Since I was a young child Mars held a special fascination for me. It was so close and yet so faraway. I have never doubted that it once had advanced life and still has remnants of that life now. I am a dedicated member of the Mars Society,Norcal Mars Society National Space Society, Planetary Society, And the SETI Institute. I am a supporter of Explore Mars, Inc. I'm a great admirer of Elon Musk and SpaceX. I have a strong feeling that Space X will send a human to Mars first.

Monday, January 31, 2022

64 Years Ago Today The US Launched Its First Satellite Into Orbit

64 years ago, the US launched its first satellite into orbit around the earth. Explorer I was a small and slender tube with very primitive electronics. The rocket that launched it was a modified Redstone rocket that normally would have carried a nuclear warhead. It was what I call "a souped-up V-2" that was the brainchild of Dr. Werner von Braun. On top of that rocket was a cylinder full of small rocket motors that carried the satellite into orbit. This had been designed and developed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

There are many ironies and "might

have beens" in history. This satellite was ready to go and could have been

launched in 1956, a full year before the Soviets launched Sputnik on October 4,

1957.

Dwight D. Eisenhower was president at that

time. He had graduated from West Point in 1915. He never commanded men in

battle. He spent a good part of his career as a staff officer. When World War

II started, he was a major. By the time World War II ended, he had risen in the

rank of 5-star general and Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe. One

would expect such a man to be a big fan of the military. In reality, he was

quite skeptical of anything military. He saw the Redstone rocket as sending a

signal to the world that the US was going to militarize space.

Eisenhower opted for the Vanguard rocket

to be the launch vehicle for the first US satellite. Never mind that it was

sponsored by the US Navy. It was a launch system built solely for space

exploration. It had no military use.

The problem is that the Vanguard rocket

had many launch failures. After Sputnik was launched, a wave of hysteria swept

the US. In desperation, Eisenhower agreed to let the US Army launch Explorer I.

It worked right the first time.

Saturday, January 29, 2022

Friday, January 28, 2022

Wednesday, January 26, 2022

Tuesday, January 25, 2022

Monday, January 24, 2022

Becoming Off Worldly-How To Prepare To Be A Civilian Astronaut

|

Review: Becoming Off-Worldly

by Jeff Foust

Monday, January 24, 2022

Becoming Off-Worldly: Learning from Astronauts to Prepare for Your Spaceflight Journey

by Laura Forczyk

Astralytical, 2022

paperback, 255 pp.

ISBN 978-1-7344622-2-7

US$19.99

Last year finally opened the doors of the space tourism market, after years, if not decades, of anticipation. Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic flew people suborbitally, while SpaceX performed its first commercial Crew Dragon flight to orbit. Even the Russians got back into the space tourism business, flying commercial customers to the International Space Station on Soyuz spacecraft for the first time in more than a decade. More private astronauts are set to fly this year, with Blue Origin expected to conduct several crewed New Shepard flights and Axiom Space sending its first customers to the ISS on a Crew Dragon launching at the end of March.

More opportunities for non-professional astronauts to go to space mean more people will be looking for insights into what the spaceflight experience is like. The new book Becoming Off-Worldly by Laura Forczyk, founder of the space consulting firm Astralytical, attempts to fill that gap by talking to both private and government astronauts about what it was like to travel to space as well as train for those flights.

| “I’m not going to sugarcoat it: wealth or connections will give you a leg up. At least for now.” |

As with her earlier book on the perceptions millennials have about space (see “Review: Rise of the Space Age Millennials”, The Space Review, February 10, 2020), Forczyk uses extensive interviews as the foundation for Becoming Off-Worldly. These interviews are with former government astronauts (and one current one, ESA’s Samantha Cristoforetti) as well as private individuals who have flown in space or who are planning to fly, or are otherwise involved in commercial spaceflight. As it turns out, there is some overlap between the groups: former NASA astronaut Michael López-Alegría is set to command Axiom’s Ax-1 mission launching to the ISS in March, while another former NASA astronaut, Nicholas Patrick, is now involved with Blue Origin’s New Shepard program.

Some of the chapters of the book discuss the spaceflight experience itself: the acceleration of liftoff, the sensations of microgravity, and the change in mindset created by seeing the Earth from space. Richard Garriott de Cayeux, who flew to the ISS on a Soyuz mission in 2008, recalled the experience of seeing where he lived in Austin, Texas, and where he grew up in Houston, in the same field of view from the station. “Suddenly, I had a deep reaction that was both mental and physical,” he recalled. “In this case, the Earth obviously stayed the same size out the window, but my conception of its scale immediately and radically diminished.”

Other chapters of the book examine the training and other preparation, physical and mental, associated with spaceflight. Private astronauts can come from a much broader range of backgrounds than professional government astronauts, but can still benefit from both advance planning for their flights—especially for suborbital missions that last only minutes—as well as physical preparation. There’s also the financial issue, she acknowledges. “I’m not going to sugarcoat it: wealth or connections will give you a leg up. At least for now.”

Forczyk makes clear she is not a dispassionate observer of the field: she wants to go herself, and has done training such as parabolic aircraft flights and centrifuge runs to prepare for a trip, some day. “Writing this book while cheering on the commercial spaceflight accomplishments of 2021 has given me new hope for my own personal goal of personal spaceflight,” she writes.

