Since I was a young child Mars held a special fascination for me. It was so close and yet so faraway. I have never doubted that it once had advanced life and still has remnants of that life now. I am a dedicated member of the Mars Society,Norcal Mars Society National Space Society, Planetary Society, And the SETI Institute. I am a supporter of Explore Mars, Inc. I'm a great admirer of Elon Musk and SpaceX. I have a strong feeling that Space X will send a human to Mars first.

Sunday, January 29, 2023

Saturday, January 28, 2023

Friday, January 27, 2023

Tuesday, January 24, 2023

Why The US Should Make Africa A Priority For Space Diplomacy

Officials from Rwanda and Nigeria sign the Artemis Accords during the US-Africa Leaders Summit in Washington in December. (credit: NASA) |

Mawu and Artemis: Why the United States should make Africa a priority for space diplomacy

by Nico Wood

Monday, January 23, 2023

The Artemis missions represent the most ambitious human spaceflight program in history, demanding international contributions and coordination. As a prerequisite for participation, member countries are obligated to sign the Artemis Accords, a broad-based set of principles and guidelines to advance peace, transparency, and responsibility in space. Representatives from Rwanda and Nigeria signed the Artemis Accords in December 2022, becoming the first African nations to join the international program. The economic, social, and geopolitical potentials of the African continent pose a major opportunity for US space diplomacy, yet the United States has not adequately engaged with African nations. This diplomatic vacuum stems from a general lack of US prioritization of Africa and leaves it open to competition by China and Russia. By pursuing more African nations as partners in the Artemis Accords, the United States can capitalize on Rwanda and Nigeria’s momentum, demonstrate a sustained presence on the continent, and inspire a new generation of Africans through space.

Introduction

In West African myth, Mawu is a goddess who embodies the Moon, often paired with Lisa, the Sun god.[1] Depending on the source, these two entities are known as either separate or as a complementary sexual pair known as Mawu-Lisa. Mawu is known as the most beautiful of the gods and brings cool relief to the punishing heat of the day. Mawu-Lisa was responsible for the creation of the universe by passing through all things inside the mouth of the serpent Aido-Hwedo, who continues to inhabit both the heavens and the Earth and acts both to support the world’s weight and maintain its stability. These myths and the African names for the stars were passed down orally, predating the similar Greek myths of Apollo and Artemis by hundreds of years.[2] When we consider the movers and shakers of space today, we look anywhere but Africa, yet the cradle of humanity still maintains many celestial traditions that demonstrate a deep affinity for the cosmos. In considering additional partners for the Artemis Accords, the United States should recognize the cultural, social, economic, and geopolitical opportunity that Africa presents.

The Artemis Accords

The official mission of the Artemis Accords is “to establish a common vision via a practical set of principles, guidelines, and best practices to enhance the governance of the civil exploration and use of outer space with the intention of advancing the Artemis Program.”[3] NASA’s website features three additional missions: “scientific discovery, economic benefits, and inspiration for a new generation of explorers.”[4] Mike Gold, the former NASA associate administrator for space policy and partnerships, added that the purpose of the Accords was to “create the broadest, most diverse beyond LEO [low Earth orbit] spaceflight coalition in history.”[5] The principles outlined therein include peace, transparency, interoperability, release of scientific data, deconfliction of space activities, and the removal and prevention of orbital debris, among others. Signing the Artemis Accords is a precondition to be involved in the operations of the Artemis Program, which seeks to bring together a diverse, international team to establish the first long-term presence on the Moon.[6]

| By pursuing more African nations as partners in the Artemis Accords, the United States can capitalize on Rwanda and Nigeria’s momentum, demonstrate a sustained presence on the continent, and inspire a new generation of Africans through space. |

With the recent establishment of the Space Force and Artemis Accords, it is clear that the United States views space as a domain worth exploring. The country now has aims to return to the Moon and establish a permanent human presence there.[7] However, the United States cannot do this alone. The difficulty of space exploration is only matched by its cost, and we look to partner countries to help support this burden of expertise and finance. Our greatest partners in these endeavors have been of no surprise; they are the countries with which we share a great cultural and ideological affiliation, and which possess the technological and economic capabilities to contribute to the mission. However, Mike Gold stipulates that the advantage of the Accords, as compared to membership to the International Space Station, is that it is considerably easier to join, and every country, regardless of wealth, education, or resources, can contribute.[8] In discussing possibilities for non-traditional space partners, Gold says, “I do get particularly excited about some of these small countries, and in terms of what they would do, even if it’s as modest as grad students studying some of the lunar imagery or science to help us out, even that, I think would make a huge difference and add to the diversity and vibrancy, sustainability, and ultimately success of the Accords.”[9]

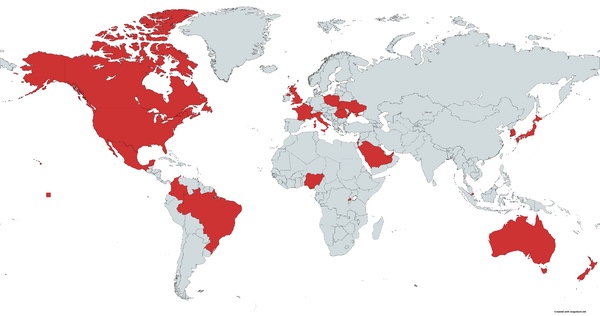

Fig. 1: Signatories to the Artemis Accords as of December 13, 2022.[10] |

On December 13, 2022, Rwanda and Nigeria made history by becoming the first African nations to sign on to the Artemis Accords.[11] The Space Forum was the first event of the US-Africa Leaders Summit, highlighting the impact of space for all.[12] In his opening remarks, Chirag Parikh, executive secretary of the National Space Council, stated that the intent of the forum was to highlight the shared space goals between the United States and Africa and to discuss the use of space in support of sustainable development, capacity building, and the private sector.[13]

Before this event, none of Africa’s 54 countries had signed on to the Artemis Accords, begging the question of why it took until the second anniversary of the Accords for that to happen. There are two possible explanations for this gaping hole in space diplomacy: either the United States had not been interested in or willing to engage with African nations to convince them to sign, or the United States had done so, but African nations were still uninterested or unwilling to sign. One US government official claimed that it was a mix of both but favored the latter.[14] The United States has approached many African nations and demonstrated the importance of signing the Accords. Deputy NASA Administrator Pam Melroy said at a Secure World Foundation event on the Artemis Accords that during meetings with America’s space partners, the US delegation regularly floats the idea of signing the Accords, but did not infer that it is a hard sell.[15]

Afronautics

In 1964, a Zambian schoolteacher named Edward Mukuka Nkoloso made the headlines in Time magazine by launching the first African space program.[16] The nature of his training program (to include rolling students around in an oil drum and teaching them to walk on their hands as they would in space) was derided by the world as at best a publicity stunt and at worst a mentally ill outburst from a backwater former British protectorate. Given the context of Zambia establishing independence, this author believes that the short-lived space program served as a message to the West to take the continent seriously. Nkoloso requested funds from the United States and the Soviet Union to develop the program, but neither superpower saw fit to respond.

More than 50 years after Zambia’s short-lived program, space has become more important than ever for all countries. The leaders of African countries are not naïve; they understand the benefits that the space domain offers, such as telecommunications and remote sensing, and how partnering with major space powers allows them to develop their domestic capabilities more quickly. However, in a patronage system between the United States and China, no African country wants to be seen as affiliating itself too much with one or the other so as not to close any doors in the future. By playing each country off each other, African nations can benefit from both sides and extract maximum perceived value. China’s space diplomacy has been significantly more influential on the continent, resulting in many bilateral agreements and programs to build and launch satellites. That said, the United States still has an opportunity to establish serious dialogue and make inroads with African nations in the field of space. In this section, I will examine several African countries’ motivations for establishing a space program and for cooperating with other countries, with particular emphasis on Rwanda and Nigeria as newly signed partners to the Artemis Accords.

