must have been a remarkably unusual state of exceptional order” for it to turn out in this way, she writes. How unusual? “The spontaneous formation of a brain in empty space stands a much better chance (statistically) of occurring than the creation of our universe through cosmic inflation.”

That seems like a problem to her, so she studied it for much of her career, even though the issue was at the outskirts of mainstream thought in cosmology and astrophysics. The solution that she and a few colleagues developed involved string theory, specially something called the string-theory landscape. That provides, she writes, “a vast collection of initial energies—of potential Big Bang energies—capable of jump-starting multiple universes.”

That led them down the path of the multiverse concept, including the realization that our particular set of initial conditions is actually favored: “there is absolutely nothing special or exclusive about our beginning.” That model does have some testable hypotheses, such as features in the cosmic microwave background that could be created by entanglement with other universes immediately after the Big Bang. The concept of a multiverse now has much broader acceptance, she notes, something that occurred even during the process of writing the book.

The concepts in Before The Big Bang can be difficult to grasp at times, from quantum entanglement to 11-dimension string theory (that’s true “even for seasoned physicists,” she notes.) She avoids equations and mathematics to make it a little less challenging. She also weaves in anecdotes from her life, particularly growing up in Albania when the country was a repressive, isolated Communist regime, which shaped her career (“in light of my childhood experiences in Albania, the decision to research the creation of the universe didn’t feel like a particularly courageous act,” she writes of her decision to pursue that particular field.) The book is an enlightening read about the formation of our universe and the mysteries that still remain about how we got here.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

The First Great Photo Of The Earth In 50 Years

The “Blue Marble” image from Apollo 17 is one of the most iconic images in history. (credit: NASA) |

The first photograph of the entire globe: 50 years on, Blue Marble still inspires

by Chari Larsson

Monday, December 12, 2022

December 7 marked the 50th anniversary of the Blue Marble photograph. The crew of NASA’s Apollo 17 spacecraft—the last human mission to the Moon—took a photograph of Earth and changed the way we visualized our planet forever.

| By removing the graticule—the grid of meridians and parallels humans place over the globe—the image represented an Earth freed from mapping practices that had been in place for hundreds of years. |

Taken with a Hasselblad film camera, it was the first photograph taken of the whole round Earth and is believed to be the most reproduced image of all time. Up until this point, our view of ourselves had been disconnected and fragmented: there was no way to visualize the planet in its entirety.

The Apollo 17 crew were on their way to the moon when the photograph was captured 29,000 kilometers from the Earth. It quickly became a symbol of harmony and unity.

The previous Apollo missions had taken photographs of the Earth in part shadow. Earthrise shows a partial Earth, rising up from the Moon’s surface.

In Blue Marble, the Earth appears in the center of the frame, floating in space. It is possible to clearly see the African continent, as well as Antarctica’s south polar ice cap.

Photographs like Blue Marble are quite hard to capture. To see the Earth as a full globe floating in space, lighting needs to be calculated carefully. The sun needs to be directly behind you. Astronaut Scott Kelly observes that this can be difficult to plan for when orbiting at high speeds.

Produced against a broader cultural and political context of the “space race” between the United States and the Soviet Union, the photograph revealed an unexpectedly neutral view of Earth with no borders.

Disruption to mapping conventions

According to geographer Denis Cosgrove, the Blue Marble disrupted Western conventions for mapping and cartography. By removing the graticule—the grid of meridians and parallels humans place over the globe—the image represented an Earth freed from mapping practices that had been in place for hundreds of years.

The photograph also gave Africa a central position in the representation of the world, whereas Eurocentric mapping practice had tended to reduce Africa’s scale.

The image quickly became a symbol of harmony and unity. Instead of offering proof of America’s supremacy, the photograph fostered a sense of global interconnectedness.

Since the Enlightenment, mapping and map making had emphasized man’s superiority over the Earth. Working against this hierarchy, Blue Marble evoked a sense of humility. Earth appeared extremely fragile and in need of protection. In his book Earthrise, Robert Poole wrote: “Although no one found the words to say so at the time, the ‘Blue marble’ was a photographic manifesto for global justice.”

