SpaceX and the Blank Slate

Starting anew vs. tried and true

Posted by Casey Dreier

2016/09/28 15:20 UTC

Topics: commercial spaceflight, SLS, Humans to Mars, Future Mission Concepts, human spaceflight, Mars

Elon Musk’s announcement of his plans to colonize Mars inevitably invites comparisons to NASA’s efforts to land humans there in the mid-2030s. Both plans are being picked apart and analyzed for feasibility, cost, and their abilities to form political and industry coalition support. But this ignores a fundamental difference between the two organizations: SpaceX is designing a perfect system from a blank slate, while NASA is piecing together an imperfect solution from things already in existence.

Imagine you have a problem you want to solve.

Now imagine sitting down at your desk, laying out a blank piece of paper, grabbing your favorite pencil, and getting to work. Your strategy is simple: start with your goal and work the problem backwards. When you find the solution, you stop.

Alternatively, imagine sitting down at your desk, but instead of your blank sheet of paper, you open a notebook full of other people’s work. Instead of your favorite pencil, you use that big pen they give away for free at the bank. Instead of starting with the goal and working backwards, you start with a large set of smaller problems that have already been solved, assume some initial conditions, and then attempt to solve your problem by piecing them all together.

SpaceX’s Interplanetary Transport System, which has the goal of sending one million (!) humans to settle Mars over the next 60 years, is the ultimate blank slate approach to the problem of sending humans to Mars.

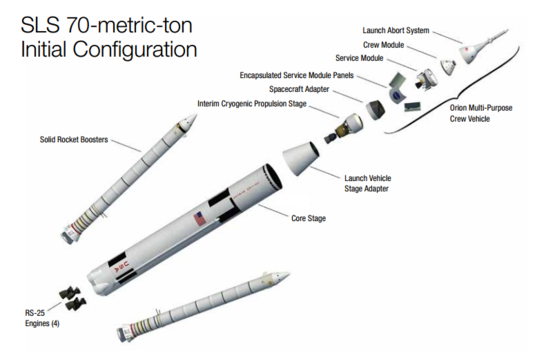

NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and Orion crew capsule, which will begin launching humans in the early 2020s to the vicinity of the Moon, is an example of the piecewise solution for a journey to Mars.

SpaceX’s plan calls for everything to be new: a new engine (the Raptor), a new rocket (the ITC), a new spacecraft, new material composites and processes, in-orbit refueling, precision landing and same-day turnaround of a massive first-stage of its rocket, etc.

NASA’s Space Launch System rocket uses a different approach. It uses upgraded Space Shuttle Main Engines, the RS-25s; upgraded Shuttle-era solid rocket boosters, the upper stage will use existing engines (the RL-10s), the infrastructure is upgraded Shuttle infrastructure, and so on. These decisions weren’t made out of the blue, they were, in fact, mandated by Congress in the 2010 NASA Authorization Act. NASA was given the pieces and told to solve the problem of human spaceflight.

This is the conservative approach taken by aerospace companies when funding is limited: avoid making new stuff. Just look at nearly every recent Mars exploration architecture concept (such as the orbit-first concept we highlighted from a study team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory or Lockheed-Martin’s Mars Base Camp). These Mars exploration architectures use existing NASA field centers and contractor workforces, piece together the parts of existing NASA programs, use as much flight-proven hardware as possible. Again, when funding is tight, particularly year-to-year funding, the best practice is avoid the risk of creating new hardware.

That’s because creating new, reliable space hardware is historically the source of cost and schedule overruns. NASA has been dogged by this problem over the decades, overselling and under delivering on its initial goals. But it’s not unique to NASA. Every institution (and every human) struggles with this all of the time—it’s called optimism bias. We assume the best possible outcome and downplay the negative ones. But it is impossible to anticipate all of the unknown unknowns that arise from the multitudinous interactions of complex systems. NASA has been burned by this many times, driving the conservative approach to hardware program and risk to prevent undue attention from a prickly Congress.

