Stonehouse: Deep space listening in the high desertby Dwayne A. Day |

| While it was relatively easy to develop ground stations to detect signals coming from missiles or satellites, the US intelligence community lacked a dedicated ground station for detecting the much fainter signals from Soviet spacecraft heading to the Moon and planets. |

STONEHOUSE was established at Asmara in Ethiopia in 1965, becoming the first site specifically built for the interception of space signals. It was a “deep space” intercept site and played a key role in collecting signals from Soviet spacecraft, including lunar and Venus missions, until it ceased operating in the mid-1970s. STONEHOUSE’s existence was acknowledged by the Department of Defense even before the complex was finished, but information about it has been relatively sparse. The National Security Agency has declassified information on STONEHOUSE in several documents, and over time increasing information on what was collected at the site has also been declassified.[1]

The former Soviet satellite ground station at Yevpatoria, Ukraine, was the location where signals from Soviet lunar, planetary, and communications spacecraft were received. Transmissions from this station were intercepted by an American station located in Turkey, providing information on what was being communicated to the spacecraft. The NSA-operated STONEHOUSE station in Ethiopia intercepted communications sent from the spacecraft to this ground station. This location in Crimea is now illegally occupied by Russia. (credit: via Wikipedia) |

A network of listening posts

By the early 1960s, the NSA began planning for the development of multiple ground stations to intercept Soviet satellite signals in order to both detect and track satellites as well as launch vehicles and missiles. The NSA established the BANKHEAD I station in Peshawar, Pakistan, to cover launches from the Soviet Kapustin Yar launch complex. It established BANKHEAD II in Japan to cover early orbits of satellites launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome as well as ICBM launch telemetry. Both stations began operations in 1962. The NSA also built BANKHEAD III in Turkey. The Turkey ground station was plagued by substantial problems with spare parts supply. It was later renamed HIPPODROME.[2]

Geography was a key factor in locating the intercept stations, and Turkey was a prime spot for listening in on the Soviet space program. The main Soviet ground station for communicating with many space systems was located at Yevpatoria in the Crimean Peninsula in what is currently illegally occupied Ukraine. Yevpatoria was located due north of the BANKHEAD III/HIPPODROME site, which was close enough to intercept the signals being sent from the Crimean station into space.

According to an official history of the program, this network of stations around the world was designed “to be capable of collecting signals from space vehicles, tracking such vehicles, and performing preliminary on site processing of intercepted signals. They were to employ improved, high-speed communications to make near real-time reporting possible.”[3]

A 1962 planning document outlined the requirements for this network of ground stations:

A knowledge of current Soviet interest and activities is needed to evaluate what counter actions may be expected when[Soviet] research and development systems are replaced by operational weapons systems. Requirement requests the following information be provided:

(1) Information indicating that the Soviets intend to physically intercept or destroy a U.S. space vehicle.

(2) Information indicating that the Soviets plan to trigger telemetry readout from a U.S. space vehicle.

(3) Information that the Soviets plan to or are jamming reception of signals from a U.S. space vehicle.[4]

Intelligence analysts noted that Soviet space activities and launch capabilities were increasing rapidly and they could possibly begin orbiting nuclear weapons. Some in the intelligence community were alarmed by “the fact that ‘the U.S.S.R. assuredly possesses the propulsion capability required to place high-yield nuclear warheads in orbit,’ along with a probable requirement for reconnaissance satellites for targeting mobile and deployed Strategic forces.” An NSA planning document quoted North American Aerospace Defense Command’s (NORAD) estimate of the Soviet threat, with the prediction that by late 1964 the USSR could have between 50 and 150 major useful vehicles in Earth orbit. These satellites could include:[5]

| Type | Number in orbit late 1964 |

|---|---|

| Bombardment | 30 |

| Reconnaissance | 60 |

| Communication Command | 40 |

| Jamming | 40 |

| Navigation, Weather, Communication, etc. | 24 |

| Scientific | 12 |

NORAD and the Joint Chiefs of Staff operational commanders also recognized that a great majority of the Soviet military vehicles would be active reconnaissance satellites and mapping satellites. Although the Soviets might try to disguise the real intent of a vehicle, as was the case in other intelligence operations, the NSA planners emphasized that this should not discourage the US from trying to intercept and identify emitted signals.

