Is China’s rise in space over? Indexing space power for the next space age

by Daniel Duchaine

Monday, July 31, 2023

We will soon enter an age where space is not merely a domain to support Earth but another region, with regional great power competition. As space becomes a true region, international relations tools will become increasingly more enlightening. In this paper, I seek to introduce a way to track “Space Power” by creating an index showing which countries are great powers in space, which countries hold the greatest share of this power in space, and tracking this over time and into the future. Understanding these dynamics is vital for understanding the most likely sources and periods of conflict and cooperation.

The Space Power system

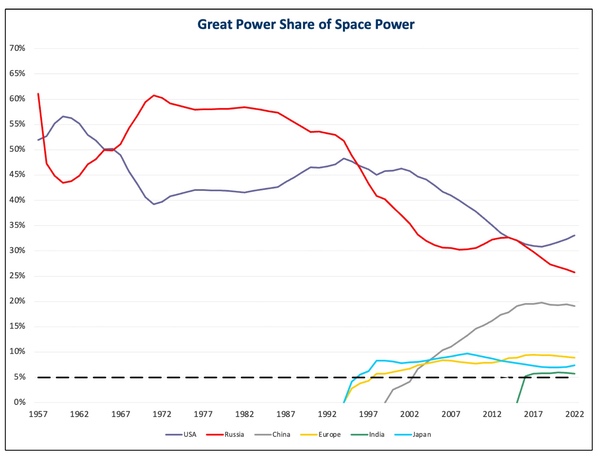

While space is not yet a true region of great power competition, it is emerging as one, and we should start considering the implications now. Sometimes scholars define a great power is a state with more than 5% of global power. It is arbitrary, but I would argue mostly accurate. I will consider great powers in space a state with more than 5% of the total Space Power. Space Power is an index based on cumulative orbital launches, deep space orbital launches, space scientific achievements, and space military capabilities. While I considered every state with a space program, only those that cracked 5% of total space power at some point in their history were included in the system.

| While space is not yet a true region of great power competition, it is emerging as one, and we should start considering the implications now. |

“The Great Power Share of Space Power” graph below shows the bipolar system of the US and the USSR throughout the Cold War; it shows the collapse of the USSR; and it shows how Japan, Europe, and later China and India emerged as great space powers. Importantly, it shows how the rise of one state can eat into the total share of power of the others. Japan’s and Europe’s entrance into the system precipitated Russian decline, and China’s rise coincided with US decline. Recently, India’s entrance and the US’s resurgence coincide with the end of China’s rise in space.

|

The Space Power Index

Cumulative orbital launches

I chose cumulative orbital launches as an input for a number of reasons. First, it shows that a state has the technological capacity to design, build, and deploy space technology. Second, it shows that the state has a high industrial capability, required for launching large numbers of satellites. Third, it is a reliable and easy to find datasets that are consistent for all states. Some drawbacks to cumulative orbital launches are that it overvalues constellations, which includes dozens of satellites in one launch, and it does not account for payload size nor complexity.

Deep space orbital launches

Deep space capabilities show a state has sophisticated technological and scientific capabilities, and it will be vital for future space projects to take advantage of asteroid mining or colonize other worlds. Since this is such a forward looking input, I decided to only count it in the index after 1990, the start of the second space age.

Scientific achievements

This input is a binary for 10 different achievements: satellite launch, Moon hard landing, Moon soft landing, Venus landing, Mars hard landing, Mars soft landing, asteroid/comet landing, human spaceflight, space station operation, and human lunar landing. When a state accomplished one of these achievements, it gained one unit of the input. Scientific achievements show that the state is able to overcome significant scientific and technological challenges. However, being a binary means that it oversimplifies the scientific process and does not easily account for regression. Furthermore, it is a small dataset.

Military capabilities

Similar to scientific achievement, this index is based on whether a state is thought to have military capabilities in space including: LEO co-orbital, MEO/GEO co-orbital, LEO direct ascent, directed energy, electronic warfare, or space situation awareness capabilities. A state got 0.5 units for some capabilities, and 1 unit for significant capabilities, as defined by the Secure World Foundation Counter-space Capabilities Report. However, military technology like this is highly classified, and the extent and the exact year that states develop these capabilities is foggy at best.

| Plateaus in relative power after a rise are not immediately followed by another rise in power. |

This index may seem subjective, and it is. Great power status is inherently subjective. It depends on whether the rest of the international systems considers your country as a great power. India probably wasn’t objectively a more powerful country the day before it launched a direct ascent ASAT, but doing so got the attention of the rest of the system. So the goal for this index is to track things that would make a country seem powerful. You can check my data as a Microsoft Excel sheet here.