SpaceX doesn’t work for Congress. It’s a privately-held company, so they don’t have to answer to shareholders. SpaceX has the luxury to choose its own workforce, choose its own production sites, and use its own funding to develop any hardware it wants. The company has a clear vision that informs every aspect of their work.

It’s fun to design on the blank slate. Everything works perfectly, everything happens on time and on budget. But designing on a blank slate is risky since the real world has a nasty way of throwing problems your way. There will be engineering, political, and economic complexities that will disrupt this plan.

So perhaps the most important—and most revealing—moment came in the middle of Elon Musk’s presentation to the International Aeronautical Congress, when he said that the reason he is personally accumulating assets is to fund his Mars colonization plan. This is his life’s work. So when we talk about schedules, feasibility, and cost, balance that out with the fact that this is Musk’s life work. Elon Musk wanted to colonize Mars to save humanity, so he grabbed a blank piece of paper, worked backward, and founded SpaceX.

Other related posts:

Or read more blog entries about: commercial spaceflight, SLS, Humans to Mars, Future Mission Concepts, human spaceflight, Mars

You frame these as risks that are unique (or at least more probable) with newly designed hardware, and which can be mitigated by emphasizing the use of existing hardware. But that is not necessarily the case.

Only legitimate scientific organizations such as NASA, and only after rigorous planetary protection plans, should be allowed to send human investigators, not colonists.

SpaceX has a clear record of huge cost reductions. E.g. NASA’s Dan Rasky, discusses a study of F1/F9 dev cost vs the NASA/USAF cost model - https://youtu.be/xYpvvq0fqwE. The model said $4B but SpX spent only $400M. F9 launch costs are 2-3 lower than competitors, who must now develop new LVs. (Yes, there have been F9 failures but same for other LVs in early operations.)

The Society, Explore Mars, etc. will strain their credibility to the breaking point if they continue to put out “affordable” Mars plans that ignore SpX (and Blue Origin, etc) and the huge gains in costs and capabilities they can provide.

That would essentially equate to one MAVEN anyway, both in terms of cost and instrumentation, so what would be the point?

And even that would be assuming you would be sending those nine MOMs all at once. If instead NASA sent them one at a time then it would be taking about 20 years (assuming 26 months between missions) to obtain the same data that a single MAVEN acquired in a single mission.

Imagine if NASA took that same, low-budget, serial approach with ALL its Mars missions, landers as well as orbiters. At that rate to get to where we are today in terms of knowledge about Mars, it would take NASA until sometime NEXT century to obtain the same information about Mars that it has acquired to date.

In short, you get what you pay for.

It's much less fun to watch NASA hack away at problems of politics, policy, and funding.

But the truth is, supporters of space exploration must solve both types of problems in order to build a robust, fruitful, sustained program.

Presidents and Congresses come and go. Companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin can't pay for crewed missions on their own, at least not indefinitely, because there is no viable business model for exploration. Tourism, maybe. But one tragedy can bring that approach to a halt pretty quickly.

I am a member of the Planetary Society because its members are tackling both problems: technology and policy. The organization may be out-sized by these challenges, but tackling only one at a time seems like a mission to nowhere.

Once transport to Mars is cheap (he thinks $200k per person trip is realistic), there will be enough adventurous individuals who can raise the funds to pay for their trip. People would sell their homes. Wealthy parents could - highly reluctantly - pay for their children. Foundations and crowdfunding drives would pay for highly talented younger people to make the trip.

As soon as this dynamic starts gathering momentum, and it seems like the Mars colony is really happening, everyone else will jump on the bandwagon. Corporations will want to be there. Nation states will want to establish their own presence. The floodgates of private and government money open.

You just have to jump start this process, and it becomes self-sustaining. Musk is willing to do what it takes, including investing his private fortune which he only made for this one purpose.

I'm no expert in genetics, but it seems reasonable to me that DNA analysis is or will be sophisticated enough to distinguish between microbes that have been on