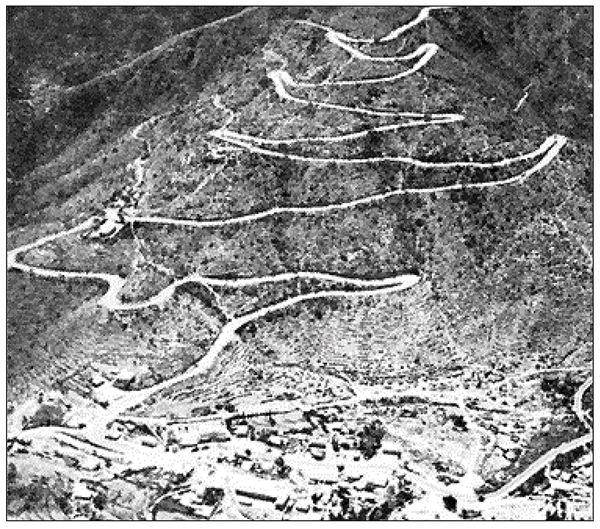

The winding road leading to the STONEHOUSE facility was dotted with crosses marking where Italians had crashed their cars when Italy occupied Ethiopia before losing it to the British in 1941. (credit: NSA via Cryptologic Quarterly) |

Creation of STONEHOUSE

A small Italian radio relay station had been established in Asmara, Ethiopia, during World War II. Asmara was an ideal site because it was located 2,300 meters (7,600 feet) above the Red Sea, enabling the station to transmit over long distances. The Italian government surrendered the capital city in 1941 and the British occupied the site for a short time before turning it over to the US Army, which established a radio station there in 1943. In May 1953, the United States signed a 25-year lease agreement with the Ethiopian government, and the station was formally designated “United States Army Radio Station: Kagnew Station,” or simply “Kagnew Station” for everybody who lived there.[6]

| STONEHOUSE was patterned after the NASA “deep-space instrumentation facility since the data to be collected was similar.” |

Kagnew Station became a relatively large facility providing support to two Army Security Agency stations, a US Navy communications station, a US Army strategic communications Defense Communications Agency facility, a communications facility for the Diplomatic Telecommunications Service, and the US Consulate General in Asmara. Post housing was also located at the site. The sites of the various communications-related stations and support elements were referred to as “tracts.” Tract A, located in downtown Asmara, was used for post housing. Tract B contained DCA and Navy facilities, and Tract E was the main post. Tract C was known as the Operations Site. It was located west of Tract E, and its large antenna field was euphemistically referred to as “the funny farm.” The site operated 24 hours a day.

In 1960–1961, the NSA developed the Space Surveillance Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) Program “in an effort to provide an adequate U.S. collection capability to meet high priority SIGINT requirements related to Soviet space activities,” according to a history of the program.[7] Some space collection systems could be placed at existing American military bases, but others might require entirely new sites.

The NSA had already achieved success intercepting signals from Soviet spacecraft, starting with Sputnik. When Yuri Gagarin was launched into orbit in April 1961, the US intelligence community was waiting. They had previously collected and analyzed TV signals from an earlier canine flight at sites in Turkey and Iran, which led the intelligence community to prepare to collect future TV signals. When Gagarin’s spacecraft went into orbit, American facilities at Shemya, Alaska, and Helemano, Oahu, Hawaii, were provided with special equipment and intercepted TV signals indicating there was a man inside the Vostok.

The original Space Surveillance SIGINT Program submission to the Department of Defense was to establish several different ground sites for the interception of space signals. A system known as BANKHEAD was to be built in Pakistan, Japan, and Turkey. But while it was relatively easy to develop ground stations to detect signals coming from missiles on ballistic trajectories, or satellites in low Earth orbit, the US intelligence community lacked a dedicated ground station for detecting the much fainter signals from Soviet spacecraft heading to the Moon and planets.

