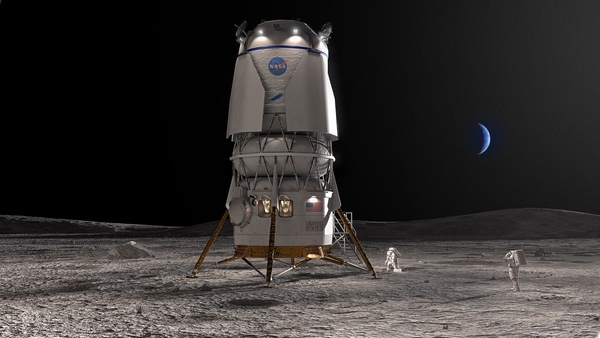

Blue Origin won a $3.4 billion NASA award to develop this new version of its Blue Moon lunar lander to carry astronauts to the lunar surface, starting on Artemis 5 at the end of the decade. (credit: Blue Origin) |

A lunar lander makeover

by Jeff Foust

Monday, May 22, 2023

Two years ago, NASA surprised many in the space industry when it selected SpaceX, and only SpaceX, for its Human Landing System (HLS) program, awarding the company $2.9 billion to develop a lunar lander version of its Starship vehicle to carry astronauts to the lunar surface on Artemis 3 (see “All in on Starship”, The Space Review, April 19, 2021). That prompted the two losing bidders, teams led by Blue Origin and Dynetics, to file a protest with the Government Accountability Office (GAO). When the GAO rejected the protest three months later, Blue Origin then went to federal court, only to have the Court of Federal Claims rule against the company that November (see “Resetting Artemis”, The Space Review, November 15, 2021.)

| “It means that you have reliability, you have backups,” Nelson said of two landers. “It benefits NASA, it benefits the American people.” |

Both Blue Origin and Dynetics would get second chances, though, when NASA announced in March 2022 that it would hold a second competition (see “A second chance at the Moon”, The Space Review, April 18, 2022). NASA argued all along that it planned to select two landers, but funding constraints prevented it from doing so. Those funding constraints had not been resolved, but the agency—spurred on by some members of Congress—pressed ahead with a new competition called Sustaining Lunar Development to pick a second lander that would support larger crews and longer stays on the lunar surface needed for later Artemis missions. (SpaceX would not be eligible to compete, but NASA exercised an option on its existing award to SpaceX worth more than $1.1 billion to upgrade Starship for to meet those requirements.)

After a December deadline for proposals, both Blue Origin and Dynetics, and no one else, announced they had put in bids. Neither company disclosed many details about their revised proposal, with Dynetics releasing an illustration of its lander that looked much like its original design. Perhaps the biggest change was that Northrop Grumman, who has been part of Blue Origin’s “National Team” in the original competition, instead joined the Dynetics bid. Blue Origin said little about its team other than to emphasize it included suppliers in 48 states (sorry, Nebraska and North Dakota.)

NASA said at the time it expected to make a selection by June, so it was a little surprising when the agency said last week it would announce the winner on Friday. At the event at NASA Headquarters, administrator Bill Nelson reiterated his desire to have two landers. “It means that you have reliability, you have backups,” he said. “It benefits NASA, it benefits the American people.”

After that brief windup, Nelson made the announcement: Blue Origin would get the Sustaining Lunar Development award to build that second lander, a deal agency officials said was worth $3.4 billion.

Two things became clear during the announcement and the release hours later of the source selection statement document, where the agency outlined how it decided to pick Blue Origin. One was that the Blue Moon lander was very different from what the company had proposed in the original HLS competition or earlier lander designs under that name. The HLS bid involved a modular approach, with a transfer vehicle from Northrop that would take the lander from the Gateway down to low lunar orbit, a descent stage from Blue Origin, and an ascent stage, which included the crew cabin, from Lockheed Martin.

In the original HLS competition, a “National Team” led by Blue Origin proposed a lunar lander significantly different from the version NASA selected this month. (credit: Blue Origin) |

The new Blue Moon lander is a single-stage design Blue Origin would develop that could land, take off, and be refueled and reused. “The lander is optimized for our seven-meter fairing on New Glenn,” said John Couluris, program manager for HLS at Blue Origin, at the briefing. “We specifically optimize height and mass for New Glenn.”

The lander is 16 meters tall and weighs 16 metric tons dry, or without any propellant on board. When loaded with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants, its mass increases to more than 45 metric tons, he said. A large liquid hydrogen tank dominates the upper part of the vehicle, with a liquid oxygen tank below it. The crew cabin is near the bottom, allowing astronauts relatively easy access to the surface.

That design, he said, enables landing anywhere on the lunar surface, day or night. It also requires extensive development of technologies to keep both the liquid oxygen and, especially, the liquid hydrogen from boiling off while on the lunar surface or in orbit awaiting the arrival of astronauts.

