The Moon is harsh on missteps

by Jeff Foust

Monday, May 1, 2023

The scene was both familiar and disappointing. A crowd had gathered in the middle of the night at a Tokyo museum to watch HAKUTO-R M1, the first spacecraft by Japanese company ispace, attempt a soft landing on the Moon. The lander, launched in December, had entered orbit around the Moon in March after following a low-energy trajectory, and was now making its descent towards Atlas Crater.

| “At this moment, we have not been able to confirm a successful landing on the lunar surface,” said Hakamada. “So, we have to assume that we could not complete the landing on the lunar surface.” |

Much of the initial phases of the planned hour-long descent took place out of contact, with the spacecraft on the opposite side of the Moon. When it emerged back into view, ispace reported restoring contact with the lander, but provided few updates beyond an animated display of the lander’s descent that, to the confusion of many, mixed actual and simulated data.

However, ispace indicated all was going well with the lander as it made its final approach for a landing scheduled for 12:40 pm EDT Tuesday, or 1:40am Wednesday in Tokyo. The webcast showed the company’s top executives watching in anticipation as the animation depicted the lander in its final phases of descent until it touched down.

Or had it? The animation had switched to simulation mode in the final 30 seconds, suggesting a loss of telemetry from the lander, or at least a loss of data for the animation. The audience in Tokyo remained quiet as the event’s emcee advised them it could be several minutes before they had information about the lander’s status.

Views of the mission control center showed them quietly staring at screens the audience could not see. One controller put his arm around the shoulder of another, but it was not clear if it was a gesture of reassurance or consolation. “You can really feel the tension,” the emcee said, perhaps unnecessarily.

The minutes stretched to nearly a half hour before ispace broke the inevitable news. “At this moment, we have not been able to confirm a successful landing on the lunar surface,” said Takeshi Hakamada, CEO and founder of ispace. “So, we have to assume that we could not complete the landing on the lunar surface.”

Several hours later, ispace provided a few more details. In a statement, it said that while the lander appeared to be working well until final approach, data showed the available propellant on the lander reached “the lower threshold and shortly afterward the descent speed rapidly increased.” In other words, it appeared the lander ran out of fuel and fell to the surface.

“Based on this, it has been determined that there is a high probability that the lander eventually made a hard landing on the Moon’s surface,” ispace stated. The company has not provided any updates since that statement.

The scene in Tokyo was familiar because it played out almost exactly like what happened four years ago, when Israel’s Beresheet spacecraft attempted a lunar landing: a normal descent, then some confusion about the telemetry, followed by a swift realization that the lander had crashed (see “If at first you don’t succeed…”, The Space Review, April 15, 2019). The same events played out a few months later as India’s Vikram lander crashed while landing on the Moon, although it took longer for India’s space agency ISRO to acknowledge the failure (see “Schrödinger’s lander”, The Space Review, September 9, 2019).

The failed HAKUTO-R M1 landing was just another reminder of how difficult it is to build a spacecraft that can land softly land on the Moon. As a new wave of lunar exploration builds up, the world has a decidedly mixed record in achieving landings on the Moon. China, remarkably, has three successful landings in as many attempts, including the first landing by any nation on the lunar farside and a sample return mission. The rest of the world, though, is batting 0-for-3 so far this century.

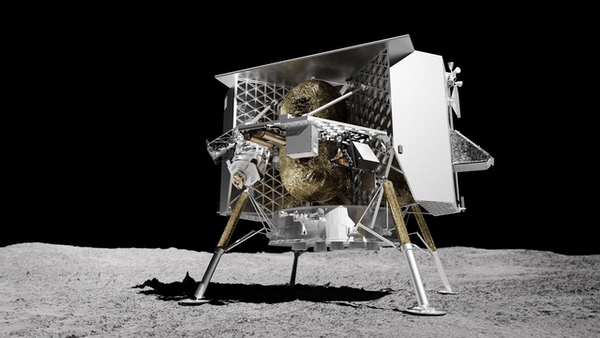

Astrobotic plans to launch its Peregrine lander, its first mission to the Moon, this summer. (credit: Astrobotic) |