According to James Burke, who had worked at JPL on the Ranger lunar program and then went to work for the US intelligence community tracking Soviet spacecraft, numerous US intelligence agencies, including the Defense Special Missile and Aeronautics Center, the CIA’s Office of ELINT, and NSA and CIA contractors, kept track of Soviet deep space activities.[8] “It was hard to show a direct connection between such intelligence and national security,” Burke wrote. But because there was a possibility of the United States and Soviet Union combining their space efforts, particularly flights to the Moon, better tracking of Soviet planetary missions was useful. There was also the puzzling fact that the Soviets were launching a lot of spacecraft to the Moon and elsewhere.[9]

“The main product of our intelligence effort is not the pictures, it is the insight we have gained into the Soviet deep-space program as a whole,” Burke added. As he explained in a 1966 article, the level of effort by the Soviets was large, and therefore mysterious. Why were they sending so many planetary spacecraft to the Moon, Mars, and Venus? Between 1960 and 1966, the Soviet Union had launched nearly 40 planetary space missions. During the same period, the United States had only launched 14.[10]

The need to detect signals from Soviet craft in deep space led to the NSA’s plan to develop the STONEHOUSE network of deep space tracking stations. Three STONEHOUSE facilities were to be built. Although the locations of two of the proposed facilities are still classified, they were justified in part because the Soviet Union was seeking to locate ground stations in South America, Australia, and possibly Africa—so the proposed STONEHOUSE stations would have been located relatively nearby. However, planners acknowledged that the Soviets might also use a “dump method” of returning data only when the spacecraft were in view of the USSR, rather than deploying stations around the world.

Due to costs, the plan for three STONEHOUSE sites was scaled back and only one STONEHOUSE system was to be built, located in Africa. In another cost-cutting measure, the BANKHEAD systems would not receive all their planned equipment.[11]

A deep space interception station would require a large antenna, a highly sensitive receiver, and high-quality recording devices. It would also ideally be sited in a location free of radio noise. STONEHOUSE was patterned after the NASA “deep-space instrumentation facility since the data to be collected was similar.”[12] Although the plan had originally been for three STONEHOUSE stations, Burke noted that because the Soviets only transmitted during the time when the spacecraft was in view of the Crimean station—the so-called “dump method”—the US only needed one station of its own, and although the other two stations were eliminated because of cost, they proved to be unnecessary.[13]

The BANKHEAD system in Turkey, which was eventually renamed HIPPODROME, was apparently tasked with cueing STONEHOUSE about Soviet planetary launches so that STONEHOUSE could later intercept their data.[14]

| The American interceptions of Soviet transmissions from Luna 9 were better than what the Soviets themselves received. |

The original STONEHOUSE plan was a single 26-meter (85-foot) diameter antenna, but a 46-meter (150-foot) diameter antenna was later added for redundancy. The larger antenna had lower surface quality but simpler construction.[15] The contract was awarded to Radiation, Incorporated, of Melbourne, Florida, on August 1, 1963.[16]

It was impossible to hide such large antenna dishes, and their construction would attract attention. In January 1964, the Department of Defense issued a news release that acknowledged their existence, but referred only euphemistically to their mission:

Experimentation in the peaceful uses of space will receive added impetus in Africa with the installation, at Kagnew Station, of additional equipment for space communications research and for future study of radio receiving and transmitting techniques. The new equipment, now ready for installation, will consist of two rotatable parabolic antennas, one 26 meters (85 feet) in diameter and the other 46 meters (150 feet) in diameter. These modern antennae are designed to further the study of long-range communications and to facilitate the study of the effects of the ionosphere on communications.

The selection of Asmara for this important new space research activity resulted from extensive surveys to find an area combining relatively quiet electronic environment, and suitable topographic features and climate characteristics, near the equatorial belt. Kagnew Station is a particularly appropriate site to receive the new antennas in light of the station’s past contributory research into natural electronic phenomena. The new equipment will expand Kagnew's communications research capability and will permit scientific measurement of unusual transmission characteristics in outer space communications research. United States interest in this research activity is based on the desire to improve long-range communications world-wide.

The new installation will make an important contribution to man's expanding knowledge of the mysteries of outer space. Materials for the new antennas will begin to arrive at the seaport of Massawa in early May. From there, they will be truck-hauled to Asmara. The installation is expected to be completed in 1965 and during phases of its construction should employ many Ethiopian workers. Arrangements will be made for groups of visitors to tour the new facility during its construction in accordance with past practice at other parts of Kagnew Station.[17]