For those who became curious about the prospects of flying into space because of those accomplishments last year, Becoming Off-Worldly is a good place to start. It won’t tell you everything you need to know before signing up and paying a deposit, but will help you better appreciate what to expect and help decide if it’s really for you.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

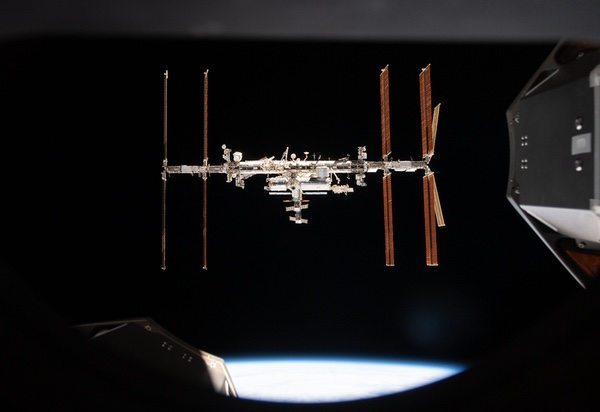

Space Policy, Geopolitics and the ISS

The International Space Station as seen bya departing Crew Dragon spacecraft in November. The international partnership that made the station possible is facing its strongest geopolitical challenge to date as Russia threatens to invade Ukraine. (credit: NASA) |

Space policy, geopolitics, and the ISS

by Jeff Foust

Monday, January 24, 2022

On the International Space Station, it is business as usual these days for the seven-person multinational crew. A Dragon cargo spacecraft undocked from the station Sunday, returning experiments and other equipment to Earth after a month-long stay. Last week, the station’s two Russian cosmonauts, Anton Shkaplerov and Pyotr Dubrov, spend seven hours outside the station on a spacewalk working on the Prichal module, added to the Russian segment of the station in November. That spacewalk was covered live on NASA TV, much like those involving NASA and other western astronauts.

| Biden said that while he didn’t think Putin had decided yet to invade, he expected Putin to do so. “My guess is he will move in. He has to do something.” |

It is not, though, business as usual down on Earth when it comes to Russia’s relationship with the US and the West. For months, there have signs that Russia was massing troops for an invasion of Ukraine this winter. Those concerns have grown ever stronger to the point where some believe an invasion is all but inevitable.

“Do I think he’ll test the West, test the United States and NATO as significantly as he can?” President Joe Biden said at a January 19 press conference, referring to Russian president Vladimir Putin. “Yes, I think he will.” He added later that while he didn’t think Putin had decided yet to invade, he expected Putin to do so. “My guess is he will move in. He has to do something.”

An invasion in the coming weeks would come nearly eight years after Russia entered eastern Ukraine and annexed Crimea. The stakes, though, are higher this time. “This will be the most consequential thing that’s happened in the world, in terms of war and peace, since World War II,” Biden said.

For the space community, the prospect of a Russian invasion of Ukraine raises questions about the future of cooperation between Russia and the West in space, particularly on the International Space Station. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 prompted sanctions by the West. In response, Dmitry Rogozin, then deputy prime minister, threatened to cut off the supply of RD-180 engines used by the Atlas 5 as well as deny NASA astronauts seats on Soyuz flights to the ISS—infamously suggesting that NASA would have to rely on a trampoline to get to the station.

Russia, though, never followed through on those threats: the RD-180 engines kept coming and NASA astronauts kept flying on Soyuz missions. This time around, officials in the US and Europe are trying to look beyond the tensions on the ground as they look to maintain their partnerships with Russia in space.

NASA administrator Bill Nelson, for example, has frequently emphasized the longstanding partnership between the US and Russia in space, one that he argues stretches back to the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975. “NASA is in contract with our Russian colleagues all the time because, as you know, we operate the International Space Station together,” he said in a media call January 11 to introduce a new chief scientist for the agency.

He's frequently talked about going to Russia to meet with Rogozin, who is now the head of Roscosmos. (Rogozin cannot come to the United States because of sanctions that stem from his role in the events of 2014.) In the call earlier this month, he reiterated his plans to do so, with Covid playing a bigger factor than a potential invasion of Ukraine.

“I am simply at the mercy of Covid, and until we see a subsiding of this pandemic, I’m not going to be able to go,” Nelson said. “I’m looking forward to personally meeting Dmitry, and in the meantime we’ll continue to talk as frequently as need be.”

| “We want to separate cooperation in space from the bigger political picture on the ground,” Aschbacher said. |

The European Space Agency has to contend with not just potential disruptions with the ISS in the event of a Russian invasion of Ukraine, but also European-Russian partnership on a Mars mission. ExoMars is scheduled to launch in late September on a Proton rocket, carrying the ESA-built Rosalind Franklin Mars rover that will be delivered to the surface of Mars on a Russian platform called Kazachok. That mission was to launch in mid-2020 but missed its launch window because of technical problems exacerbated by the onset of the pandemic.

At a January 18 press conference, Josef Aschbacher, director general of ESA, was not concerned about geopolitics interfering with ExoMars or the ISS. “We want to separate cooperation in space from the bigger political picture on the ground,” he said. “I certainly believe that what happens politically on the ground will not change of the plans towards the launch” of ExoMars.

“The space station is the best symbol of working together because we rely on each other and we need each other, especially for big undertakings,” he added. “I do, honestly, want to underline that in space we do need a long-term cooperation. We need all the forces of space agencies worldwide.”

The terrestrial tensions complicate what is a key time for the ISS. On New Year’s Eve, the White House announced it supported an extension of the ISS through 2030, compared to the “at least 2024” date in current federal law. The announcement was not a surprise—NASA’s long-term ISS plans, and efforts to support development of commercial successors, expected the ISS to keep operating through the end of the decade—but still kicked off formal planning to extend the station’s life.

Immediate after the NASA announcement, ESA’s Aschbacher endorsed the extension, saying he will ask the agency’s member states to back ESA’s participation in the station through 2030, likely at the next ministerial meeting late this year. Canada and Japan are also likely to follow along.

“We’re very happy to see the announcement from the U.S. side. That’s helping the decision process,” said Christian Lange, director of space exploration planning, coordination, and advanced concepts at the Canadian Space Agency, during a panel discussion at the AIAA SciTech Forum January 6. “No one would have expected Canada to make a decision before the U.S. or even ESA or Roscosmos.”

“We were seeking the trigger by NASA to extend the ISS beyond 2024,” said Naoki Sato, exploration lead at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, on the same panel. “With that trigger, we have just started the discussion for the extension of the ISS.”