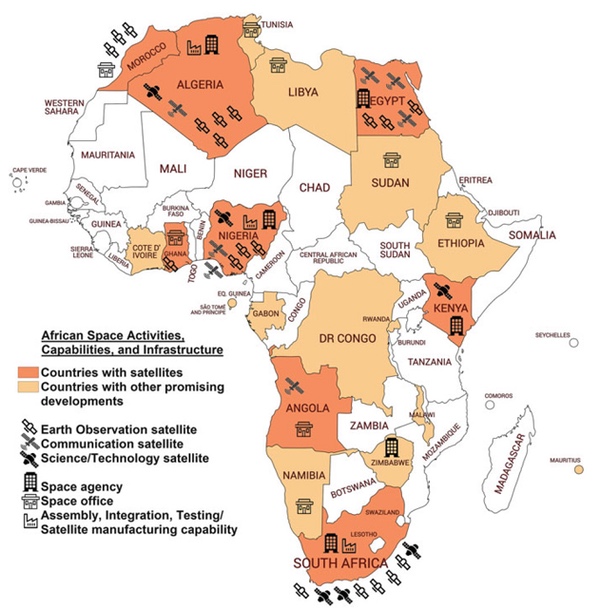

Fig. 2: African Space Activities, Capabilities, and Infrastructure as of 2019[17] |

The African Space Agency (AfSA) was established in 2018 as a constitutive space body between the African Union’s (AU) 55 member states to fulfill the goals of the Africa Agenda 2063.[18] AfSA’s objectives include harnessing the potential benefits of space for addressing Africa’s socio-economic challenges; developing a sustainable, indigenous space market; adopting good corporate practices; and promoting an African-led space agenda through international partnerships.[19] The AU’s space agency cannot be compared to the European Space Agency (ESA), which possesses far greater agency and far more independent authority, though both entities do coordinate among member nations. Some have argued for greater authority to be vested in AfSA so that the continent can act as a united bloc rather than 55 weaker nations.[20] This level of international coordination and trust would likely take years and be unprecedented for Africa, but states may find strategic value in such a project.[21] Without banding together, these relatively emergent space programs could fall prey to the same colonial tactics superpowers used in the past to divide and exploit the continent.

| The leaders of African countries are not naïve; they understand the benefits that the space domain offers, such as telecommunications and remote sensing, and how partnering with major space powers allows them to develop their domestic capabilities more quickly. |

In announcing the country’s signature to the Artemis Accords, Rwandan President Paul Kagame stated that “space-based technology is becoming an increasingly powerful tool for addressing global challenges such as agricultural productivity and climate change.”[22] These needs were the catalyst for the establishment of the Rwandan Space Agency (RSA) in 2020 and the future Space Center of Excellency for Research and Development. The RSA is the coordinating body for all space activities in the country, with goals to promote socioeconomic and industrial development for local and international markets.[23] Satellite communications and remote sensing technologies are two key projects for RSA, and the agency has regularly publicized its interest in participating in the formulation and development of international law and space governance through forums such as the United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA).[24]

Colonel Francis Ngabo, Chief Executive Officer of the RSA, stated that Rwanda joined the Artemis Accords because it “reaffirms Rwanda’s commitment to support peaceful, sustainable, and responsible space exploration. The accords are a reminder of international partnerships as humanity returns to the Moon and the registration of space objects and release of scientific data are some of the accords’ provisions that are in line with our agency’s mandate.”[25] As a unifying rallying cry for developing space powers, President Kagame concluded his speech by saying “As we shoot for the stars, literally and figuratively, let us be sure that exploration of outer space benefits all of… humankind for generations to come.”[26]

In 1999, Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo established the National Space Research and Development Agency (NASRDA) under a new democratic government.[27] Six years later, NASRDA established several extremely ambitious goals: manufacture a satellite, train a Nigerian astronaut, and create a domestic space launch vehicle program.[28] Nigeria has since launched five satellites through cooperation with and funding from both Russia and China. Although met with regular funding issues incongruent with its lofty targets, Nigeria nonetheless possesses one of the most advanced space programs on the continent.

The Nigerian Minister of Communications and Digital Economy, Isa Ali Ibrahim (Pantami), also spoke at the US-Africa Leaders Summit and underlined Nigeria’s space interests in security, agriculture, deforestation, artificial intelligence, and robotics.[29] Indeed, the Director General of NASRDA has stated, “What we need to look at is using the space program to look at how we can create typical Nigerian solutions to most of our problems,” not vanity trips to the Moon and Mars.[30] The country has been able to update its maps, track climate change impacts, and locate members of the terrorist group Boko Haram thanks to the Nigerian satellites in orbit. Minister Ibrahim went on to say that “NASA… is the leading space institution in the world, and any effort to work together will support our country significantly in attaining our vision and also our objectives.” It is clear from his remarks that Nigeria views cooperation with the United States in space as both a practical and prestigious effort. He highlighted the large population of Nigeria and pointed to remote sensing and communications satellites as incredibly important to the country. The country looks to participate in international research and development to improve citizen welfare and capacity building.

Cameroon was the only African country to speak at the US-Africa Leaders Summit Space Forum that did not sign onto the Artemis Accords, and the country lags behind other African nations in terms of space organization, infrastructure, and successes. The country lacks a unified space agency, and although the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications did launch a feasibility studies project on developing a space program called “Camspace,” no news has followed the original statement in 2019.[31]

That said, it is clear that Cameroon does recognize the importance of space. In October 2022, the Cameroonian representative to the United Nations pointed to satellite disaster management and weather forecasting as space-based sources of information which are improving people’s lives.[32] The President of Cameroon, Paul Biya, said in his remarks at the US-Africa Leaders Summit that “right now, even as I speak to you this morning, young Africans and youth around the world are able to watch this talk, and those young people are able to get an idea of what is happening and what is being said thousands of kilometers away. That shows us one of the ways we can use commercial space.”[33] President Biya emphasized the importance of space-enabled communications across the continent and their abilities to advance economic development in Africa. He went on to note that those African countries with satellites do not possess the capability to fulfill all the needs of Africa, and that is why partnering with developed space nations is a necessity. The United States in particular, said Biya, is a leader in space exploration and launching satellites. Remote sensing and data sharing would allow for tracking of the effects of climate change, the development of sustainable urban planning, and the plight of terrorism across the country. However, it is crucial for Cameroon to avoid the militarization of space and he argued for a solely peaceful and noble use of outer space.