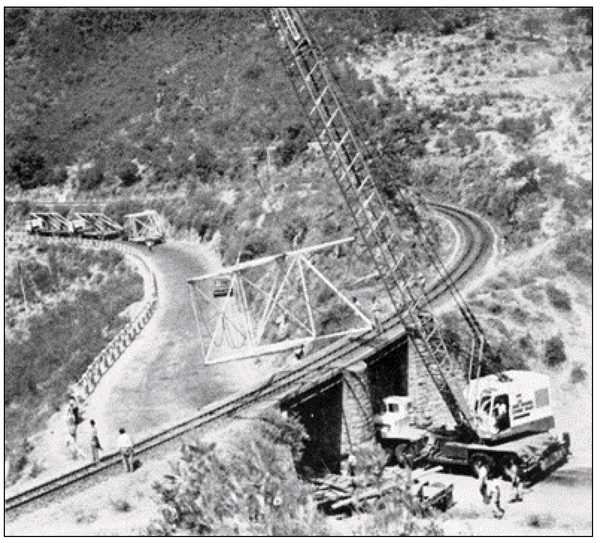

In 1964–1965, significant amounts of new equipment began arriving from the United States at the Ethiopian port of Massawa. The site equipment, including construction equipment, had to travel along the treacherous Asmara-Massawa road, which was marked with numerous crosses where car-racing Italians had met their deaths more than two decades earlier. At some points along the road large structural pieces for the antennas had to be lifted off their trucks by crane, swung over bridges, and then set back on the trailers for continued transport to the site.[18]

Once the equipment was taken to the location, it was erected to build the two large radio antenna dishes. But construction was not always easy. At one point a forklift sank into the ground during installation of the larger antenna. A worker wrote on a photograph of the incident, “After this we should have quit. We didn’t. Motor pool to the rescue.”[19]

Construction of the large dishes required shipping in equipment and supplies, and sometimes lifting it over bridges to get to the site. (credit: NSA via Cryptologic Quarterly) |

Deep space tracking before STONEHOUSE

James Burke noted that the Soviets had very small launch windows to the planets, which made predicting and tracking the launches easier for the Americans.[20] In some cases, missed launch windows gave the Americans the opportunity to better prepare for intercepting signals on the next attempt.

| According to Burke, during nearly a decade of operation, “STONEHOUSE functioned with increasing competence, recording signals from Soviet lunar missions, comsats, and planetary spacecraft.” |

In February 1963, the Soviet Union launched a lunar spacecraft, which failed to reach orbit. They skipped a March launch opportunity, but followed it with the Luna 4 mission in April. By this time, the NSA had borrowed a large dish in Maryland—operated by the Naval Research Laboratory and nearly identical to the 150-foot dish planned for STONEHOUSE—and pointed it at the spacecraft’s location. It was able to intercept signals from the Soviet craft. Because of its location in the eastern United States, however, it could only receive the last part of the spacecraft’s transmission to the Crimean ground station. But this limited intercept was a major intelligence coup for the United States.[21]

In November 1964, the Soviet Union launched two spacecraft to Mars. One of them failed, but the other left Earth orbit. Although STONEHOUSE was not completed, the NSA had successfully linked several relevant ground sites that were able to tip each other off to launch events, and STONEHOUSE was able to intercept telemetry from the Mars spacecraft. The agency was also able to intercept the powerful command signals being sent up from Crimea.[22]

In May 1965, the Soviet Union launched another mission to the Moon. Although STONEHOUSE was still not yet fully operational, James Burke wrote that “Luna 5 gave the Asmara station its first real chance to perform.” He added that “the station intercepted both of the two spacecraft signals several times during the mission, and both Asmara and Jodrell Bank were listening during the final approach to the moon.” An official history stated that “The result was considered to be high-quality intelligence product of significant consumer interest.” In July 1965, the Soviet Union launched Zond 3, which transmitted photos as it flew past the Moon, photographing the far side. Because the Soviet Union used a photographic technique that sent the signal back on a low-bandwidth link, the Americans could intercept it relatively easily.[23]

STONEHOUSE operations

The STONEHOUSE installation was accepted from the contractor on May 17, 1965, and testing started immediately. But testing was apparently interrupted at several times to focus on operational (i.e. Soviet) targets. Testing work continued throughout the year and by November and December normal operating procedures for maximizing performance were developed.[24]

Serious hydraulic problems were experienced with the smaller antenna. But STONEHOUSE was having other problems, primarily with a lack of spare parts and a maintenance approach that treated every breakdown as a crash repair effort rather than planning for regular and preventative maintenance of equipment. Part of the problem was that STONEHOUSE was unlike any other NSA listening post, but the NSA did not treat it differently than other stations around the world.[25]

When the Soviet Union began operating communications satellites in very high, “Molniya” type orbits starting in April 1965, STONEHOUSE was able to intercept their signals as well.[26] These satellites may have become the primary target for STONEHOUSE in later years, possibly more important than the rare planetary missions.