The “2002 Blue Marble” was a composite based on images from Earth science satellites. (credit: NASA/Robert Simmon and Reto Stöckli) |

Blue Marble’s afterlives

It is impossible to examine Blue Marble and separate it from the urgency of today’s climate crisis.

It quickly became a symbol of the early environmental movement, and was adopted by activist groups such as Friends of the Earth and annual events such as Earth Day.The photograph appeared on the cover of James Lovelock’s book Gaia (1979), postage stamps, and an early opening sequence of Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth (2006).

| Advances in technology might help explain the photograph’s enduring charm from the vantage point of 2022. The first photograph of our planet was remarkably lo-fi. |

The ways we have viewed and visualized Earth have changed over the decades. Starting in the 1990s, NASA created digitally manipulated whole-Earth images titled Blue Marble: Next Generation, in honor of the original Apollo 17 mission. These are composite images composed of data stitched together from thousands of images taken at different times by satellites.

Space-based imaging technology has continued to advance in its capacity to render astonishing detail. Art historians such as Elizabeth A. Kessler have linked these new generation of images picturing the cosmos with the philosophical concept of the sublime.

The photographs create a sense of vastness and awe that can leave the spectator overwhelmed, akin to 19th century Romantic paintings such as Thomas Moran’s The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone (1872).

In 1995, the Hubble Space Telescope revealed mountains of gas and dust in the Eagle Nebula. Known as the Pillars of Creation, the image captures gas and dust in the process of creating new stars.

Earlier this year, NASA released the first images taken by the James Webb Space Telescope. Building on Hubble’s discoveries, JWST is designed to visualize infrared wavelengths at an unprecedented level of clarity.

These advances in technology might help explain the photograph’s enduring charm from the vantage point of 2022. The first photograph of our planet was remarkably lo-fi. Blue Marble is the last full Earth photograph taken by an actual human using analogue film: developed in a darkroom when the crew returned to Earth.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Chari Larsson is a senior lecturer of art history at Griffith University in Australia.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

The Orion Capsule Returns To Earth!!

The Orion crew capsule descending under its parachutes just before splashdown December 11. (credit: NASA) |

All’s well that finally begins well

by Jeff Foust

Monday, December 12, 2022

December 11, 1972, featured a landing that marked the beginning of an ending. The Apollo 17 Lunar Module, Challenger, touched down on the surface of the Moon in the Taurus-Littrow region, delivering astronauts Gene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt for the sixth and most ambitious—but also final—Apollo lunar landing mission. The astronauts would spend the next three days on the Moon, conducting three moonwalks that, to this day, mark the last time humans have walked on the lunar surface.

December 11, 2022, featured a landing that was the ending of a beginning. Fifty years to the day after Challenger touched down at Taurus-Littrow, an uncrewed NASA Orion crew capsule splashed down in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Baja California. The splashdown marked the successful conclusion of the Artemis 1 mission and the strongest sign to date that NASA’s long awaited, and long delayed, return to the Moon, was on track.

| “We all came into the mission expecting to have challenges, and the team went through a lot of simulations and tests to be ready for the bad days, and instead it’s kind of purring along,” said Scoville. |

The uncrewed mission lifted off November 16 on the first flight of the Space Launch System (see “SLS showed up, at last”, The Space Review, November 21, 2022), with the rocket’s upper stage propelling Orion towards the Moon. After the launch, Orion performed four major maneuvers: a powered lunar flyby November 21 to send the spacecraft towards a distant retrograde orbit (DRO) around the Moon, a November 25 maneuver to enter DRO, a December 1 burn to leave DRO, and then another powered flyby of the Moon December 5 that put the spacecraft on a trajectory back to the Earth.

Artemis 1 was designed to be a shakedown cruise for the Orion spacecraft, putting it through its paces in cislunar space to show it was ready to carry astronauts. NASA officials, at many briefings held over the 25½-day mission, discussed “stressing” the spacecraft to see what worked, and what didn’t, before flying astronauts on Artemis 2 and subsequent missions.

