The scarcity of lunar resources like volatiles illustrates the need to deconflict activities on the Moon in a way that is acceptable by all participants. (credit: NASA) |

Is outer space a de jure common-pool resource?

by Dennis O’Brien

Monday, October 25, 2021

As 2021 comes to a close, humanity is facing a historical crisis, when just a slight change will lead to widely different futures. The closest parallel occurred five centuries ago, when countries with advanced technology sought to exploit the resources of “new” worlds. The resulting Age of Imperialism was marked by needless war, suffering, and neglect, whose effects are still being felt today. How close are we to repeating that pattern? What role can space law play in avoiding it?

| Article II of the OST creates a de jure common-pool resource of outer space and that all subsequent norms, agreements, and activities are subject to it. Any act of exclusion, even for “safety zones,” violates Article II. |

As accessing and developing outer space resources becomes more feasible, determining the status of those resources under international law and norms becomes more important. The oldest and most widely accepted binding international treaty is the Treaty On Principles Governing The Activities Of States In The Exploration And Use Of Outer Space, Including The Moon And Other Celestial Bodies, aka the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 (OST). The most recent proposed norms are the Artemis Accords (Accords), an inter-agency agreement adopted by NASA and its partners as part of the Artemis Moon program. This article concludes that Article II of the OST creates a de jure common-pool resource of outer space and that all subsequent norms, agreements, and activities are subject to it. It further concludes that any act of exclusion, even for “safety zones,” violates Article II and defeats the common-pool resource. It proposes that sharing access to resources will mitigate the exclusion, maintain the common-pool resource of outer space, and allow resource development activities, including the removal of materials in place (in situ). Finally, it will consider whether the Moon Treaty, with an implementation agreement based on sharing and cooperation, can enhance the development of outer space resources, including the building of permanent settlements.

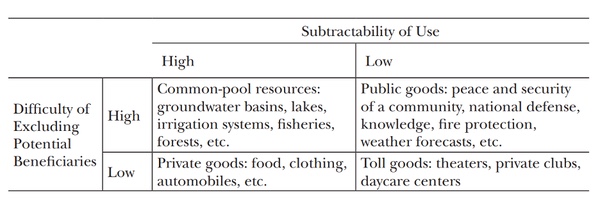

The four categories of goods and resources

Economist Elinor Ostrom received the Nobel Prize in 2009 for her work describing categories of goods/resources. She divided them into four categories depending upon two factors: are they excludable and are they subtractable (aka rivalrous)? She created a grid to demonstrate her analysis:[1]

Figure 1 |

A Private Resource is one that is both 1) excludable, i.e. an entity/group can exercise private property rights, preventing others from accessing/using the resource; and 2. Subtractable (or rivalrous), i.e. use/consumption by one entity/group necessarily reduces the amount available for use/consumption by others. Examples include food, clothing, and automobiles. A more relevant example is an exclusive claim to the mining, recovery, or utilization of a resource.

At the other end of the spectrum are Public Resources, sometimes called a Commons. They are both non-excludable (anyone can access/use them) and non-subtractable (use by anyone does not subtract from the availability of the resource for use by others.) Examples include free-to-air television, open-source software, and, in outer space, solar energy.

In between Private and Public Resources are Toll (or Club) Resources and Common-Pool Resources. A Toll/Club Resource is like a Private Resource in that it is excludable to those who are not members of the club, but it is not subtractable to those entities who are members of the club, i.e., use will not deplete the resource or make it less accessible to other club members. A prime example is paid satellite communication services (video, sound, data, GPS.) No matter how many entities use them, they are still available to those who pay the toll.

A Common-Pool Resource, by contrast, is not excludable; it can be accessed/used by any person, entity, nation, or group of nations. But it is also subtractable: use by anyone means less to use by anyone else unless there is some way to replenish the resource. On Earth these include resources that are beyond the exclusive claim of any national jurisdiction, such as ocean fishing stocks and undersea mineral deposits. In outer space, they include water ice in eternally dark craters, peaks of eternal sunlight that can harvest solar energy (the peaks themselves, not the sunlight), favorable locations for habitats (e.g., proximity to the poles or lava tubes), and mineral-rich asteroids.

| Article II’s prohibition against appropriation means that no State Party can claim exclusive ownership or right of use of any location or resource in outer space. Exclusion equals appropriation. |

Ostrom noted that “This basic division [between private and public goods] was consistent with the dichotomy of the institutional world into private property exchanges in a market setting and government-owned property organized by a public hierarchy.” Her contribution: “Adding a very important fourth type of good – common-pool resources – that shares the attribute of subtractability with private goods and difficulty of exclusion with public goods.”[1] Thus the title of her lecture: Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems.