A major early accomplishment occurred when STONEHOUSE collected information from the Soviet Luna 9 mission. In January 1966, the Soviet Union launched Luna 9, which became the first spacecraft to soft-land on the Moon and return a photo from the lunar surface. STONEHOUSE was able to receive and process this signal. The American interceptions of Soviet transmissions from Luna 9 were better than what the Soviets themselves received.[27]

Other telemetry data from orbiting Soviet satellites was collected from the BANKHEAD stations. For instance, another site collected important information from the Soviet Union’s prototype navigation satellite Cosmos 192, launched in 1967.[28]

Although there is no public information about it, STONEHOUSE would certainly have been focused on collecting data from the series of Soviet Lunokhod rovers that operated on the Moon from 1969 to 1973. The United States did not operate any similar spacecraft. However, the data collection from the rovers might have been less than ideal because of limitations in American collecting capabilities.

James Burke was involved in processing the data collected from STONEHOUSE and in 1978 he wrote a classified article for the CIA’s in-house journal, Studies In Intelligence, about the inability to find a signal from Soviet deep space missions that the Americans knew existed, a planetary broadband signal that relayed video imagery and science data to the ground. The NSA knew about this signal because the Soviet Union had publicly acknowledged that they had such a link, and released imagery such as a picture of Mars taken by the Mars 5 spacecraft in 1973. It was obviously there, but the NSA could not detect it.[29]

According to Burke, during nearly a decade of operation, “STONEHOUSE functioned with increasing competence, recording signals from Soviet lunar missions, comsats, and planetary spacecraft.” The site “with the aid of several collaborating sites, gave us a fairly full understanding of the Soviet lunar and planetary program.” Not only did the NSA learn how the known data links worked, “we even obtained some scientific data superior to any released by the Soviets, indicating that STONEHOUSE was performing as well or better than the Soviet Crimean deep-space stations, at least for the decimeter-wave, narrow-band telemetry.” But they were still thwarted: “In all this time, however, we never acquired the centimeter-wave, broad-band signal. We came to know exactly where to look and when to expect it to be on the air; we thought we knew its approximate frequency; we searched and did not find it,” Burke wrote.[30]

| At one time STONEHOUSE was tasked with tracking a US spacecraft after launch. However, when they could not detect it, STONEHOUSE operators became concerned that they had made a mistake and missed the satellite. They later learned that the launch had in fact gone off course and they could not have detected it after all. |

To a layperson, it might not seem like a tough task, because the spacecraft was sending its signal back to the ground and STONEHOUSE could point in its direction. Burke explained that it was not a simple thing to do: “The problem in such searches is that one seeks a small needle in a large haystack. The search dimensions are space, time, and frequency. In space, one must point the receiving antenna precisely toward the signal source. We had to determine the trajectory of each outbound spacecraft soon after it left Earth, so that we would know where to point the antennas during the months of interplanetary flight. This was done with the aid of radar tracking from Diyarbakir in Turkey and sometimes with angle tracking, either radio or optical, from sites in Iran and California.”[31]

They could not search continuously whenever the spacecraft was in view because this would be too costly. They therefore observed other signals and devised schemes to concentrate their searches at the right times. They were aided by a site in Turkey (most likely HIPPODROME) that intercepted Soviet deep-space command uplink transmissions from Crimea.[32]

According to Burke, the overseas sites were tied into a real-time system using computers and secure communications. “Though often plagued by communications problems, this system essentially solved the space and time search problems. This left the frequency dimension, which was and remains the chief obstacle.”[33]

Burke did not think that the Soviets were engaging in deliberate deception. “In other parts of their deep-space enterprise they seem to have followed a fairly consistent pattern: reluctance to release information before launch, lack of candor about failures, and accurate but incomplete information about successes. Outright lies appear to have been rare.”[34]

