A second chance at the Moon

by Jeff Foust

Monday, April 18, 2022

Companies rarely get second chances at competitions they lose. Unless a contract is overturned by a protest or other legal action, bidders who lose out on government contracts have to lick their wounds and try again on a future program.

| “Today’s announcement is what I said to Congress,” Nelson said. “I promised competition, so here it is.” |

But for the companies that lost out in the Human Landing System (HLS) competition to SpaceX last year, an effort that prompted both unsuccessful protests with the Government Accountability Office and a lawsuit rejected in federal court, there will be a second chance to offer landers capable of taking astronauts to and from the lunar surface. That second chance, though, doesn’t mean a repeat of the same teams offering the same landers.

On March 23, in an announcement made on short notice days before the release of the agency’s fiscal year 2023 budget proposal, NASA announced a new initiative, called Sustaining Lunar Development. The program will support creation of a second lander alongside SpaceX’s Starship selected for the HLS program’s single Option A award last year (see “All in on Starship”, The Space Review, April 19, 2021).

NASA officials said Sustaining Lunar Development was fulfilling a pledge to have competition in the overall HLS effort, something originally envisioned by selecting more than one company for an Option A award. Last April, NASA officials explained that they had the funding for only a single award, which went to SpaceX for $2.9 billion, an amount that was far less than competing bids from Blue Origin and Dynetics.

“Today’s announcement is what I said to Congress,” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said in a call with reporters about the announcement, referring to statements to members who pressed NASA last year to select a second lunar lander provider. “I promised competition, so here it is.”

It is, though, a different kind of competition than was originally envisioned under HLS. The winning company will move directly into work on a more advanced lunar lander designed to support NASA’s “sustainable” phase of lunar exploration later in the decade. That moves from initial “sortie” missions, carrying two people who spend a week on the surface, to “excursion” missions lasting up to a month with four people.

“Beyond Artemis 3 we want to increase the healthy competition and advance our lunar capabilities to support more science, more exploration, and an emerging lunar marketplace,” Jim Free, NASA associate administrator for exploration systems development, said at the briefing.

Agency leaders were quick to explain that the decision to proceed with Sustaining Lunar Development did not reflect any buyer’s remorse or other dissatisfaction with SpaceX. The GAO protest and lawsuit delayed the start of SpaceX’s HLS work by more than half a year, but NASA managers said they were pleased at SpaceX’s work since then.

“I’ve spoken recently with [SpaceX president] Gwynne Shotwell, and our teams are making good progress on the demonstration HLS award,” Nelson said, which includes the Artemis 3 landing.

| “Many folks have told us, ‘We’ve learned a lot and we think our bids can be better this time,’” Free said. |

SpaceX will not be eligible to compete for the Sustaining Lunar Development award in order to preserve competition (although, agency procurement officials later said, bidders could have SpaceX as a subcontractor if, for example, they wanted to launch their landers on SpaceX vehicles.) Instead, NASA will exercise an option in SpaceX’s HLS award, called Option B, to bring its Starship lander up to the specifications for those later sustainable missions.

The announcement left unanswered many details about the new program, not the least of which was its budget. Blue Origin’s and Dynetics’ bids for the original HLS competition were significantly higher than SpaceX’s winning bid, and that was for the original Option A capability and not the greater demands of the new competition.

Agency leaders declined at the time to discuss budget details, noting the fiscal year 2023 budget proposal would soon be released. “Many folks have told us, ‘We’ve learned a lot and we think our bids can be better this time,’” Free said.

That budget proposal, though, didn’t answer many questions about the budget for lunar lander development. After NASA got its full request of $1.195 billion for HLS in a fiscal year 2022 omnibus spending bill approved in mid-March, the 2023 proposal asked for $1.486 billion for HLS. It did not, though, spell out how much of that would go to Sustaining Lunar Development versus the existing Option A and planned Option B awards to SpaceX.

“I can’t break that out for you,” Free said when asked in a media teleconference about the budget proposal March 28 for how the HLS funding would be allocated. “We’re not going to break it out because then we give the number that is available for the procurement, and that changes how the procurement is run.”

However, more than two years ago, when NASA released its fiscal year 2021 budget proposal, it included estimates for funding of the HLS program for 2021 through 2025 while NASA was still considering proposals for initial “base period” contracts, and long before requesting Option A proposals.

