Moon ice may be much easier to harvest than previously thought — and it could be the 'first step' in building a space economy

- Ice may be exposed at hundreds of locations on the surface of the moon, a new study suggests.

- This surface water appears to be trapped in shadowed craters at the lunar poles.

- Robotic or human missions could harvest lunar ice and turn it into fuel for spacecraft.

- However, engineers who study space mining say we need to send rovers into craters to find out how wide and deep the ice deposits go.

Shadowy craters near the moon's poles may hide untold reserves of ice — an incredibly precious resource in space — within reach of robotic and human explorers.

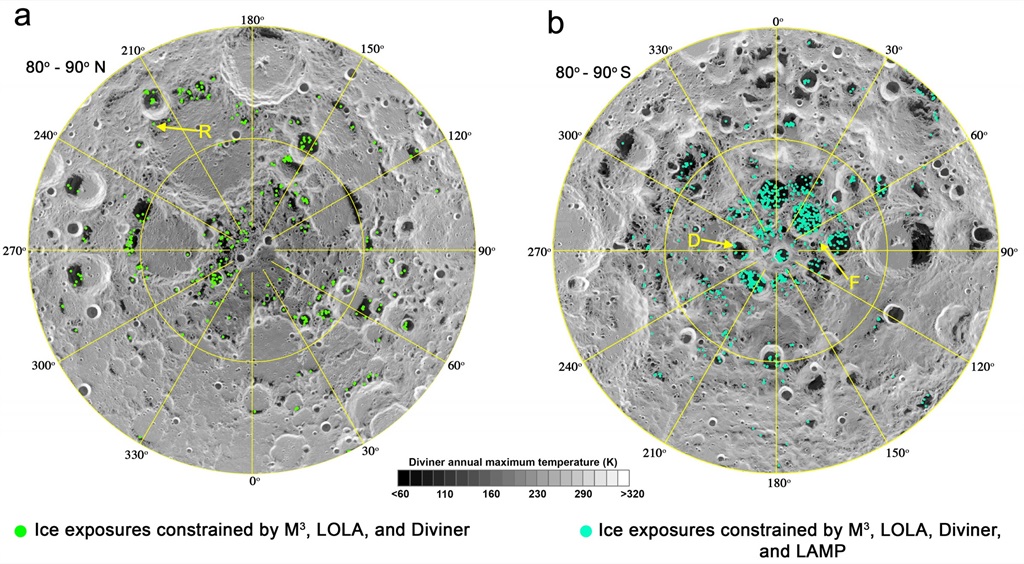

That's one big takeaway from a new study published on Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The researchers took data from US and Indian lunar spacecraft, then compared it to computer simulations of how surface ice might look to those robots.

Their model detected hundreds of locations on the moon where ice may lurk very close to or directly at the moon's surface.

Leslie Gertsch, a geological and mining engineer at the Missouri University of Science and Technology, called the new data sophisticated and specific — though not a surprise.

"This idea has been around for awhile," Gertsch, who studies how to extract resources in space, told Business Insider. "But this study says, 'yeah, there really does seem to be water ice at the surface of the moon'."

If true, these spots might be compelling places to mine the moon's ice deposits.

"There's a need to know if there's ice on the surface in order to extract it," Angel Abbud-Madrid, director of the Centre for Space Resources at the Colorado School of Mines, told Business Insider. "This is one more step closer to prospecting the moon and showing how accessible its ice is."

Finding easy-to-extract deposits of lunar ice would do more than give astronauts something to drink. Water can be split into its atoms — hydrogen and oxygen — which could make a fuel for rocket engines that could power a new era of space exploration.

"Extracting ice from the moon would be a first step in building a space economy," Abbud-Madrid said.

With ample fuel derived from moon water, perhaps Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos might realise his vision to move all industry off Earth, and Elon Musk his own of settling Mars with a permanent human colony.

But Abbud-Madrid and Gertsch, neither of whom was involved in the study, say we aren't yet ready to start mining the moon, let alone dominating the solar system.

Mapping the moon's icy cold traps

The moon — an airless, 4.5-billion-year-old rock — is a terrible place to be if you're surface water and want to stick around for awhile.

Lunar daytime temperatures can soar beyond the boiling point of water, and ice exposed to a vacuum will sublimate (or turn directly into a gas) with the least bit of jostling or warmth. The process is similar to how dry ice, or frozen carbon dioxide, slowly vanishes when exposed on Earth. A "wind" of particles from the sun also blows any free gases on the lunar surface out into space.

However, researchers have speculated for decades about the existence of "cold traps" in permanently shadowed craters on the moon. Such regions are so cold that they keep any water there frozen, and might even freeze water vapour that passes by — much the same way a freezer pack attracts a coating of frost on a humid day.

The idea of these cold traps has got a boost in recent decades, thanks to moon-orbiting spacecraft like NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and India's Chandrayaan-1. A probe called the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) even smashed into one of these craters and tossed up the dirt to see what was there.