Soviet-released circumstantial evidence was used to guide the American search. One clue was obtained when US intelligence agents physically measured the waveguide connected to an antenna on a Zond 3 spacecraft mockup displayed at the Montreal EXPO-67. However, spacecraft observed at exhibits in Paris and Moscow in 1974 had different equipment, and eventually the analysts concluded that the equipment had been evolving and the exhibits had been pieced together from existing, possibly obsolete, equipment that was available. Accurate data was not obtained until 1977. Nevertheless, despite narrowing the search even more through various means, by 1978 they still had not located the frequency.[25]

Burke admitted that this was not a major intelligence failure. But he also explained why the intelligence services were interested in obtaining data from Soviet deep-space missions. “The whole problem is more an annoyance than a crisis. Soviet planetary results have seldom been of primary importance to the United States and, when unique data are obtained, they are eventually published in the scientific literature. Because of the relatively low priority of orbital planetary imaging in the Soviet program, our own planetary mapping has been much better than theirs. And yet there may be valid reasons for pursuing the search. In both our program and theirs, the tendency has been for communication links to move upward in frequency with time: as technology has advanced, more efficient links can be designed for shorter and shorter wavelengths. If the centimeter-band signal ever replaces the decimeter-band ones in the Soviet scheme and we have not yet found it, even our present limited source of prompt and objective deep-space information will disappear. Also, any such search is an exercise of techniques that have other uses. Should it turn out that the Soviets have been deliberately hiding the signal by any of several possible spread-spectrum or suppressed-carrier techniques, we will have learned something important. There is some evidence that a similar signal may be in use as a privacy link from certain Soviet Earth satellites.”[36]

In addition to its mission of collecting Soviet signals, STONEHOUSE also had a secondary mission supporting US space operations. According to one history, at one time STONEHOUSE was tasked with tracking a US spacecraft after launch. However, when they could not detect it, STONEHOUSE operators became concerned that they had made a mistake and missed the satellite. They later learned that the launch had in fact gone off course and they could not have detected it after all.[37]

In early 1975, STONEHOUSE had to be hastily abandoned. Classified and sensitive documents were burned outside the facility. (credit: NSA via Cryptologic Quarterly) |

Closure of STONEHOUSE

The BANKHEAD stations were capable of collecting substantial information from Soviet satellites. In addition to the first three stations, located in Pakistan, Japan, and Turkey, the BANKHEAD IV station was planned to be established on Shemya Island, in the Aleutians chain, and BANKHEAD V was to be built at a location that is deleted from official histories, but was most likely Hawaii. But costs were growing and one estimate indicated that BANKHEAD IV and V would be 25% of the overall cost of the system while producing 16% of the system requirements. BANKHEAD IV was going to be built at a location where no current military base existed, which would have increased the cost of construction. So, BANKHEAD IV was canceled and the requirement was subsequently met by equipment installed as part of the ANDERS project. Another station was originally named BANKHEAD V, but the name was changed to JAEGER.[38]

One of the inherent drawbacks of American ground stations located on foreign soil was that they were subject to political changes. The BANKHEAD I station in Peshawar, Pakistan, was dropped from the SIGINT Space Surveillance Program by June 1966 due to political considerations. The ten-year lease for the site expired in 1968 and was not renewed, and the site was closed and evacuated by 1970.[39]

| In 1974 civil war broke out in Ethiopia. The conflict reached Asmara on January 31, 1975, and local conditions quickly deteriorated. |

At its peak, the American military and civilian community in Asmara numbered about 6,000 persons, including dependents—there was even a 17-classroom school for dependents’ children. But in the late 1960s and early 1970s, many of the resident organizations decreased their activities and began withdrawing personnel.[40] In contrast to the thousands working at the other facilities and their dependents, STONEHOUSE was a relatively small facility manned by eight civilians and 43 military personnel.[41]

Operations on Tract C ceased in March 1972. Following the departure of the Army, the Navy assumed the headquarters function and, in 1973, NAVTELCOMM assumed control, renaming Kagnew Station as NAVCOMMSTA Asmara. Soon the Navy assumed the functions of the Army STRATCOM facility, but the Navy was also planning to reduce its activities. While the Navy was phasing out its operations, Tract A was turned over to the Ethiopian government, and subsequently used by the Ethiopian Navy.[42]

The result of the reduction in activities and personnel was that STONEHOUSE, which had started as a relatively small—albeit visibly prominent—installation, eventually became the largest US organization in Asmara. This also forced STONEHOUSE to become self-sufficient. According to a declassified history, by mid-January 1975, most of the problems had been overcome, and the facility was ready to operate independent of outside logistical support.[43] That independence was both timely, and ironic, because the station’s operations would quickly be cut short.