Still more African countries have put forward significant resources towards space industry and infrastructure. Ethiopia’s interest in space stems mainly from climate change, economic concerns, and the prestige of joining satellite-operating nations.[34] Ethiopia has focused its two satellites on remote sensing and the Ethiopian Space Science and Technology Institute (ESSTI) on producing technological knowledge and empowering its citizens to take full advantage of the space economy.[35] ESSTI absorbed the Ethiopian Geospatial Information Institute in 2021, indicating a greater unity of effort in the country’s space program. The country’s space budget has rapidly increased since 2018, with a 300% increase between 2019 and 2020.[36]

| China has become a mover and shaker of space norms on the African continent, approaching parity with and in some cases outpacing the United States in the competition for African hearts and minds. |

South Africa is another country worth investigating. The country has broken ground on a deep-space ground station set to come online by 2025, which will support the tracking systems necessary for the Moon to Mars program.[37] The South African National Space Agency (SANSA), established in 2010, will operate and maintain the station and feed information to the Artemis program along with its Australian and US foils. In 2020, SANSA received a R4.4 billion (equivalent to about $250 million) allotment to build a space hub, increasing its previous budget from R150 million (about $8.5 million).[38] Progress on the Space Infrastructure Hub is ongoing, and it will be the construction site for six planned satellites. Given the country’s involvement in the Artemis program as well as its sizeable space capabilities, a source at NASA’s Space Communications and Navigation (SCaN) program says that it is likely South Africa will sign the Artemis Accords soon.[39]

Brian Weeden, Director of Program Planning for Secure World Foundation, said that developing space countries like those in Africa “are looking at this differently. They are looking for different things, not just to go to the Moon or something, but also benefits on Earth.”[40] Given the tremendous costs of space, many emerging space powers rely on major space powers to launch or service their satellites rather than indigenously create the entire infrastructure. Human spaceflight seems relatively pie in the sky for Africa, and to date, only one “afronaut” exists.[41] From the comments of heads of African governments and space agencies, we can see that the main space concerns for these many African countries are tangible benefits on Earth. African space agencies and policymakers cite core themes, such as economic and socio-economic development, public-private coordination, geopolitical prestige and security, and regulatory and legal influence.[42]

Red teaming

China has become a mover and shaker of space norms on the African continent, approaching parity with and in some cases outpacing the United States in the competition for African hearts and minds. The most recent white paper from Beijing starts by quoting Xi Jinping: “To explore the vast cosmos, develop the space industry and build China into a space power is our eternal dream,” and space is a critical component of national strategy.[43] The paper goes on to state China’s intent to formulate a “law-based” system of space industry governance based on Chinese research. China’s voluntary cash contributions to UNOOSA in 2020 far outpaced any other single country, and Beijing’s footprint as a Security Council member continues to grow.[44] China’s response to United Nations Resolution 75/36, Reducing space threats through norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviours, paints the United States and the United Kingdom as warmongers in space and warns against weaponizing the environment.[45] Given China’s interest in becoming the world’s premier leader in space and the United States’ perceived great power competition with the country, many are calling this the new “space race.” The Biden administration has made it a priority to “boldly engage the world” amidst a growing rivalry with China—space diplomacy in Africa may seem like a small step, but it could become a giant leap in the great power competition with China.[46]

Given a lack of American space diplomacy in the continent, Africa has looked to the East for guidance. China’s taikonauts aboard the Chinese Space Station recently spoke virtually to citizens of the member states of the African Union (AU), answering questions from young people interested in space.[47] This approach has been remarkably successful in inspiring the next generation of Africans who see China as a means to enter into the club of spacefaring nations. Additionally, China seeks to expand political influence in space partner countries like Ethiopia, Algeria, Tunisia, and Egypt to compete with the United States.[48] China recognizes the power of the podium and seeks to have its phrases echoed inside and outside the country. The verbiage from Cameroonian President Biya with regards to avoiding the militarization of space is close to the language used by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).[49] While this does not mean that Cameroon is in the CCP’s pocket by any means, it may indicate a reluctance to sign on to the Accords and risk rupturing their relationship with China.

The Chinese Ambassador to the AU, Hu Changchun, remarked, “In recent years, driven by the Belt and Road Initiative and the China-Africa Cooperation Forum, space cooperation has become a strong point in promoting our comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership. The diversified exchanges have yielded abundant fruits, especially in the manufacture and launch of satellites, the construction of aerospace infrastructure, the sharing of satellite resources, the training of engineers and joint research.”[50] After working with China for years on pragmatic satellite projects, Nigeria’s NASRDA sent a delegation to Beijing to discuss the possibility of training a Nigerian astronaut and sending them to space.[51]

There are clear economic incentives for China to develop space relations with African countries: the African space economy was valued at over $19 billion in 2022, and experts believe it could grow to $22 billion by 2026.[52] While this timeline may be overly ambitious considering the country’s current capabilities in space, leaders claim that the vision is more important than the execution, and China is delighted to create inroads into the biggest economy in Africa through space.

| From many African perspectives, the Artemis Accords seem inextricably linked with the United States framework despite NASA’s insistence that it is a multilateral agreement. |

Ethiopia’s success in space, for example, has come thanks to cooperation with China. Ethiopia’s first foray into space was researched, constructed, and launched almost entirely by Beijing.[53] China took on $6 million of the $8 million total cost to construct and launch the Ethiopian Remote Sensing Satellite-1. Only a year later, Ethiopia launched a second satellite thanks to Chinese patronage.[54] This nanosatellite was to provide an even clearer picture and resolution and relied heavily on research and development collaboration with China. The Director of the China National Space Administration and the Ethiopian Minister of Innovation and Technology signed a bilateral agreement for space cooperation that same year.[55] The two nations have agreed to collaborate on a future communications satellite, but this will be built in Ethiopia, perhaps indicating a greater level of independence and domestic control.[56]

From many African perspectives, the Artemis Accords seem inextricably linked with the United States framework despite NASA’s insistence that it is a multilateral agreement. By reframing the nature of the Accords through strategic public affairs and increased financial and operational contributions by non-US members, African countries may have an easier time signing on and avoiding future Chinese cuts to development projects. Top-level discussions between heads of government convinced France’s government to sign the Accords in June 2022—were the Biden administration to continue making the Accords a priority for African nations, the Accords would likely see a spike in signatories.[57] While it is extremely unlikely given the current political environment, having China sign the Accords would also potentially inspire many non-aligned countries to follow suit.

Opportunity isn’t just a rover on Mars

Africa is the demographically youngest continent with the fastest growing population and economy in the world.[58] The United States has so far failed to recognize this and implement a geopolitical and economic strategy to capitalize on Africa’s potential. In the most recent version of the National Security Strategy (NSS), the Biden administration organizes Africa on page 43, just after the Middle East but before the Arctic.[59] This sets the United States up to cede the continent to outside influence. The main goals outlined in the NSS are reversing democratic backsliding, countering terrorist activities, and combating economic, food, and human insecurities. There is no mention of space activities with Africa, though incorporating satellites into climate change and counterterrorism solutions is not too far a stretch. As with any form of diplomacy, space diplomacy requires sustained, vigorous engagement. However, the United States tends to spend its limited political capital in Africa on security and aid.

NASA Administrator Bill Nelson spoke at the US-Africa Leaders Summit and noted the importance of space partnerships with Africa, in particular deforestation, communications, and improving people’s lives.[60] He emphasized the rule of law in separating those countries that prosper from those which do not, then spoke of NASA’s collaboration with the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in supporting sustainable development and emergency relief in developing nations. He summarized the Artemis Accords as “a commonsense statement of principles of what we should do peacefully in space,” involving mutual aid, standardization, and transparency. Invoking President Kennedy, Nelson stated that space is hard, but it is how we can come together as peoples.

Monica Medina, the Assistant Secretary of State for Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs (OES), began her speech at the US-Africa Leaders Summit by saying that the first images revealing the devastation of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 did not come from an American satellite, but a Nigerian satellite.[61] This, she continued, demonstrated the impact of space partnerships, and space has become the backbone for economic development and scientific cooperation. Assistant Secretary Medina highlighted the diversity and peaceful nature of the Artemis Accords as well as the US commitment to the anti-satellite moratorium. The United States, in support of shared early warning systems for all, seeks to communicate data to reveal information about the climate challenge ahead of us. She continued by saying that the now $469 billion space economy can act as an economic driver towards development. Medina concluded by hoping that Rwanda and Nigeria’s signatures provide momentum towards other African nations signing on to the Accords.