Roscosmos, though, has not discussed its intentions about extending the ISS since the White House announcement. In recent months, Rogozin has been dismissive about a long-term extension because of what he said was the growing technical challenges of maintaining the aging station.

“The current agreement is that we’ll keep operating it until 2024. It can, of course, keep flying after 2024, but every next year will come at greater difficulty,” he said during a press conference at the International Astronautical Congress (IAC) in Dubai in October.

| A State Department spokesperson declined to discuss details about a cosmonaut’s denied visa but added that “the United States values the important bilateral cooperation on the International Space Station.” |

There has been greater progress on a near-term issue that ties the US and Russia closer together on the ISS: swapping seats between Soyuz and commercial crew vehicles. NASA has advocated for a barter agreement that would allow NASA astronauts to continue to fly on Soyuz spacecraft in exchange for Russian cosmonauts flying on Crew Dragon and, eventually, CST-100 Starliner vehicles. Such “mixed crews” would ensure at least one NASA and one Roscosmos crewmember would be on the station in the event either Soyuz or commercial crew vehicles were unavailable for an extended period.

While NASA pushed for a barter agreement, Roscosmos was initially opposed, arguing that the commercial crew vehicles were not yet proven. However, at the IAC in October, Rogozin said he was now satisfied. “In our view, SpaceX has already acquired enough experience for us to be able to put our cosmonauts on Crew Dragon,” he said.

The seat barter agreement is in the process of being approved by the American and Russian governments. At a meeting last week of a NASA Advisory Council committee, Robyn Gatens, ISS director at NASA headquarters, said the agreement had completed a review by Roscosmos and was now in the hands of the Russian foreign ministry.

The goal is to have the deal completed in time to allow a seat exchange this fall. Roscosmos announced in December that cosmonaut Anna Kikina would go on the Crew-5 Crew Dragon mission to the ISS, while NASA astronaut Frank Rubio is likely to go on Soyuz MS-22.

A backup cosmonaut for Soyuz MS-22 is Nikolai Chub, who is scheduled to go to the station on the Soyuz MS-23 mission next year. However, Roscosmos announced over the weekend that the US government denied Chub a visa to come to the US for routine training at the Johnson Space Center intended to familiarize Russian cosmonauts with the US segment of the station.

Rogozin told Russian media, and stated in his own social media postings, that he would ask NASA why Chub was denied a visa. The US State Department declined to comment on the issue, noting that via records are confidential under US law. A spokesperson added, though, that “the United States values the important bilateral cooperation on the International Space Station.”

The timing of the visa incident, though, can’t help with either near-term or long-term relations between NASA and Roscosmos on the ISS, or other aspects of international partnership, as geopolitical tensions grow. The State Department over the weekend recommended that Americans not travel to Ukraine, and that Americans currently in the country leave.

Even if the ISS is unaffected by any repercussions from a Russian invasion of Ukraine and responses by the US and other countries, it doesn’t mean space policy won’t be altered. While Russia never followed through on threats to cut off shipments of RD-180 engines, the threat, coming at the same time as SpaceX was suing the US Air Force to win the right to bid on national security launches, reshaped the US government launch market. SpaceX secure the right to compete for military launches and ULA, knowing the RD-180 supply would be shut off sooner or later, moved forward with Vulcan.

The threat of losing access to Soyuz seats, and thus the ISS, helped remove any remaining doubts about the commercial crew program. When SpaceX launched the Demo-2 mission in May 2020 with two NASA astronauts on board to the ISS, it was Elon Musk who said at a post-launch press conference, “The trampoline is working!”

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Sunday, January 23, 2022

Tuesday, January 18, 2022

Monday, January 17, 2022

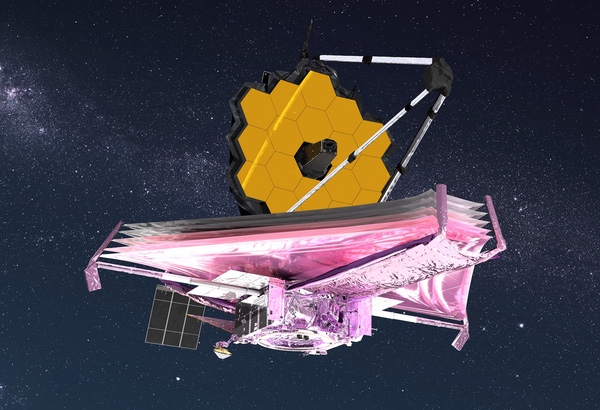

The James Webb Telescope-Not Yet Imagined

|

Review: Not Yet Imagined

by Jeff Foust

Monday, January 17, 2022

Not Yet Imagined: A Study of Hubble Space Telescope Operations

by Christopher Gainor

NASA, 2021

ebook, 452 pp., illus.

free

The James Webb Space Telescope is, in many respects, unlike any other astrophysics mission launched to date: a massive telescope that required an intricate series of deployments after launch last month to take its final shape, with months of commissioning of its mirrors and instruments still ahead, all to peer deeper into the universe than any previous observatory. Yet, it’s based on the legacy and the institutions of its predecessors, notably the Hubble Space Telescope.

That legacy is examined in Not Yet Imagined, a book from NASA’s history office about the operations of Hubble. Historian Christopher Gainor examines Hubble after its 1990 launch through nearly the present day, a three-decade span with both setbacks and major accomplishments scientifically and technically.

| Gainor estimates that the full cost of Hubble, including operations and the shuttle missions to launch and service it, is around $20 billion in present-day dollars. |

Gainor summarizes the long development of Hubble in an introductory chapter before turning his attention to its operations after launch, starting with the realization just a couple months later that the telescope’s primary mirror had been improperly shaped, a blow not just to astronomers but also to the agency’s reputation. That led to efforts to develop corrective optics installed on a December 1993 servicing mission that repaired the telescope as well as public perceptions of NASA.

