|

Review: Not Yet Imagined

by Jeff Foust

Monday, January 17, 2022

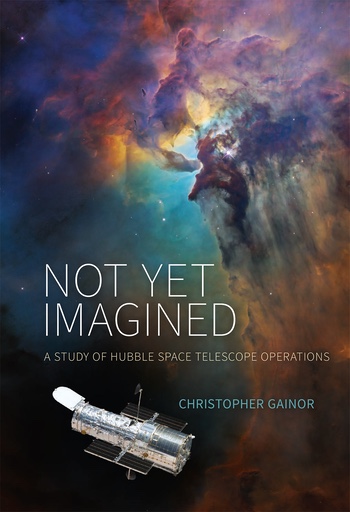

Not Yet Imagined: A Study of Hubble Space Telescope Operations

by Christopher Gainor

NASA, 2021

ebook, 452 pp., illus.

free

The James Webb Space Telescope is, in many respects, unlike any other astrophysics mission launched to date: a massive telescope that required an intricate series of deployments after launch last month to take its final shape, with months of commissioning of its mirrors and instruments still ahead, all to peer deeper into the universe than any previous observatory. Yet, it’s based on the legacy and the institutions of its predecessors, notably the Hubble Space Telescope.

That legacy is examined in Not Yet Imagined, a book from NASA’s history office about the operations of Hubble. Historian Christopher Gainor examines Hubble after its 1990 launch through nearly the present day, a three-decade span with both setbacks and major accomplishments scientifically and technically.

| Gainor estimates that the full cost of Hubble, including operations and the shuttle missions to launch and service it, is around $20 billion in present-day dollars. |

Gainor summarizes the long development of Hubble in an introductory chapter before turning his attention to its operations after launch, starting with the realization just a couple months later that the telescope’s primary mirror had been improperly shaped, a blow not just to astronomers but also to the agency’s reputation. That led to efforts to develop corrective optics installed on a December 1993 servicing mission that repaired the telescope as well as public perceptions of NASA.

Three more servicing missions followed through 2002, replacing instruments and making other improvements to Hubble. Planning was underway for a fifth servicing mission, and even consideration of a sixth, when the Columbia accident took place in 2003, grounding the shuttle fleet. NASA’s leadership decided a year later to abandon plans for that fifth servicing mission because of the risks involved, a move that generated professional, political, and public efforts to overturn it. After studies of a potential robotic servicing mission, a new NASA administrator, Mike Griffin, restored that shuttle servicing mission, which flew in 2009.

Besides the series of shuttle servicing missions, Gainor examines the more routine operations of the observatory, from the process of applying for telescope time to how the observations take place and the data placed into the hands of astronomers. He also examines the roles of institutions like NASA and the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), which handles the science operations of Hubble (and also JWST), play in Hubble. That extends to issues such as diversity in the field of astronomy: STScI hosted a conference on women in astronomy in the early 1990s that led to the “Baltimore Charter” of recommendations to improve the status of women in the field, yet the institute itself later had problems attracting and retaining female staff.

One question that the book takes on is the value of Hubble. Gainor estimates that the full cost of Hubble, including operations and the shuttle missions to launch and service it, is around $20 billion in present-day dollars. That is a lot of money, albeit spread out over several decades, but Hubble has become over that time the world’s most famous telescope. Data from the telescope has been used in more than 16,000 scientific papers as of 2019, he notes. It also helped build support not just for future space telescopes like JWST but also the International Space Station: the success of the 1993 servicing mission, with a series of complex spacewalks to repair the telescope, provided reassurances to NASA and the White House that the space station was feasible. Hubble and its images have become cultural touchstones, which could explain the outpouring of support when NASA said it would cancel the fifth servicing mission. Compare that to the ridicule it faced in the early 1990s: Gainor notes that, in the 1991 comedy The Naked Gun 2½, a picture of Hubble was on the wall of a bar along with notable disasters like the Titanic and the Hindenberg.

| Astronomers remain hopeful Hubble can keep operating through the middle of the decade and beyond. That is a longevity that, when the mission was originally designed with a 15-year life, could not be imagined. |

Some of the lessons from Hubble won’t be directly applicable to JWST. A key one is servicing: while Hubble’s life was extended, and its capabilities increased, with servicing, JWST is on its own at the Earth-Sun L-2 point, 1.5 million kilometers away. (There had been some discussion before the launch of a robotic refueling mission for JWST, but the precise Ariane 5 launch, saving fuel for stationkeeping that could double its life, may but the brakes on that.) But JWST will take advantage of the science and operational lessons of Hubble, and even some lessons from Hubble’s commissioning. In 1990, NASA officials agreed to release first images from Hubble as soon as possible, but JWST officials say they’ll hold off on showing those first images until the commissioning is complete months from now. One reason for doing so, a project scientist said at a briefing earlier this month, is that it will take a lot of work to align JWST’s mirrors; those first images “will be ugly.”

Hubble itself continues. The telescope remains in remarkably good condition despite being more than a dozen years since the final servicing mission. While it has encountered a number of technical problems in recent years, engineers have been able to restore full operations and astronomers remain hopeful Hubble can keep operating through the middle of the decade and beyond. That is a longevity that, when the mission was originally designed with a 15-year life, could not be imagined, much like its scientific and broader legacy.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

No comments:

Post a Comment