The non-excludability of space resources

But why are outer space resources non-excludable? Throughout history, sovereign states have claimed such resources for their exclusive use, usually on a first-come, first-served basis. This process was accelerated during the Ages of Exploration, Colonialism, and Imperialism of the past five centuries. It continues today in the Arctic as more resources become accessible. Within nations, under national laws, individuals and corporations have established exclusive claims to resources through discovery, access, and use. Why can’t sovereign states and their nationals do the same concerning outer space resources?

The answer is the Outer Space Treaty. It entered into force on October 10, 1967. As of 2021, it has 111 States Parties, including all spacefaring countries. It has been called the “Constitution of Space Law” and is the basis of all discussions for the governance of humanity’s future in outer space.

The section of the OST that is most relevant to the current discussion is Article II, which states in its entirety:

Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.[2]

Article II’s prohibition against appropriation means that no State Party can claim exclusive ownership or right of use of any location or resource in outer space. Exclusion equals appropriation. By prohibiting exclusion, the ban on appropriation creates a de jure (by law) common-pool resource of outer space.

This prohibition against exclusion also applies to any national of a State Party, i.e., any individual, corporation, or any other private or public entity:

Article VI: States Parties to the Treaty shall bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, whether such activities are carried on by governmental agencies or by non-governmental entities, and for assuring that national activities are carried out in conformity with the provisions set forth in the present Treaty.[2]

The problem with the Artemis Accords

The Artemis Accords seek to facilitate the use of outer space by allowing entities to remove materials from “in place”, thereby acquiring private property rights in the materials:

SECTION 10 – SPACE RESOURCES

2. The Signatories emphasize that the extraction and utilization of space resources, including any recovery from the surface or subsurface of the Moon, Mars, comets, or asteroids, should be executed in a manner that complies with the Outer Space Treaty and in support of safe and sustainable space activities. The Signatories affirm that the extraction of space resources does not inherently constitute national appropriation under Article II of the Outer Space Treaty, and that contracts and other legal instruments relating to space resources should be consistent with that Treaty.[3]

Countries including the United States, Japan, and Luxembourg have passed national laws that grant private property rights to their nationals who extract and utilize space resources.[4] The Agreement Governing The Activities Of States On The Moon And Other Celestial Bodies, aka Moon Treaty, also distinguishes the ban against owning resources in place from ownership once they are removed:

3. Neither the surface nor the subsurface of the moon, nor any part thereof or natural resources in place, shall become property of any State, international intergovernmental or non- governmental organization, national organization or non-governmental entity or of any natural person.[5] [emphasis added]

But the Artemis Accords go further than granting property rights to resources that are no longer in place. They establish exclusive zones for space resource activity, an action that is not widely accepted.[6] Though they are given the innocuous title of “safety zones,” they nevertheless rely upon exclusion. They do so in Section 11, “Deconfliction of Space Activities,”[3] in the following manner:

- They establish a unilaterally declared size for the zone that depends on the nature of the activity, but without any other limitations (Paragraph 7(a)). An entire eternally dark crater could be designated a zone of activity for removing all the water ice there.

- They are unlimited in duration, ending only when the resource activity is completed (7(c)). This would exclude any other party from accessing the resource until it was totally depleted.

- Any effort by another party to access resources in the unilaterally declared zone is deemed to be “harmful interference” and a violation of Article IX of the OST.

| Sharing access to resources mitigates the exclusive nature of the zones; there would be no violation of the Article II prohibition against appropriation. |

Exclusion by any other name, including safety, is still exclusion, and exclusion is appropriation, which is specifically prohibited by Article II of the OST. Therefore, Section 11 of the Artemis Accords, as currently written, violates the Outer Space Treaty. The pronouncements in Section 11, and throughout the Accords, that they are intended to comply with the Outer Space Treaty are not enough to negate the exclusionary nature of the “safety” zones.