Three more servicing missions followed through 2002, replacing instruments and making other improvements to Hubble. Planning was underway for a fifth servicing mission, and even consideration of a sixth, when the Columbia accident took place in 2003, grounding the shuttle fleet. NASA’s leadership decided a year later to abandon plans for that fifth servicing mission because of the risks involved, a move that generated professional, political, and public efforts to overturn it. After studies of a potential robotic servicing mission, a new NASA administrator, Mike Griffin, restored that shuttle servicing mission, which flew in 2009.

Besides the series of shuttle servicing missions, Gainor examines the more routine operations of the observatory, from the process of applying for telescope time to how the observations take place and the data placed into the hands of astronomers. He also examines the roles of institutions like NASA and the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), which handles the science operations of Hubble (and also JWST), play in Hubble. That extends to issues such as diversity in the field of astronomy: STScI hosted a conference on women in astronomy in the early 1990s that led to the “Baltimore Charter” of recommendations to improve the status of women in the field, yet the institute itself later had problems attracting and retaining female staff.

One question that the book takes on is the value of Hubble. Gainor estimates that the full cost of Hubble, including operations and the shuttle missions to launch and service it, is around $20 billion in present-day dollars. That is a lot of money, albeit spread out over several decades, but Hubble has become over that time the world’s most famous telescope. Data from the telescope has been used in more than 16,000 scientific papers as of 2019, he notes. It also helped build support not just for future space telescopes like JWST but also the International Space Station: the success of the 1993 servicing mission, with a series of complex spacewalks to repair the telescope, provided reassurances to NASA and the White House that the space station was feasible. Hubble and its images have become cultural touchstones, which could explain the outpouring of support when NASA said it would cancel the fifth servicing mission. Compare that to the ridicule it faced in the early 1990s: Gainor notes that, in the 1991 comedy The Naked Gun 2½, a picture of Hubble was on the wall of a bar along with notable disasters like the Titanic and the Hindenberg.

| Astronomers remain hopeful Hubble can keep operating through the middle of the decade and beyond. That is a longevity that, when the mission was originally designed with a 15-year life, could not be imagined. |

Some of the lessons from Hubble won’t be directly applicable to JWST. A key one is servicing: while Hubble’s life was extended, and its capabilities increased, with servicing, JWST is on its own at the Earth-Sun L-2 point, 1.5 million kilometers away. (There had been some discussion before the launch of a robotic refueling mission for JWST, but the precise Ariane 5 launch, saving fuel for stationkeeping that could double its life, may but the brakes on that.) But JWST will take advantage of the science and operational lessons of Hubble, and even some lessons from Hubble’s commissioning. In 1990, NASA officials agreed to release first images from Hubble as soon as possible, but JWST officials say they’ll hold off on showing those first images until the commissioning is complete months from now. One reason for doing so, a project scientist said at a briefing earlier this month, is that it will take a lot of work to align JWST’s mirrors; those first images “will be ugly.”

Hubble itself continues. The telescope remains in remarkably good condition despite being more than a dozen years since the final servicing mission. While it has encountered a number of technical problems in recent years, engineers have been able to restore full operations and astronomers remain hopeful Hubble can keep operating through the middle of the decade and beyond. That is a longevity that, when the mission was originally designed with a 15-year life, could not be imagined, much like its scientific and broader legacy.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Saturday, January 15, 2022

Friday, January 14, 2022

Thursday, January 13, 2022

Wednesday, January 12, 2022

162172 Ryugu-Primordial Rock

Primordial Rock

In 2019, Japan’s Hayabusa2 asteroid explorer collected samples from the near-Earth asteroid Ryugu – scientifically known as 162172 Ryugu.

Following the probe’s return in December 2020, scientists have thoroughly examined the space dust it collected to learn more about the asteroid’s composition, Smithsonian Magazine reported.

Astronomers have particularly focused on Ryugu because the space rock has remained unchanged since the solar system’s formation some 4.5 billion years ago.

In one study, a research team analyzed the 5.4-gram sample and found that Ryugu has minerals and compounds previously seen in other meteorites on Earth. However, they also documented the presence of organic and water-bearing molecules. Among them were volatiles such as hydroxyls – made of oxygen and hydrogen atoms – which most likely originated in the outer solar system.

In the second study, researchers led by Toru Yada discovered that the celestial body is so dark that it only reflects two to three percent of the light that hits it. Their results also showed that Ryugu was 50 percent more porous than other carbonaceous meteorites that hit Earth.

Both papers also confirm that the celestial body is carbonaceous – meaning rich in carbon – and should be classified as a CI chondrite. These types of meteorites have a composition very similar to that of the solar photosphere, which means they are the most primitive of all known space rocks, according to Science Alert.

Despite the fascinating findings, the authors noted that there is more to learn about the celestial body, including its age and when it encountered water.

They also hope that further research could provide new clues about how the solar system formed.

C

Tuesday, January 11, 2022

Steady Growth Beyond The Skies- Ficve Trends In Outer Space From 2021

SpaceX launched 31 Falcon 9 rockets in 2021, part of a worldwide surge in orbital launch activity last year. (credit: SpaceX) |

Steady growth beyond the skies: five trends in outer space from 2021

by Harini Madhusudan

Monday, January 10, 2022

Outer space was one of the most successful domains in 2021 amidst fluctuations in politics and industry worldwide. The world observed dynamic growth in space, specifically in the participation of non-state players, while among the government players there was significant institutionalization. There were an estimated 141 orbital launches in the year with 132 successes and up to ten missions that were related to various planetary achievements. The 2020s have seen a significant increase in investment in space, and many of the missions undertaken in the past decade have come to fruition in the past two years. These achievements individually have added a lot of value and have set the ball rolling for a Space Race 2.0. This time, it includes many more contenders than the US or the former USSR, and have expanded to include major corporations competing at an unprecedented scale. What are the highlights of space activities in 2021?

| In recent years, the private sector have shown significant capabilities and constantly engaged with the governments, changing the way one would look at space. |

The year saw a consistent growth in many space sectors, including many anticipated technologies and missions. The growth in space have been both horizontal and vertical. As the world saw the impressive display of new technologies, it also witnessed relatively new players achieve significant goals. Humankind once again outdid itself by venturing further and achieving deeper knowledge of the domain while also reducing costs and working towards the sustainable futures of the investments made for space.