In 1974 civil war broke out in Ethiopia. The conflict reached Asmara on January 31, 1975, and local conditions quickly deteriorated. Most dependents were sent home as quickly as possible; those remaining took up temporary residence at the consulate, and at the STONEHOUSE facility itself.[44]

The facility personnel had to quickly plan for the abandonment of the site. They created burn piles to dispose of classified documents, including files, manuals, documents, and tapes that might provide insight into the STONEHOUSE mission or operations.

A more difficult challenge was destroying the equipment. KW-26 cryptographic equipment was not in active use and was the first designated for destruction. The KG-13 cryptographic key generators were next to be destroyed along with all other cryptographic material. Last up was the KW-7s, which were still being used to protect the primary communications link to the American consulate.[45]

The destruction of some of the equipment presented problems. The metal casings for some electronic equipment was burned, but base personnel discovered that some pieces of equipment remained identifiable, including ID plates that designated the equipment, its security classification, and the name of the National Security Agency.[46]

Classified equipment at STONEHOUSE was smashed and burned as the facility was being abandoned. Some identifying marks were still visible even after this attempted destruction. (credit: NSA via Cryptologic Quarterly) |

The evacuation also required the transport of significant equipment and personal property out of the country. “Over 100 crates were packed with operations items, and then attention was turned to personal goods. (During this period, the facility ran out of packing material for the operations equipment and materials, and more had to be ordered and shipped from the U.S. by air at considerable expense.) All available vehicles, including the school bus and ambulance, were used to transport household items to the STONEHOUSE facility for safekeeping, as thievery was by then a serious problem. Later, the operations equipment and household goods, along with other personal possessions, were shipped by a local company to the airport in Addis Ababa for transportation back to the United States. Evacuation of operations personnel followed, and by February 21 only eight Americans of the original nearly 6000 personnel remained in Asmara: three from NSA and five from contractors. They stayed to handle the remaining packing, crating, and transportation matters.”[47] Fortunately, most of what the NSA had requested be saved was saved.[48]

On March 4, 1975, STONEHOUSE was officially disestablished. Only three people remained behind—a radio operator, a teletype repairman, and a doctor—to support remaining State Department and Navy personnel.[49] Kagnew remained active until 1977, when the last Americans left. In addition, the HIPPODROME site in Turkey was shut for three years after the United States imposed an arms embargo on that country.

| STONEHOUSE was the only NSA-operated facility in the proper location to receive the data from Soviet deep space vehicles. Its loss prompted a search for an alternative source, ultimately resulting in the NSA turning to their British counterpart, GCHQ. |

According to an official history, the loss of STONEHOUSE “was not as significant as might otherwise have been the case. Although prematurely closed in 1975, it had been scheduled for closure in June 1976, mainly because of the unstable situation in Ethiopia and the evolving threat of civil war. Consequently, the establishment of other such facilities and functions elsewhere had long been planned, and to a degree implemented, by the time STONEHOUSE was closed.”[50]

A few years after the STONEHOUSE closure, the Iranian revolution forced the CIA to leave its TACKSMAN sites there. Those sites were focused on Soviet missile and rocket launches, although they may have had some ability to monitor low Earth orbit satellite communications. These losses, combined with the closure of the Pakistan site in the 1960s, and the interruption in operations in Turkey starting in 1975, presented major setbacks for American telemetry interception efforts. STONEHOUSE was the only NSA-operated facility in the proper location to receive the data from Soviet deep space vehicles. Its loss prompted a search for an alternative source, ultimately resulting in the NSA turning to their British counterpart, GCHQ, to provide the intelligence. Although details remain classified, Britain retains a signals intelligence station in Cyprus, due north of Asmara—and even closer to Yevpatoria, Ukraine.[51]

Today the former STONEHOUSE site is located in the relatively new country of Eritrea. Although the large dishes are gone, it is used as a satellite communications center.

Endnotes

- Richard L. Bernard, The Foreign Missile and Space TELEMETRY Collection Story – The First 50 Years Part 2, “Chapter 2, Expansions to Meet Increasing Workload (1970s),” p. 29.