Fortunately, the solution is simple. The parties to the Artemis Accords need only add the following sentence to the Accords, perhaps as a new sub-paragraph between Section 11 paragraph 7(c) and 7(d): “Access to resources shall be shared; any activity within the zones shall be conducted in such a manner that other parties can safely access any resource located there.” This is a restatement of Moon Treaty Article 9:

A State Party establishing a station shall use only that area which is required for the needs of the station… Stations shall be installed in such a manner that they do not impede the free access to all areas of the moon of personnel, vehicles and equipment of other States Parties conducting activities on the moon. [5a]

Sharing access to resources mitigates the exclusive nature of the zones; there would be no violation of the Article II prohibition against appropriation. Indeed, if the above provision is adopted, then much of the language in the Accords that mitigates the effect of exclusionary zones becomes superfluous.

We have already reached the point when sharing information about future activities can help avoid conflict. Every public and private entity that is interested in utilizing or developing an outer space resource should declare its intentions as soon as possible to promote cooperation and facilitate sharing access to resources.

The subtractable/rivalrous nature of outer space resources

Sharing access to resources addresses one of the issues presented by the de jure common-pool resource of outer space that is created by Article II of the Outer Space Treaty. But there is another issue that must be addressed, the other side of the coin of any common-pool resource: the finite, limited nature of space resources.

Although the OST prohibits exclusion, it does not prohibit the acquisition and/or use of outer space resources. If outer space resources were infinite, this would not be a problem. Outer space would be considered a non-exclusive, non-subtractable public resource, a true public commons. But there are practical limits to the amount of space resources that can be accessed, primarily due to limits in current Earth technology for reaching and utilizing them. Although outer space is de jure non-excludable, it is nevertheless de facto subtractable, and thus a common-pool resource with the potential for conflict.

Examples of subtractable resources on the Moon include water ice in the craters of eternal darkness at the poles, along with the peaks of eternal sunlight where solar energy can be harvested. Note that the sunlight itself is not a subtractable resource; it is the land and its location that is. Land has been considered a resource ever since the development of classical economic theory: it is tangible, its boundaries can be determined, and its value can be defined by its usefulness (i.e., the more useful the land at a given location, the more valuable it is as a resource).

There are different models for managing subtractable resources. The Artemis Accords rely on an exclusionary first-come, first -erved private property model. But as explained above, that model is prohibited by the Outer Space Treaty. It thus becomes necessary to create a new model, a new set of norms/agreements, that will provide the minimum legal structure necessary to support outer space activity.

The Space Treaty Institute has been working on such a legal framework since 2017. After much drafting, consultation, and revision, it has produced a Model Implementation Agreement for resource utilization/management under Article 11 of the Moon Treaty that satisfies the requirements of Article II of the OST. It is based on three organizational guidelines:

- The Agreement must support all public and private activity;

- It must protect essential public policies;

- It must integrate and build upon current institutions and processes.

The Model Implementation Agreement includes seven basic principles and processes:

- Share access to resources, including materials and land/locations;

- Share information, including the discovery of resources;

- Register activities;

- Develop standards, recommended practices, and interoperability;

- Protect the natural environment and scientific/historical sites;

- Establish dispute resolution, including consultation, arbitration, and mediation;

- Honor rights of individuals and settlements.

The proposed Model Agreement is not meant to address all conceivable issues, only those that are required at this time to protect essential public policies while providing the legal support necessary for sustainable public and private activity. The Moon Treaty itself calls for the review and possible revision of any implementation agreement every ten years as part of adaptive governance.

The full ten-paragraph Model Implementation Agreement can be found at www.spacetreaty.org.

The need for an international framework of laws to manage space resource activity

Why is this proposal necessary? As of late 2021, there is no internationally recognized mechanism for managing the utilization of space resources, including the land used for public or private activity. The current controlling international law is the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which prohibits any one country or its nationals from appropriation in Article II.

| The hopes and dreams of individuals and groups to create new societies in outer space are just as important as the entrepreneurship of those seeking to engage in space commerce. Both must be recognized, honored, and nurtured if humanity is to leave our home planet in a sustainable manner. |

Many countries agree that the prohibition against appropriation prevents any one country from granting exclusive property rights. But, as noted above, some disagree, enough to create the potential for conflict and uncertainty for businesses and investors. Since the function of law includes avoiding conflicts and reducing uncertainties, it is imperative to create an international legal framework now for resource utilization activity in outer space.