As mentioned in Assistant Secretary Medina’s remarks, Africa also offers significant scientific opportunity for the future of space exploration. By sharing remote sensing data internationally, African nations can contribute to the fight against climate change; this information could prompt leaders to take deforestation and overgrazing seriously and reverse harmful policies. Astronaut training or long-term habitation programs could take advantage of much of the Sahara Desert’s Mars-like environment. The Danakil Depression in Ethiopia is one of the most alien and unique environments on Earth and continues to inform scientists on how extremophilic life could survive in such harsh, acidic conditions.[62] Equatorial spaceports facilitate the launching of objects into space, and Africa is home to the majority of landmass surrounding the equator. In fact, Kenya is home to the Luigi Broglio space center, an offshore launch facility formerly owned and operated by Italy.[63] The facility has not been used for launches since 1988 and has since become Kenyan property. By refurbishing the Broglio space center and establishing others, Africa could have a potential comparative advantage to many other space launch facilities around the world.

99 problems but Algiers ain’t one

The most cogent counterargument to this paper stems from the fact that there is little US political interest in Africa, represented in a relatively meager budget stretched across security and aid.[64] In the 2021 posture statement to the US Congress, the United States Africa Command (USAFRICOM) claimed just 0.3% of the total Department of Defense budget and manpower.[65] With so many competing interests, why should the United States focus on Africa? Is our money not better spent on other projects and our political capital not better spent on immediate concerns? Also, what tangible benefits does the United States actually receive out of this arrangement?

| Investing increased political and economic capital in Africa may not appear like a priority to the White House, but it is the best way to position the United States for a future in which Africa’s influence has grown dramatically. |

In the era of globalization, policymakers must be tapped into every part of the world, since a merger of two Asian countries could affect the New York Stock Exchange and an insurgency in Africa could direct military funding in Europe. By hyperfixating on what appear to be the biggest challenges of today, we grow myopic and neglect the challenges of tomorrow. This is the essence of strategic forecasting: the process creates alternative futures and crucial junctures to help policymakers understand where relative advantages and vulnerabilities lie.

Investing increased political and economic capital in Africa may not appear like a priority to the White House, but it is the best way to position the United States for a future in which Africa’s influence has grown dramatically. Furthermore, many African nations are at a nascent phase of space development, with most not having established a centralized space program. By involving these nations early in the process, the United States can share standardized practices and norms to promote interoperability and open communication. This is not to say we should pivot from a great power competition strategy with China and Russia towards a minor power cooperation strategy with Africa, but that African nations will bear the greatest returns on investment in terms of space diplomacy. By understanding what Africa needs out of space and working with leaders to make small steps, a small adjustment in US foreign expenditures could make a world of difference.

The Mawu-Lisa Accords

In conclusion, the goals of the Artemis include establishing unifying international principles in civil space in the pursuit of science, economic benefits, and inspiration for the next generation. The Accords seek diversity of thought, nationality, and ethnicity. Africa represents untapped potential in achieving these goals, and the United States should not be satisfied with the recent signing of Rwanda and Nigeria but rather capitalize on the momentum to attract new signatories from the continent. Countries that have already engaged with the United States on space projects such as South Africa make for the likeliest targets. This will require renewed interest in Africa and an increased, sustainable budget to dedicate long-term diplomatic efforts. By involving African nations early on, the United States can demonstrate its commitment for multilateral direction of the Accords and rebuff the narrative of American space hegemony. The economic, security, and science incentives to partner with African nations on the Artemis Accords are compounded by the fact that if the United States fails to do so, China happily will. Thousands of years ago, humankind looked up to the stars and created stories that were bigger than ourselves. These myths inspired us to unite and discover what else was out there. The United States should work with African nations to sign on to the Artemis Accords and create an opportunity for generations to come to be united and inspired once again.

Endnotes

- Melville J. Herskovits, Dahomey: An Ancient West African Kingdom (Delhi: Delhi University, 1938).

- Jim Beckerman, “New documentary to show centuries before the Greeks, African astronomers named the stars,” NorthJersey, September 24, 2021.

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration, The Artemis Accords: Principles for Cooperation in the Civil Exploration and Use of the Moon, Mars, Comets, and Asteroids for Peaceful Purposes (Washington, DC: NASA, 2020), 2.

- “Artemis,” National Aeronautics and Space Administration, accessed December 14, 2022.

- Mike Gold, “Secure World Foundation’s ‘Artemis Accords: Past, Present, and Future’ Event” (panel discussion, Washington, DC, December 12, 2022).

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration, “Artemis,” accessed December 14, 2022.

- Ibid.

- Mike Gold, “Secure World Foundation’s ‘Artemis Accords: Past, Present, and Future’ Event” (panel discussion, Washington, DC, December 12, 2022).

- Ibid.

- Author creation. Color should be used to indicate signatory countries.

- The White House, “STATEMENT: Strengthening the U.S.-Africa Partnership in Space,” December 13, 2022.

- U.S. Department of State, “U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit,” accessed December 13, 2022.

- U.S. Department of State Summits and Conferences, “U.S. Africa Leaders Summit - Day 1 - Stream 2 [EN],” YouTube, December 13, 2022, international summit, 0:00 to 1:18:33.

- This conclusion comes from a private interview with a USG official speaking under non-attribution.

- Pam Melroy, “Secure World Foundation’s ‘Artemis Accords: Past, Present, and Future’ Event” (speech, Washington, DC, December 12, 2022).

- Namwali Serpell, “The Zambian Afronaut who Wanted to Join the Space Race,” The New Yorker, March 11, 2017.

- Annette Froehlich and André Siebrits, Space Supporting Africa, vol. 1, A Primary Needs Approach and Africa’s Emerging Space Middle Powers (New York: Springer, 2019).

- African Union, “Statute of the African Space Agency,” 2; and African Union, “1st African Space Week,” accessed December 14, 2022.

- African Union, “Statute of the African Space Agency,” 3.

- Memme Onwudiwe, “Africa and the Artemis Accords: A Review of Space Regulations and Strategy for African Capacity Building in the New Space Economy,” New Space 9 no. 1 (March 19, 2021).

- Kasibante David, “The Artemis Accords: Opportunities for the African Space Industry,” Space Generation Advisory Council, accessed December 15, 2022.

- U.S. Department of State Summits and Conferences, “U.S. Africa Leaders Summit - Day 1 - Stream 2 [EN],” YouTube, December 13, 2022, international summit, 0:00 to 1:18:33.

- “About Rwanda Space Agency,” Rwanda Space Agency, accessed December 14, 2022.

- @RwandaSpace (Rwanda Space Agency), “@RwandaSpace team participating at the @UNOOSA Technical Advisory Mission "space law for new actors" in Vienna shared on #Rwanda's journey with other African space actors. Intl. Cooperation and contribution to governance of outer space are among @RwandaSpace's key objectives,” Twitter, December 6, 2022.

- @RwandaSpace, “Historic Moment: #Rwanda becomes the first African country to sign the #Artemis Accords. Press release,” Twitter, December 14, 2022.

- U.S. Department of State Summits and Conferences, “U.S. Africa Leaders Summit - Day 1 - Stream 2 [EN],” YouTube, December 13, 2022, international summit, 0:00 to 1:18:33.

- Tyler Way, “Challenges and Opportunities of Nigeria’s Space Program,” CSIS, June 24, 2020.

- Francis Chizea, “Space Technology Development in Nigeria,” NASRDA, December, 2017.

- U.S. Department of State Summits and Conferences, “U.S. Africa Leaders Summit - Day 1 - Stream 2 [EN],” YouTube, December 13, 2022, international summit, 0:00 to 1:18:33.