By and large, the spacecraft passed those tests. “We all came into the mission expecting to have challenges, and the team went through a lot of simulations and tests to be ready for the bad days, and instead it’s kind of purring along,” said Zeb Scoville, deputy chief flight director, at one briefing. “The discussions we’re having is how to rev the engines a little a bit harder and how to push it.”

That extra revving of the engines came in the form of additional flight test objectives added during the course of the mission. There were 124 objectives originally planned, but as the mission progressed and engineers found few issues to deal with, they added over a dozen while in DRO and on the way back to Earth, such as testing the spacecraft’s thermal characteristics in different attitudes and performance of a valve in the propulsion system, all to further buy down risk for future crewed missions.

The mission was not problem free, but the issues they countered, project officials said, were mostly minor. The most persistent one was with devices called latching current limiters, a kind of circuit breaker in one part of the spacecraft’s power system. Those devices opened repeatedly over the course of the mission despite not being commanded to do so.

Engineers with ESA and Airbus, which built the service module, spent the final days of the mission performing what tests they could before the module was jettisoned just before reentry. “We don’t have an idea of what is the root cause. We are investigating, looking at all possible options,” said Philippe Deloo, ESA program manager for the service module, at a briefing two days before splashdown. He said possibilities included electromagnetic interference in the power system or from spacecraft antennas.

However, he and his Airbus counterpart, Ralf Zimmermann, emphasized the issue was a minor one, since the devices could be commanded to close whenever they opened, and affected only a small part of the overall power system. “It is a glitch, not a mission-critical failure,” said Zimmerman

The biggest test, though, would come at the end. NASA set out four top-level priorities for the Artemis 1 mission. The second of the four was to test out Orion systems in space, while the fourth was to perform miscellaneous tests and activities during the mission, and accounted for those 124+ objectives during the mission. The top priority, though, was to successfully test Orion’s heat shield by reentering at lunar return velocities, approaching 40,000 kilometers per hour. (The third priority, tied closely to the first, was to recover Orion after splashdown from that reentry.)

The reentry was the top priority given the critical nature of the heat shield and the fact it could not be tested on the ground. “There is no arcjet or aerothermal facility here on Earth of replicating hypersonic reentry with a heat shield of this size,” said Mike Sarafin, NASA Artemis 1 mission manager, a few days before splashdown. “It is a safety-critical piece of equipment. It is designed to protect the spacecraft and the passengers, the astronauts on board. So, the heat shield needs to work.”

The reentry, unlike the Apollo lunar returns, would use a “skip” technique where the capsule descends part way into the atmosphere, then ascends again to the edge of the atmosphere before reentering. That is designed to moderate the g loads on spacecraft occupants as well as provide more flexibility in selecting a landing location. (NASA, in fact, had to move the splashdown location by about 550 kilometers to the south because of a forecast of winds and rain at the primary location just west of San Diego.)

So, on December 11, NASA eagerly, and anxiously, followed Orion’s return. At 12pm EST, right on schedule, the crew capsule separated from the service module; the latter, having completed its mission, burned up in the atmosphere with any surviving pieces falling in the South Pacific west of Peru. Twenty minutes later, Orion reached the imaginary boundary dubbed the “entry interface” at the top of the atmosphere deemed the start of reentry.

| “This is what mission success looks like, folks,” Sarafin said. |

The skip reentry meant there would be not one but two blackout periods where the plasma surrounding the spacecraft would prevent communications. Each time Orion emerged on schedule and in good condition. It continued its descent, slowing as first drogues and then three main parachutes deployed. At 12:40pm, it splashed down within sight of the recovery ship, USS Portland, coming within 3.9 kilometers of the target (the mission requirement was an accuracy of 10 kilometers.)

At a briefing a few hours after splashdown, even as crews from the Portland were still working to bring the capsule into the ship after some post-splashdown tests, NASA officials were elated.

“This is what mission success looks like, folks,” Sarafin said. “We had a very successful flight test. We now have a foundational deep space transportation system.”

