SXSW attendees line up to attend a screening of Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood in Austin, Texas, March 13. (credit: J. Foust) |

Reviews: Space films at SXSW

by Jeff Foust

Monday, March 21, 2022

Space has had a growing presence in recent years at South by Southwest (SXSW), the annual film, music, and technology festival in Austin, Texas. That presence has largely been limited to the technology conference sessions, with panels on topics from space commercialization to the search for life beyond Earth. This year’s SXSW earlier this month—the first in-person festival since 2019 because of the pandemic—included a two-day “Space Rush Summit” with two tracks of panel discussions, as well as some other scattered space-related events.

This year’s SXSW saw space make its way into the film festival as well. Several films screened at SXSW had links to space, from documentaries to movies that took some inspiration from spaceflight.

|

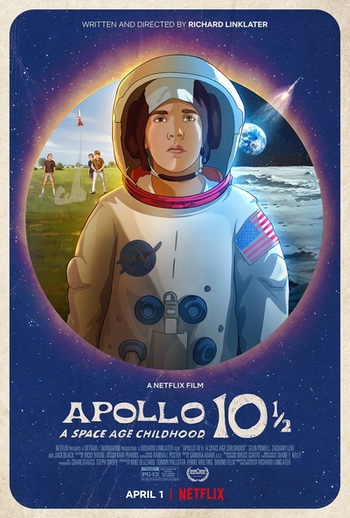

The most prominent of those movies was Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood, directed by Richard Linklater (Before Sunrise, Boyhood, Dazed and Confused, among others.) The movie is a semi-autobiographical account of Linklater’s own childhood in Houston, not far from NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center (now Johnson Space Center) in the summer of 1969. The film uses rotoscope animation, like some of Linklater’s previous movies, making it appear like some hybrid of reality and imagination.

The central character is Stan, a boy in an elementary school not far from the NASA center. The title comes from Stan’s fantasy weaved into the film that NASA asks him to train for a secret mission to the Moon using a lunar lander accidentally built too small. He trains for the mission and goes to the Moon, in this fantasy, allowing Apollo 11 to go ahead.

The movie is really a nostalgic trip back to the late 1960s in a place where everything seemed new and the future was everywhere, from space-themed ads for car dealers to an early introduction of touch-tone phones. Linklater vividly recreates growing up in those Houston suburbs in that era, where the trauma of those years—assassinations, riots, Vietnam—seemed like a world away.

| “NASA is, by far, my favorite government agency,” Linklater said. |

Linklater and others working on the movie paid close attention to detail, such as looking up TV and movie listings from the time so that when someone changed the channel from launch coverage, it accurately showed what was on another channel.

The filmmakers also worked closely with NASA, turning actual footage of the Apollo missions into animation. “NASA is, by far, my favorite government agency,” Linklater said on stage after a screening of the movie at SXSW. He revealed that the movie was recently screened on the International Space Station and that he and others involved with the film, including Jack Black, who narrates the movie as an older Stan, talked with ISS astronauts Raja Chari and Thomas Marshburn, the latter old enough, like Linklater, to recall being a kid in that era.

Apollo 10½ isn’t about space, but rather how the space program of the late ’60s was a central part of a childhood growing up in Houston at a time, especially for a child, where the future seemed limitless. Apollo 10½ will be available on Netflix in April.

|

While Apollo 10½ mixed a documentarian’s rigor with fantasy and animation, It’s Quieter in the Twilight is more of a conventional documentary. The film, directed by Billy Miossi, is about NASA’s Voyager spacecraft to the outer solar system, particularly now in the twilight of the mission and people still working on it.

In its heyday, when the two spacecraft were being bult and then operated through their flybys of the outer planets, more than 1,000 people worked on Voyager. By the time the documentary picks up the mission, in 2019, the staff is down to a dozen, most of whom have been involved with Voyager for decades. A mission that once attracted the world’s media to JPL now wasn’t even run from JPL itself: the staff worked from a nondescript office building a few kilometers from the main JPL campus, next to a McDonalds. “Being here… you’re forgotten here,” said Suzanne Dodd, the Voyager project manager.

Both spacecraft continue to operate more than 40 years after launch, having crossed the heliopause into interstellar space. They are, though, “senior citizens,” as Dodd puts it, aging in different ways. Voyager 2, for example, has less power and is colder, and is in danger of having its hydrazine fuel freeze. It can also only communicate with a single Deep Space Network antenna in Australia, one that, as the documentary beings in 2019, is preparing to go offline for upgrades.

| The two Voyager spacecraft are “senior citizens,” as Dodd puts it, aging in different ways. |

The film follows the small Voyager team as they work to prepare Voyager 2 to operate on its own for months without contact from Earth. Threaded through that is a history of Voyager as well as profiles of some of the people working on the mission now. They come from a wide range of backgrounds, some having emigrated from Colombia and Korea, many having spent much of their careers working on Voyager. Like the spacecraft themselves, they are becoming senior citizens but unwilling to retire while the spacecraft keep working.

The film’s dramatic pacing comes from that effort to get Voyager 2 ready before the DSN antenna is taken offline, overcoming technical glitches and external challenges that include the onset of the pandemic in early 2020 just as Voyager 2’s silence begins. And while they overcome those problems, they know the end is inevitable: the RTGs that power the two spacecraft are decaying, their power levels dropping in a predictable fashion that shows that, by the end of the decade, they will no longer have enough power to run their instruments or communicate with Earth. But the mission continues, quietly, in its twilight years.

|

The summary of the new movie Linoleum is simple: “When the host of a failing children's science show tries to fulfill his childhood dream of becoming an astronaut by building a rocket ship in his garage, a series of bizarre events occur that cause him to question his own reality.” With Jim Gaffigan playing that lead character, one might expect it to be some kind of comedic version of The Astronaut Farmer (see “Review: The Astronaut Farmer”, The Space Review, February 26, 2007).

It’s not. Gaffigan plays Cameron, a poor man’s version of Bill Nye on a local TV station in what appears to be the 1980s—there are VHS tapes but no Internet, for example. He’s about to lose his show, though, while his wife (Rhea Seehorn), working at an air and space museum, plans to file for divorce. Then a satellite crashes in his backyard, triggering that desire to build a rocket.

Expect the movie isn’t about building a spaceship, at least not literally. (NASA did not appear to cooperate in the movie, as evidenced by the ersatz NASA logo on a spacesuit Gaffigan has.) Instead, the crashing spaceship and desire to build a rocket serve as vehicles for a broader examination of life and aging. It’s an entertaining movie, but one that takes you to different places that what the synopsis might lead you to believe.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

No comments:

Post a Comment