- Eleni Giokos and Logan Whiteside, “Nigeria: Our space program is not an ‘ego trip,’” CNN Money, June 7, 2016.

- “Cameroon Plans to Launch a National Space Programme,” Space in Africa, August 26, 2019.

- United Nations General Assembly, “Delegates Spotlight Ways That Space Technology Can Help Reach Global Goals as Fourth Committee Continues Examining Peaceful Uses of Space,” October 28, 2022 (77th session, 16th meeting).

- U.S. Department of State Summits and Conferences, “U.S. Africa Leaders Summit - Day 1 - Stream 2 [EN],” YouTube, December 13, 2022, international summit, 0:00 to 1:18:33.

- “Ethiopia hails Chinese-backed satellite launch,” Xinhua, December 22, 2019.

- “About Us,” Ethiopian Space Science and Technology Institute, accessed December 14, 2022, ; and “Ethiopian Space Program,” Ethiopian Space Science and Technology Institute, accessed December 14, 2022, presentation.

- “To give you some context: Ethiopia’s Space Program,” Business Info Ethiopia, December 30, 2021.

- Wendell Roelf, “South Africa’s new ground station to help track space flights,” Reuters, November 9, 2022.

- Sarah Wild, “SA’s new R4.5bn space hub will build up to 6 new satellites - here's what you need to know,” Business Insider, August 27, 2020.

- Information taken from a NASA SCaN source.

- Brian Weeden, “Secure World Foundation’s ‘Artemis Accords: Past, Present, and Future’ Event” (panel discussion, Washington, DC, December 12, 2022).

- Samra Ahmed, “Sara Sabry Becomes the First Egyptian to Go to Space in a Blue Origin Flight,” Vogue, August 5, 2022.

- Rose Roshier, “Recommendations for US-Africa Space Cooperation and Development,” Center for Global Development, March 2022, 1-2.

- China National Space Administration, “China’s Space Program: A 2021 Perspective,” The State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China, January 2022.

- “Annual Report 2020,” United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs, June 2021, 91.

- People’s Republic of China, “Document of the People’s Republic of China pursuant to UNGA Resolution 75/36 (2020),” United Nations General Assembly, accessed December 14, 2022.

- The White House, “Interim National Security Strategic Guidance,” 6.

- Kate Bartlett, “Why China, African Nations are Cooperating in Space,” Voice of America, September 13, 2022.

- Jevans Nyabiage, “China aims to lift Africa’s space ambitions in drive to beat US domination,” South China Morning Post, September 8, 2022.

- People’s Republic of China, “Document of the People’s Republic of China pursuant to UNGA Resolution 75/36 (2020),” United Nations General Assembly, accessed December 14, 2022, 3-4.

- “China-Africa Space Cooperation: A New-Era of Co-Development and Co-Prosprosperity [sic],” SinAfrica News, September 8, 2022.

- Kieron Monks, “Nigeria plans to send an astronaut to space by 2030,” CNN, April 6, 2016.

- Maingi Gichuku, “African Space and Satellite Industry now valued at USD 19.49 Billion,” The Exchange, August 23, 2022.

- Elias Meseret, “Ethiopia’s first satellite launched into space by China,” Associated Press, December 20, 2019.

- “Ethiopia launches second Chinese-backed satellite: Official,” Xinhua, December 24, 2020.

- China National Space Administration, “China’s Space Program: A 2021 Perspective,” The State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China, January 2022.

- “To give you some context: Ethiopia’s Space Program,” Business Info Ethiopia, December 30, 2021.

- Jeff Foust, “France joins Artemis Accords,” SpaceNews, June 8, 2022.

- Prashant Yadav and Vinika D. Rao, “How Africa Could Astonish the World,” INSEAD, June 29, 2021.

- The White House, “National Security Strategy,” October 12, 2022, 43.

- U.S. Department of State Summits and Conferences, “U.S. Africa Leaders Summit - Day 1 - Stream 2 [EN],” YouTube, December 13, 2022, international summit, 0:00 to 1:18:33.

- U.S. Department of State Summits and Conferences, “U.S. Africa Leaders Summit - Day 1 - Stream 2 [EN],” YouTube, December 13, 2022, international summit, 0:00 to 1:18:33.

- Jodie Belilla et al., “Exploring microbial life in the multi-extreme environment of Dallol, Ethiopia,” Geologic and Mineral Institute of Spain (2017).

- “The ‘Luigi Broglio’ space center in Malindi, Kenya,” Agenzia Spaziale Italiana, accessed December 15, 2022.

- Tomas F. Husted et al., “U.S. Assistance for Sub-Saharan Africa: An Overview,” Congressional Research Service, August 30, 2022.

- Gen. Stephen Townsend, “Africa: Securing U.S. Interests, Preserving Strategic Options,” excerpt from testimony to the House Armed Services Committee, United States Africa Command, April 20, 2021.

Nico Wood is a second year Master of Science in Foreign Service candidate in the Science, Technology, and International Affairs concentration at Georgetown University. He is also a Graduate Intern at the Aerospace Corporation’s Center for Space Policy and Strategy (CSPS). Additionally, Mr. Wood has continued to serve in the Air Force Reserve since separating from active duty in 2021.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

What The United States Should Do Concerning Space Leadership?

What the United States should do regarding space leadership?

by Namrata Goswami

Monday, January 23, 2023

The domain of space is changing fast. Once the realm of elite astronauts and space scientists who had access based on state sponsorship or university-funded programs, today space is truly democratizing, being adopted by almost anyone with a passion and an inclination to do space, creating companies, networks, and investing in the development of space. Look no further than countries like India or Japan, long dominated by elite state-sponsored space institutions but now creating enabling structures, be it in regard to new organizations, regulations, and investment opportunities for private citizens to develop space capacities and collectively take their societies forward.

| Cold War-dictated concepts like technology demonstration and prestige missions to showcase ideological superiority, funded by billions of dollars of taxpayer money, cannot sustain space investments in this changing world. |

One look at Japan’s basic space law and policy of 2008 shows that the language used about space is focused on space development and utilization, specifically as it aims to develop Japanese citizens’ capacity to earn economic returns from Japan’s space development. For Japan, it states, “Space Development and Use shall be carried out in order to strengthen the technical capabilities and international competitiveness of the space industry and other industries of Japan, thereby contributing to the advancement of the industries of Japan, by the positive and systematic promotion of Space Development and Use as well as smooth privatization of the results of the research and development with regard to Space Development and Use.” Japan pointed out that cooperation with the United States is critical in this regard.

This is in an interesting shift in language and narrative, as the space economy grows and becomes an integral part of an individual, and by extension, a community’s life. Cold War-dictated concepts like technology demonstration and prestige missions to showcase ideological superiority, funded by billions of dollars of taxpayer money, cannot sustain space investments in this changing world. A country has to justify their space missions based on economic return. We witnessed this reality when the Indian Minister of State (Independent Charge) for Science and Technology and Earth Sciences, Jitendra Singh, had to rationalize money spent on India’s human spaceflight program as aimed at building space tourism, specifically by promoting the participation of the private space sector through the Indian National Space Promotion and Authorization (IN-SPACe) agency. IN-SPACe is a new agency established under the Indian Department of Space to promote and authorize the Indian private sector activities in space. A country like China, known for the dominance of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in regard to its space programs, issued direction in 2014 for the development of China’s private space sector—of course, in tight coordination with its state-sponsored civilian space and military institutions—to develop space capacities like reusable rockets, satellite constellations, and commercial spaceports.