“We’ve been funding our zero-boiloff effort for some time at Blue Origin,” Couluris said. “We want to make hydrogen a storable propellant because we believe that not only does that open permanency on the Moon, but also enables the rest of the solar system via other technologies, such as nuclear thermal propulsion. If you can make hydrogen storable, then you can do a number of things.”

He said those efforts have included NASA “Tipping Point” technology development awards to support work on cryogenic propellant storage and transfer. He didn’t go into details about those technologies other than to say they include a cryocooler that operates at temperatures of 20 kelvins.

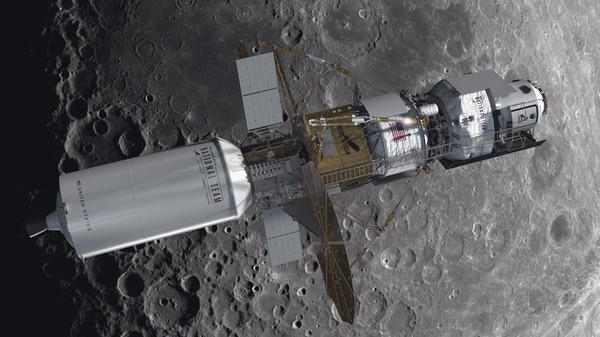

The lander will be supported by a “cislunar transporter” spacecraft that Lockheed Martin will develop, carrying propellant from Earth orbit to the lander in the near-rectilinear halo orbit around the Moon. (The lander will need to be refueled in lunar orbit before attempting a landing.) Draper will provide guidance, navigation, and control technologies as well as training and simulation. Boeing will provide a docking system for the lander. Astrobotic and Honeybee Robotics will support cargo accommodation and offloading systems. Couluris noted Blue Origin is planning a cargo version of the lander that could place 20 metric tons of cargo on the surface and return to orbit, or deliver 30 metric tons on a one-way trip.

There was also a big difference in the price of the lander. The $3.4 billion Blue Origin proposed for this lander is far less than the nearly $6 billion it bid on the original HLS competition for a lander less capable than this one. Couluris said the company will contribute “well north” of $3.4 billion of its own money for Blue Moon’s development, eying both future NASA missions and unspecified commercial opportunities for the lander.

| “We want to make hydrogen a storable propellant because we believe that not only does that open permanency on the Moon, but also enables the rest of the solar system via other technologies,” said Couluris. “If you can make hydrogen storable, then you can do a number of things.” |

The second thing that was clear from the selection was that it was not a close competition between Blue Origin and Dynetics. “Blue Origin’s proposal is the most advantageous to the Agency across all evaluation factors, and it aligns with the objectives of the solicitation,” Jim Free, NASA associate administrator for exploration systems development, wrote in the source selection statement.

The statement identified several “significant strengths” of Blue Origin’s proposal. One was an aggressive schedule of test flights that could begin as soon as 2024. Those “pathfinder lander missions” would mature systems with low technology readiness levels, or TRLs, planned for the crewed Blue Moon lander while still early in its development.

“I find this aspect of the proposal to be compelling — it is a forward-thinking solution to mature key low-TRL technologies allowing for incorporation for any changes into the final design,” Free wrote, adding that Blue Origin, and not NASA, would fund those pathfinder missions.

Couluris mentioned at the briefing two “Mark 1” landers that will demonstrate technologies for future landers, like avionics and the BE-7 engine. Those are separate from the crewed version of Blue Moon, which will carry out an uncrewed landing and return to lunar orbit about a year before the first crewed flight as part of Artemis 5.

The Dynetics proposal, by contract, did not have any significant strengths, being credited for only offering excess capabilities, like Blue Origin, and for a business approach that envisioned other customers. It was, though, cited for significant weaknesses regarding whether the lander it proposed could meet all of NASA’s requirements and plans to mature eight major technologies on a uncrewed test flight just nine months before the planned crewed mission.

NASA did not disclose the value of Dynetics’ bid other than to say its price was “significantly higher” than Blue Origin’s proposal.

In a statement, Dynetics showed no signs it would protest the bid, possibly because of those significant technical and price disparities. “The Artemis missions require multiple partners to achieve success, and our Leidos-Dynetics team is committed to continuing to assist on these critical missions,” Dynetics (owned by Leidos) stated. It mentioned its work on other parts of Artemis and plans to bid on an upcoming NASA competition to develop a lunar rover called the Lunar Terrain Vehicle.

“Leidos will remain focused on developing advanced technologies and innovations to enable safe and sustainable exploration and discovery to the Moon and beyond,” the company stated.

Former astronaut Sen. Mark Kelly (D-AZ) speaks at a press conference last Thursday attended by the Artemis 2 crew and the heads of NASA and the Canadian Space Agency. (credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls) |

Technical and fiscal uncertainties

Other than the briefing and the source selection statement, neither NASA nor Blue Origin released many details about the new Blue Moon lander. Blue Origin’s own statement about the award was remarkably short, focusing primarily on its efforts to store liquid hydrogen.