Case studies

The newest great space power

India made an explosive entrance into the great power space system in 2019, as a result of two groundbreaking developments in its space program. India demonstrated its direct ascent anti- satellite (ASAT) capability, a feat previously achieved by only a handful of countries; and unveiled its space electronic warfare capability. The rise of India into the system seems to be most damaging to China, whose share of power began to plateau as a result.

US resurgence

Since the turn of the millennium, the United States experienced a noticeable decline in its share of global space power, a trend that can largely be attributed to China’s rise in space. However, there has been a resurgence in recent years, fueled by a significant uptick in American space launches. This growth of American space power, largely being driven by private companies, signals a continuation of the US role as the hegemonic space power.

The end of China’s rise?

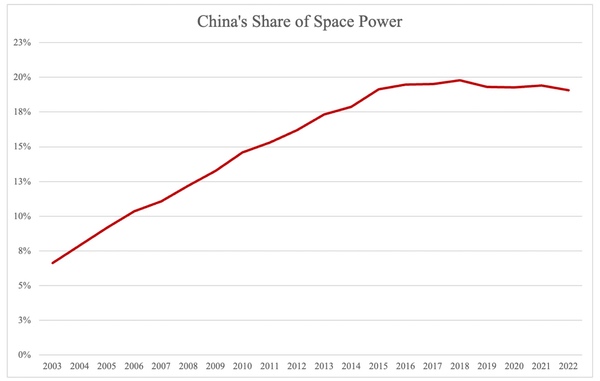

China's emergence as a great space power in 2003 marked a turning point in the global space race, with the nation rapidly rising through the early to mid-2010s. China tested a direct ascent ASAT, landed a rover on the Moon, and passed Japan and Europe in objects launched. Ambitious government initiatives, significant investments in technology, and a rapidly growing Chinese economy and industrial base fueled this rise.

|

The landscape began to shift in 2018. Though China continues to increase its space power, the resurgence of the US in space activities and the entrance of India exerted a downward pressure on China’s relative share of space power. This led to a noticeable plateau in China’s once meteoric rise. Plateaus in relative power after a rise are not immediately followed by another rise in power. Japan and Europe’s rise and plateau continued for 20 years and shows no end in sight. The USSR’s rise, peak, and then rapid decline in the 1970s and the US’s rise, peak, and decline in the early 2000s could be next for China.

What does this mean?

Conflict

Historically, conflict between the great powers is more likely when there is a fundamental shift in share of relative power. The most famous example of this is World War I. The Congress system, though flawed in many ways, maintained peace for almost 100 years. This was possible because the share of relative power in the system was stable. It was the rise of Germany, and then the rise of Russia, which caused Germany to plateau, that ultimately ended the century of peace. (It is difficult to do this theory justice in one paragraph. See Professor Charles Doran’s book Systems in Crisis for a better explanation of Power Cycle Theory.) The US recently shifted from decline to rise, and Chinese share of power shifted from rise to plateau. Could this be the end of the long peace in space?

Diplomacy

States can avoid war during shifts in relative power with skillful diplomacy. The USSR collapsed in the 1990s, but the US and the USSR were able to avoid war by carefully managing the relationship. Though periods of relative power shift correlate with war and conflict, with skillful diplomacy, war can be avoided. Therefore, it is vital that policymakers realize the risks associated with these periods and promote diplomacy and cooperation whenever possible. Humanity’s future in space is too valuable to risk.

References

Bingen, Kari A., Kaitlyn Johnson, and Makena Young. Space Threat Assessment 2023. CSIS Aerospace Security Project, 2023.

“Countries with Space Programs.” World Population Review. 2023.

Doran, Charles. Systems in Crisis. Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Goswami, Namrata, and Peter A. Garretson. Scramble for the Skies: The Great Power Competition to Control the Resources of Outer Space. Lexington Books, 2020.

Harrison, Todd, Cooper, Zack, Johnson, Kaitlyn Roberts, Thomas G. “Escalation and Deterrence in the Second Space Age.” CSIS Aerospace Security Project, 2017.

McDowell, Jonathan C. "General Catalog of Artificial Space Objects." Release 1.2.3, 2021. Updated July 11, 2023.

“Online Index of Objects Launched into Outer Space.” UNOOSA.

“UCS Satellite Database.” Union of Concerned Scientists, 1 Jan. 2023.

Weeden, Brian and Samson, Victoria. Global Counter Space Capabilities. 2023.

You can find the Space Power Index data as an Excel Sheet here.

No comments:

Post a Comment