In this context of a fast-changing space environment, assuming global leadership in space through establishing norms and standards of behavior—a rules-based regime in space—by a group of democratic nations, is vital. The US remains, by far, the leading nation in space but that lead is fast shrinking with China’s emergence as a spacepower in the 21st century, enhanced with the strategic partnership that China has established with Russia. China under President Xi Jinping has articulated grand strategic ambitions of assuming leadership in key strategic technologies, including space.

| The framework misses the boat on where partner nations want to go: space development and use, space tourism, and space as an industrial activity. |

Wu Yansheng, Chairman of China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC), outlined China’s ambitions in space in an interview on China Central Television-CCTV December 20. Those ambitions follow a strategic plan of the CPC to turn China into a comprehensive spacepower in the next two decades Writing the rules of the road, determining the space economy and space governance mechanisms, and underwriting the space development of other nations through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Spatial Information Corridor are key components of China’s plans for space development and space utilization.

US Space Priorities Framework

Under the Biden Administration, the US released its Space Priorities Framework in December 2021 that focused on how space activities enhance our lives by offering satellite communications, data, help address the climate crisis, and how “space exploration and scientific discovery attracts people from across America and around the world to engage in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).” Space was projected as a mystery in the document that exploration missions will help unlock, and that “the United States will maintain its leadership in space exploration and space science.” The Priorities Framework indicated that “the United States will advance the development and use of space-based Earth observation capabilities that support action on climate change”. Regulations that the Biden Administration aspires to promote are those that enable a commercial space sector focused on traditional space goals like space applications and space-enabled services.

All these are laudable space goals, but the framework misses the boat on where partner nations want to go: space development and use, space tourism, and space as an industrial activity. Japan just licensed the first business activity on the Moon when it granted the first space mining license to ispace supported by its space mining legislation that also establishes ownership of those resources. Consequently, US partner nations are taking leadership and organizing to deal with challenges like China. For example, Japan took the initiative towards creating frameworks like the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue that includes space cooperation among Japan, the US, Australia, and India.

While the US Space Priorities Framework is a good document and touches upon all the usual issues like space science, space exploration, space leadership, and does recognize space as part of US critical infrastructure (if not critical infrastructure itself), it completely fails to recognize the changing global landscape of the space narrative focused on space development and utilization. The document asserts US space leadership while failing to provide how that leadership is being developed in the 21st century and is unclear as to which key space domains and technologies (low Earth orbit, cislunar space, in-space manufacturing, renewable energy, etc.) are the key focus of the Biden Administration. The document does not provide strong enough strategic rationales for why other nations should accept this US leadership in space at all, and why it is important for the US to maintain that leadership in a world where authoritarianism is on the rise.

What should the US do, then, to maintain space leadership and ensure that the future in space is democratic, inclusive, and representative, and is indeed enabling democratic societies to commercially benefit from space development and utilization?

Recommendations for US actions

It is critical that the United States charts a policy direction in space that recognizes this critical component of space development and space utilization for communications, commerce, trade, navigation, military capability, space resource utilization, and business activity in cislunar space. What the United States particularly needs to accomplish is to ensure that this leadership position in space that the Cold War offered the United States remains a key strategic advantage in the 21st century.

For this key strategic advantage to continue, the United States needs to ensure five vital things in space.

| The US space vision should offer a compelling vision of the economic development of space that other nations and their societies can relate to. |

First, the US should recognize and connect space development and space utilization to its grand strategic vision of who it is in the 21st century, especially after the end of the Cold War, particularly to promote democratic development of space, and for free commerce to flourish. This implies that a 21st century US space priorities framework, instead of starting with the most obvious goals of “leadership in space exploration and space science,” should instead state that the United States will maintain leadership in space to enable the democratic development of space, and that it will accomplish these with like-minded partner nations. Such democratic space developments will include harnessing renewable energy in space like space-based solar power (SBSP) that will help tackle climate change, development of the Moon as an industrial hub enabled by responsible regulation, and the use of space for national security purposes to ensure access to space remains free and open.

Second, while Earth observation capabilities are critical means to the end of understanding Earth and preserving our planet, they are not an Apollo-like mission that galvanized an entire generation. Unfortunately, the Artemis lunar mission is not Apollo either, and in its current form not aimed at long-term development of the Moon for economic purposes. China’s Chang’e missions, with long-term goals of permanent settlement of the Moon and the utilization of space resources like helium-3 and water ice is galvanizing the Chinese population to support China’s space development and is drawing in members of the BRI. The US needs to make the Artemis program not only more sustainable in the long run but also have bolder visions of lunar development that follows Japan’s cutting-edge space innovations in mining regulation and space policy.

Leadership in cislunar space is key in setting the right narrative for democratic development of space, and not just limited to Earth orbits like LEO and GEO. The Moon is the focus of spacefaring nations and societies across the world. The US needs to set the right narrative and the vision that others can be inspired by, and that vision for lunar development should spur a movement for responsible development of the Moon. The US does not have such a narrative yet, but should build one that is suitable for 21st century space. Human beings are moved by grand visions that they can relate to and feel included in. The time is ripe for such a US grand strategic narrative for space. Perhaps President Biden can offer such a vision of space development.

Third, committing resources to space development is extremely important. By resources, I mean stable long-term financing and joint ventures, such as, for example, a joint venture between the US and Japan or other members of the Quad on SBSP or lunar development for resource utilization. That would be a gamechanger, something innovative and inspiring. If successful, it will have the potential to change the world energy situation. At a minimum, it will galvanize innovation, jobs, and scientific spinoffs that space has provided for so many other industries in our lifetime. Such funding commitments can only happen with a clear space vision of development and utilization.

Fourth, the US should commit to truly democratize space, moving the space discourse from elites to larger societies across the world, something like what has happened with the Internet, which evolved from a small network for researchers funded by the Defense Department in 1969. A similar trajectory can be charted in space, as we shift space travel from an elite activity today with only few of us fortunate enough to be state-chosen astronauts or with millions of dollars to afford a seat to get to space—to the point that we idolize the few astronauts today—to enabling millions of us to access space and turning space into a normal activity. If US leadership in space can accomplish such a feat, that will be a true inspiration to humanity.

Finally, space is economic power. China recognizes that, Japan recognizes that, and so do several other nations. From the Chinese grand strategic perspective, a nation can only build its influence if it emerges as the top economic power. Once that is accomplished, military power and diplomatic power is going to follow. Space is perceived and sold as building China’s economic power. What is important to realize is that even China’s lunar program is marketed as an investment program that could bring about $10 trillion annually within the framework of an Earth-Moon Economic Zone by 2050.

The US continues to perceive space as a prestige issue, projecting future achievements like landing humans again on the Moon as grand achievements similar to Cold War narratives while the rest of the world has moved on from “space as prestige” to “space as economic and military power.” Grand visions are critical to garner long-term support, both from domestic constituencies but also from the world at large. The US space vision should offer a compelling vision of the economic development of space that other nations and their societies can relate to. Such grand visions worked during the Cold War, in weaving together the idea of free societies versus the Soviet Union model of controlled societies. It is therefore important from a grand strategic perspective that the US, with its multiethnic, multicultural society (despite its difficulties), truly symbolizes democratic representation and freedom, and is therefore the best option we have to lead the future space international order.

In conclusion, the United States should take leadership and develop a clear vision of space development and use. Only such a grand strategic visioning will galvanize society and create an enormous inspirational conversation about what the United States can do for humanity in space.

Namrata Goswami, Ph.D. is an independent scholar on space policy and great power politics and co-author of the book Scramble for the Skies The Great Power Competition to Control the Resources of Outer Space.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Skylab Astronauts Took Pictures Of Area 51 (Groom Lake)!