The Moon Treaty provides the international authority to manage resource utilization. Article 11 does not prohibit resource utilization; it just prohibits any one country or group of countries from imposing their exclusive regime on others:

11.1. The moon and its natural resources are the common heritage of mankind, which finds its expression in the provisions of this Agreement, in particular in paragraph 5 of this article.

11.2. The moon is not subject to national appropriation by any claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

11.3. Neither the surface nor the subsurface of the moon, nor any part thereof or natural resources in place, shall become property of any State, international intergovernmental or non-governmental organization, national organization or non-governmental entity or of any natural person. The placement of personnel, space vehicles, equipment, facilities, stations and installations on or below the surface of the moon, including structures connected with its surface or subsurface, shall not create a right of ownership over the surface or the subsurface of the moon or any areas thereof. The foregoing provisions are without prejudice to the international regime referred to in paragraph 5 of this article…

11.5. States Parties to this Agreement hereby undertake to establish an international regime, including appropriate procedures, to govern the exploitation of the natural resources of the moon as such exploitation is about to become feasible. [emphasis added] [5]

Note that Article 11 begins by stating that the “common heritage of mankind” is defined by the Moon Treaty and its implementation agreement. The CHM has no legal meaning or force of law beyond the framework that the States Parties adopt. Concerns that the CHM will result in a loss of sovereignty are misplaced and should not deter interested parties from considering the benefits of the Moon Treaty. The purpose and intent of Article 11 is to authorize the States Parties to create an international legal framework for managing resource utilization, so long as they do it together.

Limited central authority

Some fear that the Moon Treaty will create an overriding central entity. But polycentric governance of complex systems means that there is no need to establish a new governing body or agency. Limited authority, with specific principles and processes, is vested in treaties, and the States Parties mutually enforce the requirements using dispute resolution mechanisms.

A prime example of how this works today is the Svalbard Treaty (1925), regarding an archipelago near the Arctic Circle. Although it is nominally under the jurisdiction of Norway, any country that signs the Treaty can access any of the resources there, so long as they abide by certain principles such as non-military activity and protecting the environment. Current States Parties include Russia, China, the United States, and 43 others. The Treaty is administered by Norway, which provides the limited central authority.[7] But in outer space such authority can be provided by a treaty, such as the Moon Treaty with the Model Implementation Agreement, and mutually enforced by the member states.

Most of the Model Implementation Agreement deals with the utilization of resources and has been explained above. But a few more topics merit further explanation.

Developing standards and practices

The Model Implementation Agreement requires the States Parties to develop standards and recommended practices (SARP’s)—sometimes called “best practices”—for the development of outer space resources (Paragraph 6.) It does not create a super-agency that will override efforts that have been developing organically, though it does mandate that “standards or practices shall not require technology that is subject to export controls.” Rather, it requires the States Parties work with NGE’s, providing them a seat at the table and the legal support needed for their work. The International Organization for Standards (ISO)[8], the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR)[9], the Hague Group[6], the Moon Village Association[10], For All Moonkind[11], and the Space Treaty Institute[12] are examples of such organizations.

The Treaty anticipates that there will be ongoing advances in technology that will require a constant updating of standards and practices. It is essential for the States Parties to integrate the work of NGE’s into this process. Otherwise, a vast pool of talent and innumerable hours of work will be wasted. Without them, any governance of the common-pool resource will lack widespread organizational support and will likely fail.

Protecting historical and scientific sites

Article 7.3 of the Moon Treaty authorizes the preservation of sites of scientific interest:

States Parties shall report to other States Parties and to the Secretary-General concerning areas of the moon having special scientific interest in order that, without prejudice to the rights of other States Parties, consideration may be given to the designation of such areas as international scientific preserves for which special protective arrangements are to be agreed upon in consultation with the competent bodies of the United Nations. [5]

The Model Implementation Agreement clarifies that “special scientific interest” includes historical and cultural sites (Paragraph 7.) It is unclear whether a new organization/process will need to be established to meet these goals or if the task will be given to an existing organization (“competent body”) such as UNESCO. Until such decisions are made and procedures in place, the Model Implementation Agreement protects sites that are more than 20 years old.

Resolution of disputes

One of the best ways to provide minimal overall management of space resource activities is to let the interested parties sort out their differences themselves. Doing so requires establishing a process for resolving disputes.