In recent years, the private sector have shown significant capabilities and constantly engaged with the governments, changing the way one would look at space. Simultaneously, a coalition of Russia and China announced combined activities related to joint missions, including their intention of setting up a Moon base, the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), for scientific purposes. This can be viewed as their response to the Artemis Accords of 2020. In 2021, China conducted more orbital launches than the US, while Russia stands third in the number of orbital launches. Myanmar, Tunisia, Kuwait, Paraguay, and Moldova are some of the new entrants who launched their first satellites during the year. Additionally, this year marked the presence of the highest number of humans (after 2009) at a time beyond the atmosphere, with 16 people.

With the coming year set to be filled with much more expansive activities, beginning with the Artemis 1 mission, Europe and Russia aiming to send a rover to Mars, testing of new rockets, and NASA’s DART mission crashing into an asteroid, here is a look at the five trends that have shaped space activities in the last year.

Private industry competition: SpaceX is the most popularly known private player in space. There has been a steady growth in investment in private space companies and many of those displayed their capabilities during 2021. Three prominent among tourist missions in 2021 were suborbital tourist flights by Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin and SpaceX’s orbital tourist flight. The year also saw Axiom Space getting approval to send private astronauts to the International Space Station. Many private companies are involved in preparing and launching small satellites and satellite constellations serving various industries, while new companies offer in-situ service abilities and satellite longevity services, which are great for reducing the burden on the government investments.

Solar system exploration: The year began with the successes of three Martian missions by the US, UAE, and China, each mission with unique goals. That includes the Ingenuity helicopter technology demonstration that is part of NASA’s Perseverance mission. A second successful mission would be the Parker Solar Probe, which became the first spacecraft to pass through the Sun’s corona last year. In October, NASA’s Lucy mission launched on a mission to explore Jupiter’s Trojan asteroids and study the evolution of the solar system.

Space Race 2.0: There is a space race brewing, as seen by the technological competition and the political intention of the countries with significant space capabilities. This year saw intense competition between the space powers of Russia, the US, and China. Though the Chinese have matched or surpassed the US in technological capabilities in certain sectors like a hypersonic vehicle test or with their space station, the Chinese still have a long way to catch up with the US technological strengths overall. However, the Chinese space capabilities and its steady growth in space can be seen as a threat to the US dominance in space. Certainly, US space capabilities are branching out into myriad private companies, which have reduced the burden of investments by the state.

| Private industry is likely to expand at a very fast pace. Considering the alarming absence of regulatory systems, the coming years should lead to calls for more efforts by nations to address this vacuum. |

Three incidents from 2021 can be considered as indicators of the space race. One is the ASAT test by Russia in November. The second is the Chinese display of hypersonic capabilities, which they claimed were for their satellite launches. The third, arguably, is the US DART mission, which shows capabilities for planetary defense that could potentially be used against adversaries when needed. Additionally, there have been instances between the US and China of blaming each other’s activities as a threat to their own. These include US complaints of the impact of the falling booster that launched a Chinese space station module and the Chinese complaints to the UN against SpaceX. The Russian ASAT test was extensively criticized for the debris that it generated. Russia and China, meanwhile, continued working with each other in their space activities.

Technological milestones: SpaceX’s Falcon 9 completed 31 orbital flights just in 2021, and the company also marked the 100th landing of a rocket. The long-awaited launch of the James Webb Space Telescope and its subsequent, flawless deployment is another major space technology milestone. The space debris problem is the focus of multiple cleanup missions, such as Astroscale’s ELSA-d, which demonstrated a magnetic capture system in August.

Space tourism: Space tourism was one of the highlights of 2021. Many private companies marked the beginning of their tourism services. The CEOs and public faces of some of these companies went on their first flights. It is significant to know that most of these private individuals were untrained civilians flying beyond the atmosphere, either to orbit or on a suborbital mission. In addition, a crew from Russia flew to the ISS to shoot a movie. These missions have included a diverse group of individuals ranging from a cancer survivor to the first Black woman pilot, performing diverse activities such as painting or photography.

These trends are expected to continue in the coming year. Private industry is likely to expand at a very fast pace. Considering the alarming absence of regulatory systems, the coming years should lead to calls for more efforts by nations to address this vacuum. Interesting times lie ahead.

Harini Madhusudan is a doctoral scholar at the School of Conflict and Security Studies of the National Institute of Advanced Studies in India.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new accou

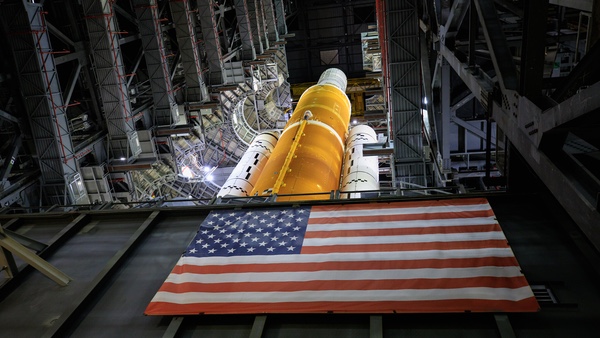

New Year, New ANd Overdue Rockets

The first SLS in the Vehicle Assembly Building at the Kennedy Space Center, awaiting a first launch some time in 2022. (credit: NASA/Frank Michaux) |

New year, new (and overdue) rockets

by Jeff Foust

Monday, January 10, 2022

In a race to see which will launch first, neither the Space Launch System nor Starship appears to be winning.