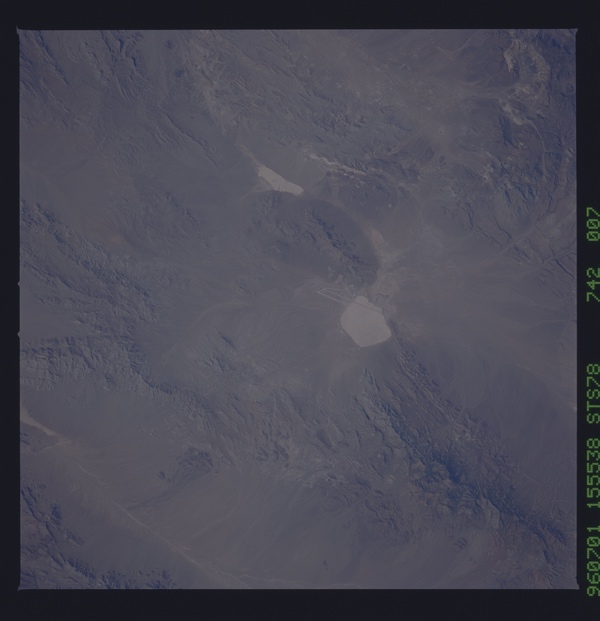

This photo of the secretive Groom Lake facility in the Nevada desert was taken by the Skylab 4 astronauts—who were instructed to not photograph the facility. Its existence created a stir within the US Intelligence Community in 1974. (credit: NASA) |

Not-so ancient astronauts and Area 51: the Skylab Incident

by Dwayne A. Day

Monday, January 23, 2023

[Editor’s Note: This is an extensively revised and updated version of “Astronauts and Area 51: the Skylab Incident” from January 9, 2006.]

On April 19, 1974, someone in the CIA sent the Director of Central Intelligence, William Colby, a memorandum regarding a little problem.

“The issue arises from the fact that the recent Skylab mission inadvertently photographed” the airfield at Groom Lake. “There were specific instructions not to do this,” the memo stated, and Groom “was the only location which had such an instruction.”

| The CIA considered no other spot on Earth to be as sensitive as Groom Lake, and NASA astronauts had just taken a picture of it. |

Groom Lake isn’t really a lake. Or at least it’s not usually a lake. It is a dry lakebed, far out in the Nevada desert, miles from prying eyes. It is a secret Air Force facility that has been known by numerous names over the years. It has been called Paradise Ranch, Watertown Strip, Area 51, Dreamland… and Groom Lake. Groom is probably the most mythologized real location that few people have ever seen. For people with overactive imaginations, it is where the United States government keeps dead aliens, clones them, and reverse-engineers their spacecraft. It is also where NASA filmed the faked Moon landings. So Groom Lake is not only not usually a lake, it is for many people a magical location, a Shangri La in the Nevada wastelands.

However, for humans whose feet rest on firmer ground, Groom is the site of highly secret aircraft development. It is where the U-2 spyplane, the Mach 3 Blackbird, and the F-117 stealth fighter were all developed and/or tested. It has also probably hosted its own fleet of captured, stolen, or clandestinely acquired Soviet and Russian aircraft. Because of this, the United States government has gone to extraordinary lengths to preserve the area’s secrecy and to prevent people from seeing it.

The CIA considered no other spot on Earth to be as sensitive as Groom Lake, and NASA astronauts had just taken a picture of it.

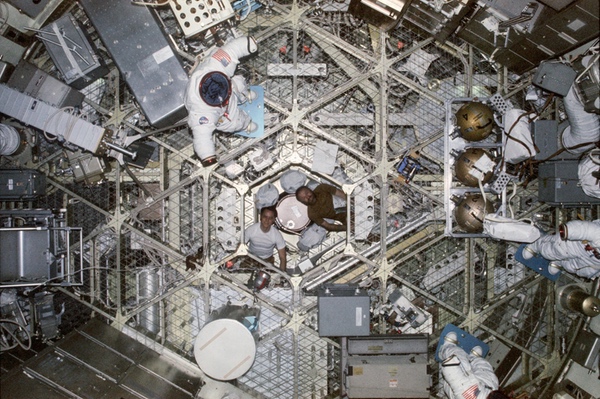

The Skylab 4 crew was the third and last crew to visit the orbiting space station. (credit: NASA) |

Shutterbugs

The third and last Skylab crew had launched into space on November 16, 1973, as part of the Skylab 4 mission. Onboard were three rookie astronauts: Gerald Carr, Edward Gibson, and William Pogue. Carr was a Navy commander, Pogue was in the Air Force and had flown for their elite Thunderbirds team, and Gibson was a scientist-astronaut with a doctorate in engineering physics.

The crew quickly fell behind schedule early in their mission for several reasons, but soon regained time. They repaired an antenna, fixed problems with the Apollo Telescope Mount and an errant gyroscope, and replenished supplies. They accumulated significant EVA time and studied the sun for over 338 hours.

The three astronauts of Skylab 4 were Gerald P. Carr, Edward G. Gibson, and William R. Pogue. Their mission lasted 84 days. (credit: NASA) |

They also took photographs of the Earth, including a photo of the secretive Groom Lake facility in Nevada. On February 4, 1974, after a record 84 days in space, they splashed down 280 kilometers southwest of San Diego. They were recovered aboard the USS New Orleans and found to be in excellent shape.

NASA had an agreement with the US intelligence community that dated from the beginning of the Gemini program: All astronaut photographs of the Earth would first be reviewed by the National Photographic Interpretation Center in Building 213 in the Washington, DC Navy Yard. NPIC (pronounced “en-pick”) was an organization managed by the CIA that interpreted satellite and aerial photography. At first, the photo-interpreters had wanted to see what astronauts could contribute to reconnaissance photography. During the Gemini program they discovered the answer: not much. The photographs returned during the Gemini missions had many problems, including lack of data on what the camera was pointed at. There was no good way for an astronaut to record the precise time and pointing angle of a camera when he took a picture, and so the interpreters often had a very difficult time determining what they were looking at.

But there was another reason to evaluate the astronaut photographs: to see if they showed anything interesting, or anything that they should not, like a top-secret airstrip in the middle of nowhere.

Spooky actions at a distance

There was a certain irony in NPIC photo-interpreters discovering photographs of Groom Lake, because even within NPIC’s highly-secure Building 213, Groom Lake was classified. Images of Groom were removed from rolls of spy satellite film and stored in a restrictive vault. As a former senior NPIC official explained, “there were a lot more things going on at Groom than the U-2.” Not all the photo-interpreters at NPIC were cleared to know about these things, but they included aircraft testing of advanced reconnaissance drones and captured Soviet fighter planes. The average photo-interpreter might know that the U-2 and the Blackbird had been tested at Groom, but would be surprised to see a B-52 with drones, or a MiG-21 sitting on its runway. Soviet MiGs were evaluated and flown at Area 51 starting in the late 1960s, and it is possible that they were present at the base when the Skylab astronauts took their photo.

| Why the Skylab 4 astronauts disobeyed their orders and took the photo is unknown. |

In fact, in April 1962 a CIA official suggested to his superior that they consider taking pictures of Area 51 using their own reconnaissance platforms. John McMahon, the executive officer of the abstractly named Development Plans Division, wrote the acting chief of DPD: “John Parangosky and I have previously discussed the advisability of having a U-2 take photographs of Area 51 and, without advising the photographic interpreters of what the target is, ask them to determine what type of activity is being conducted at the site photographed.” He continued: “In connection with the upcoming CORONA shots, it might be advisable to cut in a pass crossing the Nevada Test Site to see what we ourselves could learn from satellite reconnaissance of the Area. This coupled with coverage from the Deuce [U-2] and subsequent photographic interpretation would give us a fair idea of what deductions and conclusions could be made by the Soviets should Sputnik 13 have a reconnaissance capability.”