Article 15 of the Moon Treaty describes levels of dispute resolution, beginning with consultations between the States Parties. Any other State Party can join in the consultations, and any State Party can request the assistance of the Secretary-General of the United Nations. If consultations fail to resolve the dispute, the States Parties are instructed to “take all measures to settle the dispute by other peaceful means of their choice appropriate to the circumstances and the nature of the dispute.” (Art. 15.3)

The Model Implementation Agreement also allows parties to voluntarily choose binding arbitration under the Permanent Court of Arbitration.[13] It also authorizes enforcement of any decision/award under a widely accepted convention. (Paragraph 9)

Non-binding mediation is also available, now that there is a separate international convention for enforcing any resulting agreements.[14] The decisions and agreements reached during any dispute resolution will help form the customary international law that will guide future activity.

Individual rights

What if an inhabitant of a settlement seeks asylum in another country’s facility? The Moon Treaty and the Outer Space Treaty contain certain provisions that suggest that their country of origin retains jurisdiction and can have them returned.

| The mission of space law must be nothing less than to restore that hope, to inspire humanity by giving the people of our planet a future they can believe in. |

Such control would conflict with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”), which states in Article 14.1 that “Everyone has the right to seek and enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.” [15] The Model Implementation Agreement incorporates the protections of the UDHR (Paragraph 10.) As explained above, this would override national laws and allow individuals to remove themselves from the legal authority of one country and enter the authority of another.

Settlements

Including the land used for settlements in the definition of “resources” is essential for creating an international framework of laws that is sufficiently comprehensive to support all private activity in space. It is the only way to override the prohibitions against appropriation in both the Outer Space Treaty and the Moon Treaty (see above.) This is done by interpreting “the exploitation of the natural resources of the moon” in Article 11.5 to include the use of any land/location on the Moon for any purpose.

When the Moon Treaty was first proposed, some individuals and NGEs, led by the L5 Society (now merged with the National Space Society), opposed it because there were no provisions for establishing private settlements with their own governance.[16] They pointed again to Articles 11.2, which states that “the moon is not subject to national appropriation by any claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means,” and 11.3’s prohibition against ownership. But as explained above, the international framework of laws authorized by Article 11.5 overrides those prohibitions. The proposed Model Implementation Agreement confirms that a settlement can seek autonomy and/or independence through customary international law (Paragraph 10.) In doing so, it promotes the principles of polycentrism and subsidiarity (governance as local as possible) while discouraging tendencies such as colonialism and over-control by a centralized authority. Some governance is essential, but the government that governs least governs best.

The hopes and dreams of individuals and groups to create new societies in outer space are just as important as the entrepreneurship of those seeking to engage in space commerce. Both must be recognized, honored, and nurtured if humanity is to leave our home planet in a sustainable manner. The Model Implementation Agreement states that “Nothing in this Agreement or in the Treaty shall be interpreted as limiting the rights of individuals under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights or the formation of sovereign states by settlements under customary international law.” (Paragraph 10) Any international framework of laws must acknowledge and incorporate these protections, or it will fail.

The historical perspective

The early 21st century is an extraordinary time. Humanity has been presented with an historic opportunity as it prepares to leave its home planet. Like those who went forward during the Age of Exploration five centuries ago, the decisions we make today will affect humanity for centuries, perhaps millennia. If ever there has been a time to determine how to implement humanity’s collective vision for the future, it is now.

In October 1957, people all over the world stood outside their homes as the sun set, looking to the sky as a blinking light passed overhead, the tumbling upper stage booster of the world’s first satellite, Sputnik. Because of the Cold War there was some fear, but for most the overwhelming emotions were excitement, inspiration, and hope. Despite all its imperfections, all its follies, and all its deadly conflicts, humanity had managed to throw off the shackles of gravity and reach the stars. All the stuff of science fiction suddenly seemed possible. And not just the stuff about technology; the writers, the poets, those who dared to dream of a better future saw a day when humanity could resolve its differences by peaceful means and move forward together.