Both giant launch vehicles are set to make their first launches early this year. In the case of SLS, that launch comes after years of delays that have had ripple effects on the overall Artemis program. SpaceX’s Starship had also fallen behind the aspirational schedules of its founder, Elon Musk, who in September 2019 predicted that the company would “try to reach orbit in less than six months” (see “Starships are meant to fly”, The Space Review, September 30, 2019).

| However, it wasn’t clear that SpaceX would have been ready for an orbital Starship launch in January or February even if the FAA issued a launch license at the end of December as Musk anticipated. |

Late last year, both NASA and SpaceX said they were ready for inaugural launches of their vehicles in early 2022. In October, NASA officials announced they were targeting no earlier than February 12 for the SLS launch of Artemis 1, an uncrewed test flight of the Orion spacecraft. A month later, Musk told two National Academies committees that he expected the first Starship/Super Heavy orbital flight to take place “in January or perhaps February,” assuming SpaceX got a launch license from the FAA by the end of December.

Neither vehicle is launching in January or February, though. In mid-December, NASA announced that an engine controller, a computer that controls the RS-25 engines in the core stage of the SLS, was malfunctioning: one of two redundant channels in the controller “failed to power up consistently.” After weeks of troubleshooting, NASA decided to replace the controller while it continued to study the problem. That would rule out a launch in February: the agency said it was “reviewing launch opportunities in March and April.”

Even those launch opportunities remain in doubt. On Wednesday, NASA said it was preparing to roll out the vehicle to Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 39B in mid-February for a fueling test and simulated countdown known as a wet dress rehearsal. “NASA will set a target launch date after a successful wet dress rehearsal test,” the agency stated. But given the time needed to perform the test, then roll the SLS back to the Vehicle Assembly Building for final preparations before going back out to the pad, a launch even in April starts to look doubtful.

Halfway across the country in Boca Chica, Texas, regulatory issues have put the brakes on Musk’s schedule for launching Starship. The FAA did not award SpaceX a launch license for Starship at the end of December, instead announcing that it needed at least two more months to complete a controversial environmental review (see “The battle for Boca Chica”, The Space Review, October 25, 2021).

Part of the reason the FAA gave for the two-month extension was that SpaceX still had to address more than 18,000 public comments submitted regarding the draft version of the environmental review. That suggested to some that SpaceX’s more strident fans, who spoke out in support of the company at two public hearings, might have undermined the company’s plans with their outpouring of support. However, the FAA also said that it was continuing the consultation process with other agencies for the environmental review, particularly involving endangered species and preservation of historical sites.

There is no guarantee that the FAA will be ready at the end of February, its new deadline for completing the environmental review. An environmental review for Spaceport Camden, a proposed launch site in Camden County, Georgia, suffered extensive delays in its environmental review, including a series of shifting deadlines before the FAA awarded a license to the spaceport last month.

However, it wasn’t clear that SpaceX would have been ready for an orbital Starship launch in January or February even if the FAA issued a launch license at the end of December as Musk anticipated. He said in November there would be a “bunch of tests” in December, but there were only a handful of tanking and static fire tests of Starship, and much less testing of the Super Heavy booster. A delay in FAA licensing could provide cover for any technical delays, or the company may simply be slowing down work knowing the vehicle doesn’t need to be ready until at least March.

Arianespace’s CEO is confident the first Ariane 6 will launch before the end of 2022. (credit: ESA/D. Ducros) |

Other new launchers

A few years ago, 2020 was shaping up to be a milestone year for new launch vehicles. Four new vehicles intended, at least in part, to serve commercial markets were scheduled to make their inaugural launches that year: Arianespace’s Ariane 6, H3 from Japan’s Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI), Blue Origin’s New Shepard and the Vulcan Centaur by United Launch Alliance.

As of the end of 2021, those four vehicles have, combined, a perfect track record: zero for zero. All four vehicles have suffered development delays that pushed back their first launches to 2021 and now to 2022 or later.

| “Absolutely not 2023,” Peller said when asked if early 2023 was a likely date for the first Vulcan launch. “We have a plan that will support a flight in mid-2022.” |

Heading into 2022, some companies are confident that this will be their year their vehicles make their first launch. At a press briefing last week, Arianespace CEO Stéphane Israël said his company was expecting to launch the first Ariane 6 in the second half of the year. He noted that the core and upper stages of an Ariane 6 were being shipped to the launch site in French Guiana for tests on the launch pad there starting in April, including a hotfire test of the core stage.

He said he was confident that, despite numerous schedule slips, including one recently from the second quarter to the latter half of 2022, the rocket would take flight before the end of the year. “All our energies are mobilized to do so,” he said at the briefing. “Very important milestones are now behind us, and this is why we are confident of making this maiden flight this year.”

A few weeks earlier, he had similar confidence in an Ariane 6 launch in 2022. “There will be no delay in Ariane 6 because we are now in the very last mile leading to the launch,” he said during a panel discussion at Euroconsult’s World Satellite Business Week in Paris in mid-December.

At the same panel, a ULA executive offered similar confidence in the schedule for Vulcan Centaur. The key issue for that vehicle has been delays in the development of the BE-4 engine by Blue Origin and thus delivery of those engines to ULA.

“The Blue team is making great progress and we do expect to receive those engines some time in the first quarter of this coming year,” said Mark Peller, vice president of major development at ULA, during the December 2021 panel. “That puts us on a good pace to get the integrated rocket down to the launch site and supporting an inaugural launch for Astrobotic’s Peregrine lunar lander” in 2022.

Some are skeptical that the Vulcan can be ready if the first flight-ready BE-4 engines don’t arrive until as late as early spring, but Peller was adamant that the first Vulcan could instead launch as soon as the summer. “Absolutely not 2023,” he said when asked if early 2023 was a likely date for the first launch. “We have a plan that will support a flight in mid-2022.”

Neither MHI nor the Japanese space agency JAXA have provided many updates on the status of the H3, other than past schedules that suggested a first launch as soon as the first quarter of this year. Blue Origin, meanwhile, made it clear that a first launch of New Glenn in late 202, a date it set early last year, was looking increasingly unlikely.