"They found water, they found mercury — all kinds of cool things, and more than usual," Gertsch said.

While that probe didn't find out how close to the surface water might be, the new study hints that about 3.5% of lunar cold traps may have ice exposed at the surface, perhaps as a frost. But there's still no estimation of the depth of the prospective ice deposits.

"When people think of the tip of an iceberg, they think it's much bigger underneath. That might not be the case here," Gertsch said. "It could be the tip of an iceberg. But if we're talking about frost, it could be a very, very small iceberg."

To figure out what's there — and what isn't — both Abbud-Madrid and Gertsch say we need "ground truth."

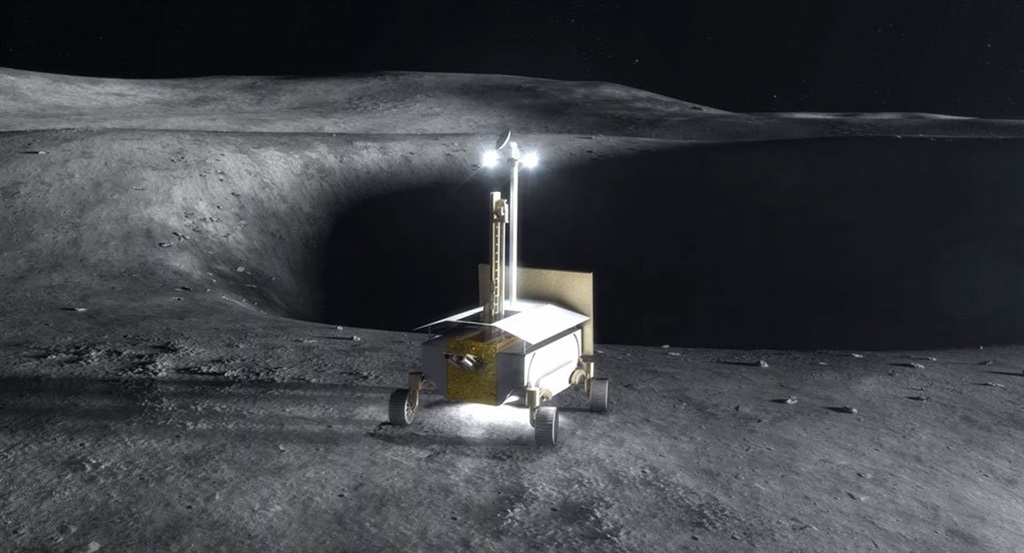

"We need to send a little rover down, better yet a few, and poke into some of these partially and permanently shadowed regions," Gertsch said. "We actually need to go there and drill down to see how far down and how wide the deposits go."

A rover could also assess the quality of the ice. If it's pure, it could be relatively easy to extract. But if it's mixed in with lunar soil, called regolith, mining could prove more challenging.

How to mine the moon

Assuming there is enough lunar surface ice to mine, harvesting it won't be straightforward. Just bumping into some lunar ice and exposing it to the vacuum of space can make it vanish as a gas.

"Digging and carrying ice to some processor may not be the best. You'd lose a lot of it," Gertsch said. "Nobody is really thinking about that, and they should."

During a June meeting at the Colorado School of Mines, several researchers met to brainstorm methods of mining the moon. Abbud-Madrid discussed using three solar reflectors (basically giant mirrors) to extract lunar surface ice with hardly any digging at all.

"You redirect that energy to the surface, inside tents," he said. "It will hit the ice and sublimate it inside the tent."

From there, the surface of the tents would act as cold traps, collect the water vapour, and then move it to a processing plant. The processing plant would use electricity to split the water into hydrogen and oxygen, separate the gases, and store them as liquids.

"By doing that you will have the hydrogen and oxygen prepared for a rocket that can land there," Abbud-Madrid said.

But he added that extra fuel could even be stored in tanks and lifted into orbit around the moon.

"You start making gas stations in space. This really starts cutting your dependence on bringing all that fuel from Earth," he said. "That's really been what's holding us back from deep-space exploration."

But no mineral deposit is 100% guaranteed. Even on Earth, humanity's record for starting a productive and long-lasting mining operation is poor; for every successful prospect, Gertsch says there are between 500 and 10,000 failures.

"We have different techniques today and can make use of better information," she said, adding that today's advanced electronics are better than prospecting on horseback with a pick axe. "But it's still not easy."

The 239,000-mile (about 384,000km) distance to the moon, the vacuum of space, and high radiation levels only raise the stakes.

Many researchers see asteroids or comets as another option for mining, but they're much further away and move around. So Abbud-Madrid said mining the moon makes a lot more sense — if it has accessible water deposits.

"The moon is close. It's right there," he said. "You could even mine it via remote-control."

No comments:

Post a Comment