Lessons for CLPS

More missions will be attempting landings this year. India will try again with its Chandrayaan-3 mission launching this summer. Japan is launching its first lander, the Smart Lander for Investigating Moon (SLIM), as soon as August. And Russia will launch its first lunar lander mission since 1976 with the long-delayed Luna-25 mission later this year, even if there’s widespread skepticism about its chances for success (see “Russia returns to the Moon (maybe)”, The Space Review, March 13, 2023).

| “Landing on the Moon is very challenging. It’s not easy to do,” Kearns said. “But I will tell you that all of these companies that NASA has awarded particular task orders to to deliver have put great effort into this.” |

The brightest spotlight, though, is likely going to be on American companies backed by NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program. Astrobotic’s Peregrine lander and Intuitive Machines’ IM-1 mission are both scheduled to launch this summer as the first missions by those companies and the first in the overall CLPS program, intended to stimulate the development of lunar landers with NASA as one of potentially many customers.

In fact, if all had gone according to earlier plans, Peregrine would have been launching this week. In February, United Launch Alliance announced it set a May 4 date for the inaugural launch of its Vulcan Centaur rocket, carrying Peregrine as well as two experimental satellites for Amazon’s Project Kuiper broadband constellation. That launch, though, is on hold after a fireball erupted from another Centaur upper stage being tested by ULA at the Marshall Space Flight Center in late March. ULA says it now expects the launch to take place no earlier than June or July.

When the Vulcan carrying Peregrine, and the SpaceX Falcon 9 launching IM-1, do finally lift off, they will put to the test a central tenet of CLPS: a willingness to fail. When NASA started CLPS five years ago, it accepted what agency officials frequently called a “shots on goal” philosophy: just as not every shot in a hockey game or soccer match makes it into the back of the net, not every lander will make it to the lunar surface intact. That was, perhaps, easier to accept at the start of the program, when the record showed successes of the Chinese landers but not yet the failures by other nations.

NASA officials say they are still committed, by and large, to that philosophy. “It was a different level of risk than we were used to,” said Joel Kearns, deputy associate administrator for exploration in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate (SMD), during the National Academies’ Space Science Week in March. “We deliberately did not implement the levels of oversight and insight that NASA normally does.”

That limited insight, he explained, was a deliberate decision to treat the lander as a commercial service, as it does for commercial cargo and crew, despite the lack of experience in lunar landings. “Landing on the Moon is very challenging. It’s not easy to do,” he said. “We’ve seen how challenging it’s been for other parties that have attempted it. But I will tell you that all of these companies that NASA has awarded particular task orders to to deliver have put great effort into this. They’ve learned a lot.”

Jack Burns, an astronomer at the University of Colorado who has a CLPS payload on IM-1, agreed. He said Intuitive Machines was “very open and honest” about issues with the spacecraft’s propellant tanks that delayed its development. “Overall, the experience so far has been good,” he said. “The lessons learned will come, hopefully, after a successful landing.”

There are signs that the CLPS program is maturing even before the first launch. The biggest CLPS mission awarded to date went to Astrobotic, using its larger Griffin lander to deliver the agency’s Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER) mission. Last year, NASA announced it was slipping the launch a year to late 2024 to do more testing of the lander.

“VIPER is NASA’s largest and most sophisticated science payload to be delivered to the Moon through CLPS, and we’ve implemented enhanced lander testing for this particular CLPS surface delivery,” Kearns said last July when the agency announced the delay. NASA said it would pay an additional $67.8 million to cover that work, bringing the total cost of the Astrobotic task order to $320 million.

That seemed a good investment to NASA given VIPER itself costs an estimated $433 million. Speaking at a meeting of the Lunar Surface Innovation Consortium (LSIC) last week, Brad Bailey, assistant deputy associate administrator for exploration at SMD, compared it to buying insurance on a valuable package being shipped. “Having augmented insight gives the higher-ups at NASA a little bit more room to breathe.”