The only illustration Blue Origin released of the lander was it sitting on the surface. Notably absent from the announcement were any details or descriptions of the cislunar transporter, including how many flights will be required to fuel Blue Moon for a lander mission. (Blue Origin had once criticized SpaceX’s Starship lunar lander approach, which requires several launches to fuel the lander in Earth orbit, as “immensely complex and high risk.”)

| “We need more public definition of schedules and issues and risks involved in lander development,” Hale said. “If we can’t land people on the Moon, we’re not going to get to Mars.” |

Transparency, though, has been an issue for the HLS program since NASA finally started work with SpaceX on its award in late 2021. Other than the spectacle of the inaugural Starship/Super Heavy launch last month, there have been few public updates on the progress SpaceX is making on developing the lander version of Starship.

Nelson, at the Blue Origin announcement, said all is well with that original HLS award. “They likewise have put a lot of skin in the game,” he said of SpaceX’s undisclosed contributions to Starship lander development. “That mission for the first lander is proceeding on schedule.”

That schedule currently projects Artemis 3 launching in December 2025. That means that, in two and a half years, SpaceX not only has to get Starship flying on a regular basis, but also demonstrate in-space cryogenic propellant transfer technology, and do all of that for an uncrewed demonstration landing about a year before Artemis 3. A tall order, to say the least.

At a May 15 meeting of the human exploration and operations committee of the NASA Advisory Council, Wayne Hale, lamented the lack of details. “We need more public definition of schedules and issues and risks involved in lander development,” he said. “It’s key to everything. If we can’t land people on the Moon, we’re not going to get to Mars.”

Free agreed at the meeting about the need for more progress on lander development, including launches and cryogenic propellant transfer. “There’s a lot that has to happen,” he said.

There are also budget concerns. NASA is projecting significant spending increases over the next five years on the HLS program, from nearly $1.9 billion in the agency’s fiscal year 2024 budget request to $2.75 billion in 2027 before declining slightly to $2.5 billion in 2028, the last year of the “outyear” budget projections included in the request. That and increased spending on advanced lunar systems account for the bulk of overall spending increases projected for the overall exploration budget, with mainstays like Orion and the Space Launch System remaining flat or declining over the next five years.

However, budget debates ranging from current negotiations about raising the debt ceiling that could include potential spending cuts to uncertainty about when, or if, Congress will pass a 2024 spending bill versus a full-year continuing resolution, raise doubts about how much funding will be available for HLS and other agency priorities.

Free, at the advisory committee meeting, acknowledged that those projections in the budget might not be sufficient. “I don’t think we’ll ever get all the dollars we think we need, but our job is to implement what the president would like to put forward and then whatever Congress eventually appropriates for it,” he said, noting there are inevitable differences between what NASA submits to the White House’s Office of Management and Budget and what eventually is released as the administration’s budget proposal.

“A lot of the program managers are here in the room,” he added, “and I’m sure they’d tell you they need more than this to execute.”

With that combined uncertainty of whether NASA’s proposed budgets are sufficient and whether Congress will even provide that much more money, the agency is on the offensive on Capitol Hill. Last week, as part of a visit to Washington, the four astronauts assigned to Artemis 2 spent time meeting with members of Congress.

The astronauts said they got a warm reception from the members they met with. “Folks are cheering us on and telling us how they’re going to support us and they’re going to make sure that we can keep doing the things that we’re doing,” said Victor Glover, pilot of Artemis 2, during a press conference outside the Capitol last Thursday. “They know how important the decisions and the debates that are happening right now are to the future sustainability of that vision and execution of that vision.”

| “I do get a lot of questions here about space. They’re usually really good questions from my colleagues,” Kelly said. “Sometimes they ask why the space shuttle isn’t landing on the Moon anymore.” |

Nelson was also at the press conference, and again warned of the effects of budget cuts on the agency. “The kinds of cuts that you have seen talked about would be devastating to NASA, to our programs and, indeed, this… crew that is taking us back to the Moon after half a century,” he warned.

Current astronauts come and go, but one former astronaut is there full time: Sen. Mark Kelly (D-AZ). He doesn’t serve either on the Senate Appropriations Committee, which funds NASA, or the Senate Commerce Committee, which authorizes NASA programs, but he said at the press conference outside the Capitol he regularly talks with fellow members of Congress on space issues.

“I do get a lot of questions here about space. They’re usually really good questions from my colleagues,” he said. “Sometimes they ask why the space shuttle isn’t landing on the Moon anymore.”

“My experience is they’ve been incredibly supportive,” he said, adding that support spans the political spectrum. “NASA is the Dolly Parton of government agencies. Everybody loves Dolly Parton.” The question will be whether everyone loves NASA enough to ensure it gets funding to keep two lunar lander projects, among many other priorities, on schedule.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

No comments:

Post a Comment