“Yes, we have a target to launch, but we will launch when we’re ready and we are aligned with our customers,” Jarrett Jones, senior vice president for the New Glenn launch vehicle program at Blue Origin, said at the panel last month.

The company was moving ahead with testing and qualification of various components of the vehicle, he said. “My expectation is that qualification will be completed next year and that we will have a rocket in build, if not built, by the end of the year, ready for launch,” he said.

New Glenn, like Vulcan, uses BE-4 engines, although with seven in its first stage versus two BE-4 engines for Vulcan. “The expectation is that we’ll get those towards the second half of 2022,” Jones said of the first flight-ready BE-4 engines, “and then we’re going to need three months for integration.”

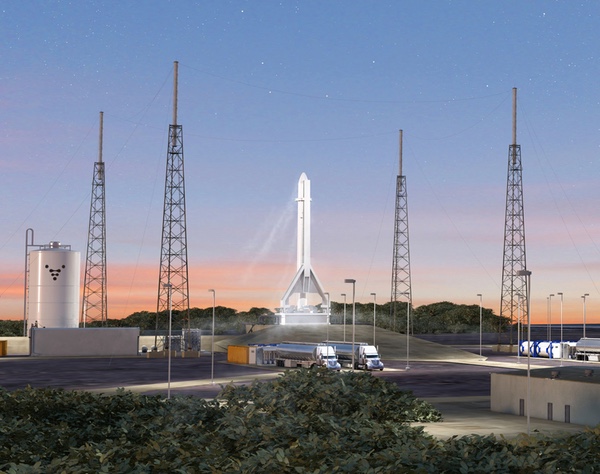

Relativity Space says it’s a “few months” away from the first launch of its Terran 1 rocket. (credit: Relativity |

New small launchers

Last year saw the successful introduction of new small launch vehicles, including Astra’s Rocket 3.3 and Virgin Orbit’s LauncherOne. Both vehicles are scheduled for launches this month, with LauncherOne flying as soon as Wednesday from the Mojave Air and Space Port in California and Astra launching a set of cubesats for NASA from Cape Canaveral, Florida.

Those two companies, along with Rocket Lab, are just a few at the forefront of a field with dozens of small launchers in development. Some of those vehicles, by companies from Europe to China to the United States, are planning their first launches in 2022.

| “We’re doing our first launch in a few months from our launch site at Cape Canaveral,” said Relativity’s Ellis. |

One company that will be launched closely is Relativity Space. The company has raised more than $1 billion since the fall of 2020, including a $650 million round in June. It used that round to announce its plans to develop a large reusable launch vehicle, Terran R, capable of placing up to 20,000 kilograms into low Earth orbit, with a first launch projected for as soon as 2024.

First, though, is the Terran 1, the company’s original vehicle and its entrant into the small launcher market and making extensive use of 3D-printing technologies. That vehicle, too, once has a goal of launching in 2020 but saw its launch slip to 2021 and now some time in 2022.

“We’re doing our first launch in a few months from our launch site at Cape Canaveral,” Tim Ellis, CEO of Relativity, said on another panel at World Satellite Business Week last month.

However, there’s still a lot of work ahead for Relativity before the first Terran 1 is ready for launch. He said the company was finishing up qualification of the Aeon engines used on the vehicle and completing acceptance testing of the primary structures of the vehicle. “We’re putting the finishing touches on the launch site right now,” he said, along with shipping the completed stages there. “Then we’ll be gearing up for first launch.”

He declined, though, to give a more specific date for that first launch than a few months. “You’ll see stuff soon,” he promised. Many companies have made similar statements; time will tell which will follow through this year.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Sunday, January 9, 2022

Saturday, January 8, 2022

Friday, January 7, 2022

Wednesday, January 5, 2022

Tuesday, January 4, 2022

The James Webb Space Telescope-Transfer of Tension

Transfer of tension

by Jeff Foust

Monday, January 3, 2022

Sure, the James Webb Space Telescope was launching on a rocket with an excellent track record, one that hadn’t suffered a catastrophic failure in nearly two decades. It didn’t mean people weren’t nervous when that rocket finally lifted off on Christmas morning.

Engineers who spent many years building JWST watched with astronomers who planned to spend many years using the space telescope. Years of work and billions of dollars were on the line, as well as the future of space-based astronomy. No pressure.

| “Generally speaking, the launch is of the order of 80% of the risk in a mission. I would say that… here it may be 20% or the risk, perhaps 30%,” said Zurbuchen. |

So, from the moment the Vulcain 2 engine in the core stage of the Ariane 5 ignited, followed seconds later by the two solid rocket boosters—the point of no return for the launch—they held their breaths. Their handiwork, and their futures, were in the hands of that rocket.

Twenty-seven minutes later, they could exhale. Right on schedule, JWST separated from the upper stage, bound for the Earth-Sun L-2 Lagrange point 1.5 million kilometers away. A camera on the upper stage captured the release of the telescope and, in a pleasant surprise, the deployment of the spacecraft’s solar array, which took place several minutes ahead of schedule. (NASA later said that the solar array was designed to deploy 33 minutes after liftoff or when it achieved a specific attitude, whichever came first; the accuracy of the launch meant it reached that deployment attitude early.)

Liftoff of the Ariane 5 carrying the James Webb Space Telescope. (credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls) |

“What we know now is that the injection was really perfect,” said Arianespace CEO Stéphane Israël at a briefing shortly after the launch. “It will help to have more lifespan for Webb.”

The accurate launch helps extend the lifespan of JWST by reducing the amount of propellant it needs to correct its orbit before arriving at L-2 29 days after launch. That conserves propellant for later stationkeeping maneuvers to maintain its halo orbit around L-2. In a December 29 statement, NASA said the propellant savings should support operations “for significantly more than a 10-year science lifetime,” but was not more specific.