The payloads flying on those landers are also maturing despite the lack of landing experience. “We just needed some high-quality science instruments that we could put on to these early landers to demonstrate the power of the CLPS model,” he said. Now, the agency is putting more focus on developing new payloads.

The agency is being more discriminating regarding the payloads it flies. “When CLPS first started getting stood up, we took all comers,” he said, including from international partners. Now, Bailey said NASA is encouraging those partners to work directly with the CLPS providers to avoid taking away some of the business they could get. “We realize there is an impact on the lunar economy” when NASA offers free rides for those payloads.

| “Ultimately, NASA does not want to be the prime customer for all of these deliveries,” said Bailey, “and we would consider ourselves to be successful when we start to see several of these vendors actually landing on the Moon without NASA payloads.” |

There are signs the industry is also maturing, at least on the business side. Other than VIPER, most initial CLPS missions were valued at less than $100 million, in some cases around $75 million. But the most recent award, won by Firefly Aerospace in March, was worth $112 million. That may be linked, in part, the complexity of the mission: a lander on the lunar farside along with delivery of ESA’s Lunar Pathfinder spacecraft in orbit.

However, it may reflect more realistic pricing for such missions. “We saw the price come up and I’ll be interested to see if that’s going to continue to be the case,” said Alan Campbell, senior program manager at Draper, in a recent interview. Draper won a CLPS task order last July for the program’s first farside landing, valued at $73 million.

“I think the CLPS office has understood that getting the teams in for the first time at lower than cost had some ill effects in one particular case,” he said in an interview. That’s a reference to Masten Space Systems, which won a CLPS award in 2020 but filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy last July and had its assets acquired by Astrobotic. (The CLPS award remains on NASA’s books as the Chapter 11 legal process continues, but the agency says it has contingency plans to move the payloads assigned to that mission to future CLPS landers.)

NASA, he said, may have underestimated the ability of companies to make up for the low bids on NASA task orders with commercial business. Missions are also becoming more complex, driving up costs. NASA’s Bailey said a notional cost of $1 million per kilogram of payload used for early missions likely won’t apply to later ones as NASA introduces more requirements, like the ability to survive the lunar night and offer mobility.

Companies say they’re also finding more success winning commercial business. During a CLPS panel at the LSIC meeting—ironically taking place at the same time as ispace was attempting its landing—Astrobotic announced it signed a contract with SpaceX for a Falcon Heavy launch of a third lander mission in 2026. Unlike the first two, this mission has no ties to NASA’s CLPS program, at least for the time being.

Another panelist, Intuitive Machines chief scientist Ben Bussey, said the company was close to finalizing a lander mission called IMC-1 that would not have any NASA payloads. That would be in addition to its three CLPS missions, IM-1 through -3.

That’s good news for Bailey. “Ultimately, NASA does not want to be the prime customer for all of these deliveries, and we would consider ourselves to be successful when we start to see several of these vendors actually landing on the Moon without NASA payloads.”

Lunar quest

That assumes that those companies will be able to deliver those payloads to the lunar surface. The experience of Israel’s Beresheet, India’s Vikram, and now ispace’s HAKUTO-R demonstrate there are still technical challenges that those companies will likely have to overcome, and higher chances their shots will not go into the goal.

| “We will keep going,” Hakamada vowed. “Never quit the lunar quest.” |

Despite the failed landing, ispace was unbowed. It was already working on its second lander, similar in design to the M1 lander but with some improvements based on lessons learned in the first mission’s development. The company says it’s funded to support that second mission while working on the design of the larger Series-2 lander, which ispace’s US subsidiary is providing to Draper for its CLPS mission. That included money it raised by going public in early April on the Tokyo Stock Exchange; the company’s valuation soared to about $1.3 billion by the time of the landing, only to be cut in half by the end of last week.

“It’s important to feed back what we learned from mission 1 to mission 2 and mission 3,” Hakamada said after announcing the failed landing. “That’s why we built a sustainable business model to continue our efforts for the future missions.”

“We will keep going,” he vowed. “Never quit the lunar quest.”

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

No comments:

Post a Comment