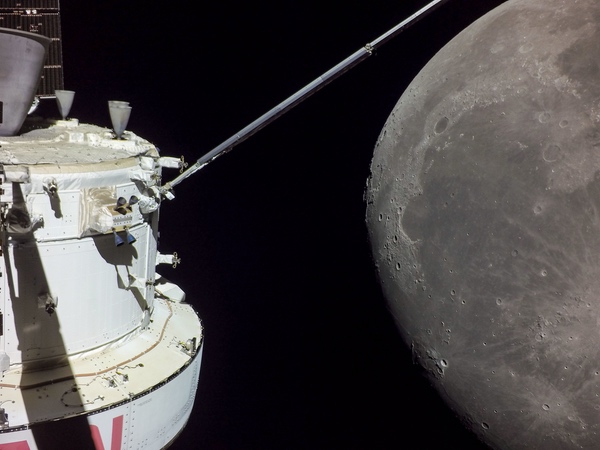

Orion as it flew by the Moon on its way back to Earth December 15. (credit: NASA) |

Future plans

Sarafin and others at the post-splashdown briefing stressed that they were only starting to review the data from reentry, or even the mission in general. That included data from reentry collected during the blackout period and stored on the spacecraft. “Initial indications are very favorable, but there’s more ahead of us in terms of exactly understanding what the reentry flight test told us,” Sarafin said.

It was clear, though, that they were pleased with what they knew so far. “I would say we’re very happy with what we’ve seen so far on the heat shield,” said Howard Hu, NASA Orion program manager.

USS Portland, with Orion on board, will arrive in San Diego December 13. NASA expects to transport the capsule cross-country to the Kennedy Space Center by the end of the month for further studies.

Technicians will also remove several avionics units from the capsule, such as inertial measurement units and phased-array antennas. Those will be refurbished and reflown on the Orion flying Artemis 2. (Had they not been recovered, or if they can’t be reused for some reason, Hu said, they can turn to units that are being produced for the Orion flying Artemis 3.)

That puts a limit on how soon the next mission can fly, even if the rest of the Orion spacecraft and the next SLS are ready to go. Before Artemis 1, NASA estimated that Artemis 2 would be ready to fly about two years after Artemis 1.

Immediately after splashdown, NASA was sticking to that schedule. “Right now, we’re still looking at that two-year timeframe from Artemis 1 to 2,” said Jim Free, NASA associate administrator for exploration systems development.

“One thing we’ve always been concerned about is what do we learn from [Artemis] 1 and are there changes we have to make,” he continued. “We have learned a lot from 1. TBD if there’s any changes.”

“We obviously want to try and do it quicker,” he added, including lessons learned from processing Artemis 1.

| “Right now, we’re still looking at that two-year timeframe from Artemis 1 to 2,” said Free. “We obviously want to try and do it quicker.” |

NASA’s leadership, though, wasn’t concerned about losing the momentum built up by the success of the Artemis 1 mission over the next two years. “I’m not worried about the support from Congress,” administrator Bill Nelson said. “We will have that. We, in fact, have that.”

“I believe you will see continued talk about what’s going on when Vanessa announces who is on the crew,” he added, referring to Johnson Space Center director Vanessa Wyche. Earlier in the briefing, she said the agency had held off naming the crew on Artemis 2 until it saw what happened with Artemis 1, to avoid naming the crew too soon if there were problems. With Artemis 1 an apparent success, she said, that crew could be named in early 2023.

“That’s going to be an immediate story,” he said of the crew announcement, suggesting the public would be as interested in the four astronauts (one of which will be from Canada, as part of an agreement where Canada provides a robotic arm system for the lunar Gateway) as it was more than 60 years ago when NASA named the Mercury 7.

“Naturally, we would be concerned if that interest waned,” he added.

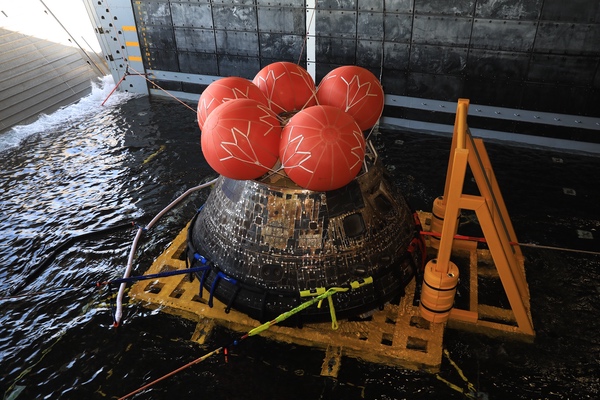

Orion sitting inside the well deck of the USS Portland after splashdown. (credit: NASA) |

Forgetting past problems

The splashdown of Orion to conclude Artemis 1 was widely heralded by politicians, space agency leaders and others. People from different ends of the political spectrum, for example, came to the same conclusion about the mission.