This dream was enhanced a decade later, in December 1968, when our view of the world literally changed. As Apollo 8 rounded the Moon, the astronauts on board were suddenly overwhelmed as humans saw the Earth rising above the lunar horizon for the first time. The picture taken at that moment showed our home planet, beautiful and fragile, hanging in the vastness of space. Humanity as a species began to realize that we are all one, living together on a small planet hurtling through the cosmos.[17]

But even though no borders were visible, war and suffering continue to wrack the home world. In the half-century since, people have begun to lose faith in their governments, their private institutions, even in humanity itself. Every day people wake up to news of the increasingly disastrous effects of climate change, racial and gender injustice, worsening economic inequality, and assaults on democracy. To that has now been added the threat of war in outer space. The people of Earth are beginning to despair, wondering if there is anything they can really believe in. They are losing hope, and the resulting cynicism is poisoning our politics, our relationships, even our thinking.

The mission of space law must be nothing less than to restore that hope, to inspire humanity by giving the people of our planet a future they can believe in. To counter the despair of war and violence and neglect. To build that shining city on a hill that will light the way for all.

The time to act

It has been more than 500 years since the world has had such an opportunity to start anew. At that time, European countries used their advanced technology to perpetuate military conquest and economic exploitation as they competed for resources, causing widespread misery and countless wars. And when the Industrial Revolution came along, governments placed profits ahead of people, resulting in economic and environmental catastrophe. By 2021, many people have stopped believing in their ability to control their own destiny, or humanity’s.

We can change that. We can avoid making the same mistakes. But doing so requires immediate action. There will be only one time when humanity leaves our home world, only one chance to create a new pattern that will lead each person, and all nations, to their best destiny.

It is time to share the Moon.

References

[1] E. Ostrom, Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. Nobel Prize Lecture, Dec. 8, 2009, 412-13. (grid copied verbatim). Full paper at American Economic Review, vol. 100, no. 3, 641-72 (June 2010).

[2] Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs, aka The Outer Space Treaty (1967).

[3] The Artemis Accords, NASA (2020).

[4] National Space Laws, United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs (2021).

[5] Agreement Governing The Activities Of States On The Moon And Other Celestial Bodies, aka the Moon Treaty (July 11, 1984). See also The Hague International Space Resources Governance Working Group, Building Blocks for the Development of an International Framework on Space Resource Activities (2019). “8. Resource rights 8.1 The international framework should ensure that resource rights over raw mineral and volatile materials extracted from space resources, as well as products derived therefrom, can lawfully be acquired through domestic legislation, bilateral agreements and/or multilateral agreements. 8.2 The international framework should enable the mutual recognition between States of such resource rights. 8.3 The international framework should ensure that the utilization of space resources is carried out in accordance with the principle of non-appropriation under Article II OST.” [emphasis added]

[5(a)] “Article 8

1. States Parties may pursue their activities in the exploration and use of the moon anywhere on or below its surface, subject to the provisions of this Agreement.

2. For these purposes States Parties may, in particular:

(a) Land their space objects on the moon and launch them from the moon;

(b) Place their personnel, space vehicles, equipment, facilities, stations and installations anywhere on or below the surface of the moon. Personnel, space vehicles, equipment, facilities, stations and installations may move or be moved freely over or below the surface of the moon.

3. Activities of States Parties in accordance with paragraphs 1 and 2 of this article shall not interfere with the activities of other States Parties on the moon. Where such interference may occur, the States Parties concerned shall undertake consultations in accordance with article 15, paragraphs 2 and 3, of this Agreement.

“Article 9

1. States Parties may establish manned and unmanned stations on the moon. A State Party establishing a station shall use only that area which is required for the needs of the station and shall immediately inform the Secretary-General of the United Nations of the location and purposes of that station. Subsequently, at annual intervals that State shall likewise inform the Secretary-General whether the station continues in use and whether its purposes have changed.

2. Stations shall be installed in such a manner that they do not impede the free access to all areas of the moon of personnel, vehicles and equipment of other States Parties conducting activities on the moon in accordance with the provisions of this Agreement or of Article I of the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies.”

[emphasis added]

[6] See, e.g., European Space Policy Institute, Artemis Accords: What Implications for Europe? ESPI BRIEFS No. 46, (Nov. 2020)

[7] Wikipedia, Svalbard Treaty. (Many thanks to Alex Gilbert, whose presentation on the Svalbard Treaty in February 2021 at the Commons in Space Conference provided the basis for this analysis. His work on outer space resources is also available here and here)

[8] International Organization for Standards (ISO).

[9] The Committee on Space Research (COSPAR).

[10] The Moon Village Association.

[11] For All Moonkind.

No comments:

Post a Comment