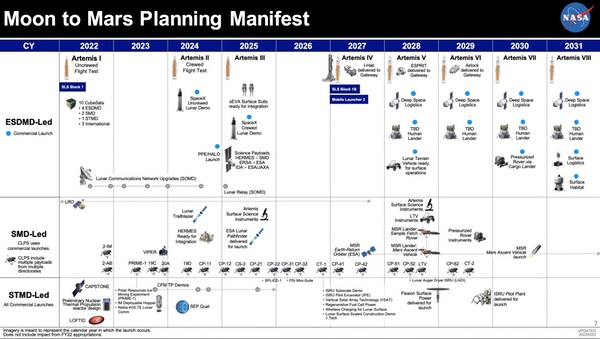

There will also not be a rush to develop that second lander. NASA used the budget rollout to release an updated timetable for the Artemis program, with the uncrewed Artemis 1 launch this year and Artemis 2 in 2024. The Artemis 3 mission, with the SpaceX landing on the Moon, was still set for 2025. However, Artemis 4 would not follow until 2027, and that would be a mission only to the lunar Gateway, delivering a habitation module to be built by Europe and Japan. The next landing mission, Artemis 5, would be in 2028, and be the first opportunity for that second lunar lander to fly.

A chart from a NASA budget presentation showing that, after Artemis 3 in 2025, the next Artemis crewed lunar landing would not be until Artemis 5 in 2028. (larger version) |

Despite uncertainties about cost and schedule, companies that bid on the original HLS competition are lining up to express their interest in Sustaining Lunar Development. That included Blue Origin, which protested the SpaceX HLS award to the GAO and later filed suit, unsuccessfully, in the Court of Federal Claims. “Blue Origin is thrilled that NASA is creating competition by procuring a second human lunar landing system,” the company said in a statement after NASA’s initial announcement about Sustaining Lunar Development. “Blue Origin is ready to compete and remains deeply committed to the success of Artemis.”

The same was true for Dynetics, which also filed a protest with the GAO but, unlike Blue Origin, didn’t go to court when the GAO rejected its protest. “As a current performer on NASA’s Appendix N contract, we have made great progress in our lander design and risk reduction,” a reference to risk reduction awards NASA made last September to several companies for future lunar landers that is part of its Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP) program.

However, those statements don’t mean that those companies will bid, or bid with the same teammates as the original HLS competition. Blue Origin’s bid was part of its “National Team” that included Draper, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman. Blue Origin, Lockheed, and Northrop all received NextSTEP Appendix N awards, but even then Lockheed and Northrop officials said they were leaving the door open to alternatives to the National Team.

At a March 30 webinar, Northrop officials said the company had yet to decide how they would participate in Sustaining Lunar Development. “We’ve done our own studies on the Human Landing System and we’ve worked with the National Team and Blue Origin,” said Rick Mastracchio, director of business development for human exploration and operations at Northrop Grumman. “Right now we’re in the decision-making process on that, and hopefully that will be a decision that comes out in the next few weeks.”

| “That changes the discussion of what capability you want to bring to the table,” Lightfoot said of the new competition. “For us, anything we do we want to be extensible to Mars. That’s important to us.” |

Lockheed Martin is also considering its options. The announcement of the program and the release, a week later, of the draft request for proposals, came just before the annual Space Symposium conference in Colorado Springs, Colorado, a major space industry meeting. Some companies, like Lockheed, used the event to set up meetings with prospective partners for the competition.

“Space Symposium was actually a perfect opportunity for us because anybody we want to talk to, we can get together like that,” said Robert Lightfoot, the executive vice president for Lockheed Martin Space, during an interview at the conference.

Lightfoot, a former NASA associate administrator and, for more than a year, acting administrator, said the company planned to participate in the Sustaining Lunar Development competition but hadn’t decided on a specific teaming strategy. “We’re going to be in the game somewhere.”

He emphasized that the company didn’t see the new competition as a repeat of the original HLS competition, which at the time was driven by a goal of returning humans to the surface of the Moon by 2024. “That changes the discussion of what capability you want to bring to the table,” he said. “For us, anything we do we want to be extensible to Mars. That’s important to us.”

While the National Team had four major companies, the Dynetics bid featured an even larger group of companies and organizations. One of the major ones was Sierra Nevada Corporation’s space unit, which has since been spun off in a separate company called Sierra Space.

In an interview, Tom Vice, CEO of Sierra Space, suggested that if the company participates in the Sustaining Lunar Development competition, it would be with Blue Origin. The two companies are currently working closely together on Orbital Reef, the commercial space station concept that was one of three that won NASA funding in December for initial studies.

“We have a very unique, strong relationship with Blue Origin,” he said. “We would probably think about how do we partner with them.” He added that he didn’t see the company leading its own team to bid on the lander, focusing its efforts instead on development of its Dream Chaser vehicle and its support for Orbital Reef.

Those decisions will need to come soon. NASA expects to release a final version of the lander RFP in the summer, with proposals due 60 days later. That would allow NASA to make a contract award by January 2023.

“This budget is a really good start to the competition,” Bob Cabana, NASA associate administrator, said in a call about the proposed 2023 budget. “This gets us on the right path.”

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

No comments:

Post a Comment