But for JWST, the concern was never primarily about the launch. Instead, it’s what has to happen in the weeks after launch, as the telescope deploys major structures, notably its sunshield and mirrors. That will be followed by several months of commissioning of the telescope and its instruments as they cool to their operating temperatures a few dozen kelvins above absolute zero (see “For JWST, the launch is only the beginning of the drama”, The Space Review, December 20, 2021).

“Generally speaking, the launch is of the order of 80% of the risk in a mission. I would say that, by our analysis, by various ways of assessing that, here it may be 20% or the risk, perhaps 30%,” Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA associate administrator for science, said at that post-launch briefing. “We have retired quite some risk, but what is ahead remains is risk that we’re going to take down step by step.”

Those steps, at least initially, appeared to go according to plan. Key deployments like the spacecraft’s high-gain antenna, as well as the first two trajectory correction maneuvers, went as expected before controllers focused on the various steps in deploying the sunshield and stretching its five aluminum-coated Kapton layers into place, a process known as tensioning.

In a series of blog posts—NASA’s primary means of communicating updates on the mission in lieu of media briefings or other coverage—the agency stated that the deployment was going according to plan. The only hiccup came on New Year’s Eve, when the day passed without any news about the planned deployment of two booms that would extend the sunshield to its full size.

| “I’d be wiping my forehead if you could see me,” said Ochs. “Mid-boom deployment was huge. That was really a huge achievement for us.” |

Late in the day, NASA said the first of the two booms was now extended and the second was in progress. The delay, it said, was because of sensors that indicated a sunshield cover had not rolled up as expected. Other data, though, was consistent with the sunshield covers having been removed, giving engineers confidence that they could move ahead. The other boom completed its deployment less than two hours before East Coast calendars rolled over into 2022.

“Today is an example of why we continue to say that we don’t think our deployment schedule might change, but that we expect it to change,” said Keith Parrish, JWST observatory manager at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, in a statement Friday after the deployment of the first of the two mid-booms (emphasis in original.)

“I’d be wiping my forehead if you could see me,” Bill Ochs, JWST project manager at Goddard, told reporters in an audio-only teleconference Monday morning. “Mid-boom deployment was huge. That was really a huge achievement for us.”

But, as Parrish said, the deployment schedule has changed, as expected. The original schedule called for beginning the tensioning of the sunshield layers the day after the mid-boom deployments. But NASA announced Saturday that, because the mid-boom deployments went late into the evening Friday, they would take Saturday off. “We do not want to burn out our team along the way,” Ochs said.

The start of the tensioning process slipped to Sunday, then slipped again to Monday. In a Sunday blog post, NASA said engineers wanted to take time “optimizing Webb’s power systems while learning more about how the observatory behaves in space,” but provided few additional details.

In the Monday morning telecon—the first with reporters since that celebratory post-launch briefing—Ochs said controllers worked on two issues. One was a “preset max duty cycle” in the solar arrays that kept them from producing enough power to meet all spacecraft activities.

Engineers addressed that problem by tweaking the settings on each of five panels of the full array, said Amy Lo, vehicle engineering lead Northrop Grumman, so that “each panel of the array could be optimized to work at their best duty cycle possible.” That process was completed Sunday.

“We got the arrays to where they ought to be in order to provide the power that we need on Webb. We’re power-positive, the arrays look good,” she said.

The other issue, Ochs and Lo said, was with motors used to tension the sunshield. The temperatures were higher than expected, but still within margins. “We like to have a lot of operating margin for our motors—in fact, for anything that we do,” Lo said. “As we looked at the temperatures of the motors, they did not have as much margin as we would have preferred.”

The solution, she said, was to temporarily reorient the spacecraft so there was less sunlight shining on, and heating up, the motors. “They’re nice and cool. We’ve got a lot of margin now on our temperature.”

JWST will be fully deployed within a few weeks, although commissioning of the telescope and its instruments will take several more months. (credit: NASA GSFC/CIL/Adriana Manrique Gutierrez) |

Even as they spoke, controllers had started the tensioning process on the first of the five layers. Ochs said they will work layer by layer over two to three days to stretch the layers into the final shape, ensuring the proper separation between each layer so they can effectively cool the telescope and instruments.

| “The best thing for operations is boring, and that’s what we anticipate over the next three days, to be boring,” said Ochs. |

Completing the deployment of the sunshield won’t be the final step in getting JWST ready, but it will mean much of the most challenging work will be behind the team. “When we complete tensioning of all five layers,” Ochs said, “we will have retired somewhere between 70 to 75% of those 344 single-point failures that were discussed prior to the mission. That is huge.”

“I don’t expect any drama,” he added. “The best thing for operations is boring, and that’s what we anticipate over the next three days, to be boring. I think we’ll all breathe a sigh of relief once we get the final layer, layer 5, tensioning.”

In other words, as the tension in the sunshield increases, the tension among scientists and engineers will decrease. Assuming, of course, no drama in the process.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Monday, January 3, 2022

A Cosmic Blast

Cosmic Blast

A recent study on massive solar flares could reveal new information about the early days of the solar system, Cosmos Magazine reported.

Last year, astronomers began observing EK Draconis, a star located dozens of light-years from Earth, which makes it relatively close in distance.

EK Draconis is younger than the sun – about 100 million years old, compared to our star’s 4.6 billion years. The team explained that they monitored the young star to determine whether it was more prone to releasing massive bursts of energy and charged particles, known as a coronal mass ejection (CME).

To their astonishment, researchers saw that EK Draconis was capable of blasting a monster-sized CME that could travel at nearly one million miles per hour. They described EK Draconis’ superflare as 10 times larger than the most powerful ejection ever recorded from an older star, such as our sun.

Co-author Yuta Notsu noted that CMEs can be particularly dangerous if they hit Earth because they would completely fry all electrical systems, causing blackouts and disruptions.

He warned that a mass ejection as seen in EK Draconis “could, theoretically, also occur on our sun,” but added that our star’s advanced age makes an apocalyptic CME less likely.

Even so, Notsu and his colleagues suggested that the CME study could explain how the celestial events helped shape the early solar system and planets such as Earth and Mars.