“I applaud the NASA team for their work on completing a successful Artemis I mission. We’re one step closer to returning astronauts to the moon,” said Vice President Kamala Harris in a tweet after splashdown.

“Success! We are one giant leap closer to returning Americans to the Moon and a new era of deep space exploration,” said Rep. Brian Babin (R-TX), ranking member of the House space subcommittee, in another tweet.

Nelson, at the post-splashdown briefing, was not surprised. “NASA is basically nonpartisan,” he said, reiterating a point he often made during his three terms in the Senate. “R’s and D’s alike come together and join us.”

There was, in those salutes to the mission after splashdown, little, if any, mention of the problems that the program had suffered for years leading up to that point: nothing about the lengthy delays, high costs, or various technical problems suffered over the years. Success has a way of making people forget those past problems.

This is not the first time this has happened to NASA even this year. The James Webb Space Telescope has long been the subject of criticism for its major cost overruns and schedule delays. Yet, by the time it released its first images in July after a successful launch and commissioning over the previous six months, there was nothing but praise for JWST (see “The transformation of JWST”, The Space Review, July 18, 2022).

Success, it seems, can excuse, or at least make people forget, those past problems. All’s well that ends well—or perhaps, since both JWST and Artemis are only now getting started after years of development, all’s well that finally begins well.

| “I think that when we have private launch capabilities that rival this we should transition, and that will make me feel a lot better about the future and the future success of Artemis,” Garver said. |

However, the experiences of Artemis and JWST may not be the same going forward. For the space telescope, its costs are largely behind it: NASA still spends money to operate it and support science from it, but that will be a small fraction of the $10 billion that NASA and its partners spent to build and launch it. Moreover, it will be generating results continuously over potentially 20 years, with a steady stream of both striking images and compelling science already emerging from the mission.

NASA, though, still has to bear significant costs to build future SLS rockets and Orion spacecraft, along with other components of the overall Artemis campaign: ground equipment like a second mobile launcher (which has suffered its own serious cost and schedule problems), the lunar Gateway, and other elements. And, unlike the steady cadence of JWST images, the next Artemis launch is at least two years away.

NASA says its working to reduce the costs of Artemis over the long run, with a long-term contract in place with Lockheed Martin for later Orion spacecraft and a proposed similar contract with a Boeing-Northrop Grumman partnership for SLS. That’s intended to secure the future of those vehicles for Artemis missions well into the next decade.

“I think one of the biggest achievements is that there’s a lot of hardware here that has been under development for a long time,” former NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine said at a SpaceNews event last week. “The Artemis program just gave all that hardware a mission, which is what we needed in order to get to where we are today.”

Lori Garver, former NASA deputy administrator, also commended the agency at the event for the success of the mission, but was skeptical that current approach was the right one for Artemis in the long term, particularly as commercial options emerge.

“I do not believe that the country can or should probably spend the amount of money we are on launch infrastructure over the longer term,” she said. “I think that when we have private launch capabilities that rival this we should transition, and that will make me feel a lot better about the future and the future success of Artemis.”

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Sunday, December 11, 2022

Saturday, December 10, 2022

Friday, December 9, 2022

Wednesday, December 7, 2022

Tuesday, December 6, 2022

Two New Minerals Discovered In A Meteorite

DISCOVERIES

Off the Charts

Scientists discovered two new minerals never before seen on Earth inside a large meteorite, a finding that could hold important clues about how space rocks form, Live Science reported.

Researchers at the University of Alberta in Canada came across the minerals inside a single 2.5-ounce slice taken from the 16.5-ton El Ali meteorite which was found in 2020 in Somalia.