Whether or not CIA ever undertook such an exercise remains unknown, but CORONA spacecraft did photograph Area 51 at least a handful of times, so there was opportunity to do such an analysis.

At the time the Skylab photo was being debated within the US government, intelligence officials were apparently unaware that a US Geological Survey photo of Groom Lake had been taken in 1968 and was publicly available, although not public. (credit: USGS) |

The controversy

Why the Skylab 4 astronauts disobeyed their orders and took the photo is unknown. Because they had only handheld cameras for earth observation, the resolution of the image was low. The existence of the base was not a secret, particularly to an Air Force pilot like Bill Pogue—the pilots who flew in the huge Nellis testing range in Nevada referred to Area 51 as “the box” because they were under explicit instructions to not fly into that airspace. But for whatever reason, they had taken the photo and now it had created a stir within the intelligence community.

The April 1974 CIA memo explained the current dilemma government officials were facing over the Skylab crew’s action: “This photo has been going through an interagency reviewing process aimed at a decision on how it should be handled,” the unnamed CIA official wrote. “There is no agreement. DoD elements (USAF, NRO, JCS, ISA) all believe it should be withheld from public release. NASA, and to a large degree State, has taken the position that it should be released—that is, allowed to go into the Sioux National Repository and to let nature take its course.”

What the memo indicates is that there was a difference between the way the civilian agencies of the US government and the military agencies looked at their roles. NASA had ties to the military, but it was clearly a civilian agency. And although the reasons why NASA officials felt that the photo should be released are unknown, the most likely explanation is that NASA officials did not feel that the civilian agency should conceal any of its activities. Many of NASA’s relations with other organizations and foreign governments were based on the assumption that NASA did not engage in spying and did not conceal its activities.

The CIA memo writer added, “There are some complicated precedents which, in fairness, should be reviewed before a final decision.” These included “A question of whether anything photographed in the United States can be classified if the platform is unclassified; Such complex issues in the UN concerning United States policies toward imagery from space” and “the question of whether the photograph can be withheld without leaking.”

The space shuttle crew of STS-78, orbiting the Earth in 1996, also photographed Groom Lake. (credit: NASA) |

Secret as an onion

A cover note to the memorandum, written by the Director of Central Intelligence William Colby himself, stated that “I confessed some question over need to protect since: 1-USSR has it from own sats. 2-What really does it reveal? 3-If exposed don’t we just say classified USAF work is done there?”

Colby’s questions were unusual given the debates that have raged within the US intelligence community for decades over the need for secrecy. Those within the intelligence community who have asked “what is the harm in acknowledging the obvious?” have almost always lost the argument, and the obvious remained classified.

| Groom Lake has been a more ambiguous case. The US government has at times acknowledged and at other times refused to acknowledge its existence. |

Government officials have frequently argued over the need to refuse to confirm even the most basic knowledge about things that have been widely reported in the press for decades. For instance, the existence of the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), which manages America’s spy satellite program, first became known in a 1971 New York Times article (a decade after the NRO was created), but arguments flared up within intelligence circles for the next 20 years over whether or not to confirm its existence. Finally, in September 1992 the “fact of” the existence of the NRO was revealed in a terse press release that never even used the word “satellite.” Even after that decision, for several years the NRO refused to confirm that it actually launched satellites on rockets, another glaringly obvious fact.

Groom Lake has been a more ambiguous case. The US government has at times acknowledged and at other times refused to acknowledge its existence. Author Peter Merlin wrote a detailed chronology of all the times the US government publicly acknowledged the existence of a facility at Groom Lake. (See: “It’s No Secret – Area 51 was Never Classified.”) The existence of an airstrip at Groom was revealed when it was first constructed. But at other times the government refused to acknowledge the facility’s existence, only to later confirm it. In 1998, the US Air Force issued a terse statement acknowledging that the facility did indeed exist, even though photos taken on the ground and overhead had been available for decades. In fact, at least two US Geological Survey aerial photographs of Groom taken in 1959 and 1968 had been available in public archives, but not discovered until many years later. In 2013 there were widespread reports that for “the first time,” the US government was acknowledging activities there, despite all the other times it had already done so. The distinction was that for the first time the government had acknowledged a specific activity at the facility—the testing of the U-2 spyplane—as opposed to simply admitting a facility existed.

There is some logic to the secrecy policy of refusing to confirm the “fact of” an organization, or even an airbase in the Nevada desert. Intelligence officials often refer to secrecy being like an onion, and each layer that is peeled off reveals a little more of what is contained within. Even if the next layer is visible in vague form, the advocates of strong secrecy want to keep all the layers in place.

This policy is usually given solid form in legal discussions within government agencies. There the concern is not so much with foreign intelligence agencies, but with American citizens and the press, and their ability to request the declassification of government documents through the Freedom of Information Act. By refusing to even acknowledge the existence of something, government agencies have erected an outer legal barrier against requests for information from their own citizens. Author M. Todd Bennett addresses this subject in the context of the Glomar Explorer case in his new book Neither Confirm Nor Deny – How the Glomar Mission Concealed the CIA From Transparency. The Glomar incident also occurred in 1974, and the CIA—still under the leadership of Colby—erected a substantial policy barrier to protect its secret operations only a short time after Colby seemed to take a more relaxed position in regards to the Skylab photograph. (For more, see: Jeffrey T. Richelson, “Intelligence Secrets and Unauthorized Disclosures: Confronting Some Fundamental Issues,” International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, 2012; and Jeffrey T. Richelson, “Back to Black,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 2001.)

A new book by M. Todd Bennett delves into how the CIA erected higher barriers to secrecy starting in 1974, the same year that the agency debated over the release of the NASA photograph of Groom Lake. |

But critics of excessive government secrecy argue that such policies are often pursued unnecessarily, since no law requires the government to reveal anything further about a facility such as Groom after acknowledging its existence. The onion analogy holds validity, but can also be taken too far; after all, the Soviet Union was an extremely secret society and classified things such as road maps, something that had never been classified in the United States.

| Although there are no declassified documents indicating how this dilemma was resolved, it seems like NASA, the State Department—and apparently Director of Central Intelligence Colby—got their way. |

Secrecy critics also argue that there is something wrong when America’s adversaries have better information about the federal government’s actions than its own citizens. Groom Lake had obviously been photographed numerous times by Soviet spy satellites at high resolution before the Skylab astronauts took their low-resolution photo. Refusing to release a single fuzzy photograph from a Skylab mission was taking an abstract ideal—maintaining all the layers of the onion—to an absurd extreme. These critics also argue that when the government fails to confirm the obvious, it both undermines governmental authority and legitimacy, and contributes to wild speculation, such as aliens and soundstages in underground hangars at Area 51. And despite the best efforts, information will still seep out. After all, while various agencies of the federal government were arguing over whether or not to put this low-resolution photograph in an unclassified government archive, nobody realized that several other higher-resolution images were already sitting in that archive, awaiting discovery.

Although there are no declassified documents indicating how this dilemma was resolved, it seems like NASA, the State Department—and apparently Director of Central Intelligence Colby—got their way. The photo was released to a government archive and went unnoticed for several more decades. Ironically, the earlier USGS photos were publicly revealed first. Two decades later, during STS-78, a space shuttle crew would also photograph Groom. But whether or not that caused concern within the intelligence community is unknown. Or at least still classified.

Groom Lake was photographed by Europe's Sentinel spacecraft in 2022. (credit: Wikimedia Commons) |

Dwayne Day is can be reached at zirconic1@cox.net.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.