They were able to quickly identify the minerals as new by comparing them with similar synthetic versions that had previously been made in a lab.

The team explained that El Ali was a type of meteorite made from meteoric iron flecked with tiny chunks of silicates – known as an “Iron, IAB” complex meteorite.

The new findings were named elaliite – after the meteor – and elkinstantonite after Lindy Elkins-Tanton: She is the principal investigator of NASA’s upcoming Psyche mission, which plans to send a probe to investigate the mineral-rich Psyche asteroid for evidence of how our solar system’s planets formed.

Researchers are planning to also analyze the space chunks to determine the conditions under which the meteorite formed.

They are also looking for ways as to how the unique minerals could be used on Earth, USA Today noted.

“Whenever there’s a new material that’s known, material scientists are interested, too, because of the potential uses in a wide range of things in society,” Chris Herd, curator of the University of Alberta’s Meteorite Collection, said.

Monday, December 5, 2022

Saturday, December 3, 2022

Friday, December 2, 2022

Wednesday, November 30, 2022

Tuesday, November 29, 2022

Monday, November 28, 2022

Sunday, November 27, 2022

Saturday, November 26, 2022

Friday, November 25, 2022

Book Review Art Of The Cosmos

|

Review: The Art of the Cosmos

by Jeff Foust

Monday, November 21, 2022

The Art of the Cosmos: Visions from the Frontier of Deep Space Exploration

by Jim Bell

Union Square & Co., 2022

hardcover, 224 pp., illus.

ISBN 9781-4549-4608-3

US$35.00

There’s no shortage of books published over the years that have illustrated the beauty of the universe. Often they’re large-format books with glossy pages and colorful images of galaxies, nebulae, planets, and moons, attracting the reader. The imagery is beautiful—like works of art—but they’re intended primarily to illustrate the science of the solar system or the universe.

In The Art of the Cosmos, planetary scientist Jim Bell embraces the artistic aspect of those images. “If one of the roles of art is to extend our senses and our experiences into the realm of the unknown and the unfamiliar, to imbue us with a sense of awe and wonder at the glory and grandeur of nature, and to push the boundaries of what we know and feel,” he writes in the book’s introduction, “then deep space exploration has provided some of the most spectacular and humbling kinds of art that humans have ever produced.”

| Bell believes that “deep space exploration has provided some of the most spectacular and humbling kinds of art that humans have ever produced.” |

In the book, he gathers more than 125 examples of such art, primarily photographs, that stand out as examples of cosmic art. They range from a sunset on Mars, tinged with shades of blue rather than orange and red, to a kilometer-high cliff on Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko that draws parallels to El Capitan in Yosemite, to the Flame Nebula, its dark red dust contrasting with the bluish glow of ionized hydrogen.

Bell selected images that he said hewed to many of the characteristics of terrestrial art, like composition, lighting, and perspective. Those elements may be accidents of planned observations by spacecraft or telescopes, but in some cases, like the Martian sunset, planned at least with the potential for aesthetics as well as science. Many of the images in the book are products of sophisticated hobbyists who take raw images from missions and combine and reprocess them to create stunning new images.

Despite the title, The Art of the Cosmos leans strongly towards art of the solar system: three of the four chapters are devoted to solar system bodies, with the rest of the universe crammed into the final chapter. Bell acknowledges that “bias” in the introduction, noting his background working on planetary missions (including Mars, which may be why that planet gets most of one chapter, sharing it only with asteroids and comets.) That last chapter relies heavily on Hubble images; an interesting choice given there’s a much larger astrophotography community, producing their own fantastic images, than those processing images from spacecraft. That’s not to say the Hubble images aren’t works of art, only that there may be an ever greater variety to consider as well.

The Art of the Cosmos is not a book about the science of the solar system and universe, although Bell does include scientific explanations for the images. It is more of a celebration of the beauty of the cosmos, and a reminder that art and science are not distinct but, rather, intertwined.

| “Stories of space adventurers riding rocket-propelled vehicles into the space frontier became so accepted that no one questioned the various elements of these tales or why those elements fit together.” |

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Thursday, November 24, 2022

Some Beautiful Words From A Russian Lady