- Richard L. Bernard, The Foreign Missile and Space TELEMETRY Collection Story – The First 50 Years, Part 1, “Chapter 2, The SPACOL Plan and DEFSMAC (Early 1960s),” p. 32; H.D. Wagoner, “Space Surveillance SIGINT Program,” United States Cryptologic History, Special Series #3, National Security Agency, 1980, p. 38.

- H.D. Wagoner, p. 1.

- H.D. Wagoner, p. 5.

- H.D. Wagoner, p. 9.

- Mark Nixon, “The STONEHOUSE of East Africa,” Cryptologic Quarterly, Center for Cryptologic History, 2019-01, Vol. 38, p. 29.

- H.D. Wagoner, “Space Surveillance SIGINT Program,” United States Cryptologic History, Special Series #3, National Security Agency, 1980, p. 1.

- James Burke, “Seven Years to Luna 9,” Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 10, Summer, 1966, p. 1.

- Ibid., p. 10.

- Ibid., p. 3; 5.

- H.D. Wagoner, “Space Surveillance SIGINT Program,” United States Cryptologic History, Special Series #3, National Security Agency, 1980, p. 1; 11.

- Ibid., p. 18.

- James Burke, “Seven Years to Luna 9,” Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 10, Summer, 1966, p. 10.

- H.D. Wagoner, “Space Surveillance SIGINT Program,” United States Cryptologic History, Special Series #3, National Security Agency, 1980, p. 14.

- James Burke, “Seven Years to Luna 9,” Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 10, Summer, 1966, p. 11.

- H.D. Wagoner, “Space Surveillance SIGINT Program,” United States Cryptologic History, Special Series #3, National Security Agency, 1980, p. 20.

- Courtesy of Sven Grahn: http://www.svengrahn.pp.se/trackind/Deepspac/Stoneh.htm

- Mark Nixon, “The STONEHOUSE of East Africa,” Cryptologic Quarterly, Center for Cryptologic History, 2019-01, Vol. 38, p. 29.

- Ibid., p. 29.

- James Burke, “Seven Years to Luna 9,” Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 10, Summer, 1966, p. 7.

- Ibid., p. 14.

- Ibid., p. 16; H.D. Wagoner, “Space Surveillance SIGINT Program,” United States Cryptologic History, Special Series #3, National Security Agency, 1980, p. 34.

- James Burke, “Seven Years to Luna 9,” Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 10, Summer, 1966, p. 18; H.D. Wagoner, “Space Surveillance SIGINT Program,” United States Cryptologic History, Special Series #3, National Security Agency, 1980, p. 20.

- H.D. Wagoner, “Space Surveillance SIGINT Program,” United States Cryptologic History, Special Series #3, National Security Agency, 1980, p. 35.

- Ibid., pp. 35-37.

- Information that STONEHOUSE was also intended to collect communications satellite signals is from James D. Burke, “The Missing Link,” Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 22, Winter 1978, p. 3. Burke noted that the communications signals were “of possible military importance.” This is also mentioned in H.D. Wagoner, “Space Surveillance SIGINT Program.”

- James Burke, “Seven Years to Luna 9,” Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 10, Summer, 1966, pp, 20-21; 1.

- Richard L. Bernard, The Foreign Missile and Space TELEMETRY Collection Story – The First 50 Years Part 1, “Chapter 3, The Major Systems and Early Results (Late 1960s),” p. 65.

- James D. Burke, “The Missing Link,” Studies in Intelligence, Vol. 22, Winter 1978, p. 3.

- Ibid., pp. 3-4.

- Ibid., p. 4.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 5.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 9.

- Mark Nixon, “The STONEHOUSE of East Africa,” Cryptologic Quarterly, Center for Cryptologic History, 2019-01, Vol. 38, p. 29. “STONEHOUSE – First U.S. Collector of [deleted] Signals” also mentions a second mission for the site, referring to the support of U.S. spacecraft.

- H.D. Wagoner, “Space Surveillance SIGINT Program,” United States Cryptologic History, Special Series #3, National Security Agency, 1980, p. 17, 32; Richard L. Bernard, The Foreign Missile and Space TELEMETRY Collection Story – The First 50 Years, Part 1, “Chapter 3, The Major Systems and Early Results (Late 1960s),” p. 55.

- H.D. Wagoner, “Space Surveillance SIGINT Program,” United States Cryptologic History, Special Series #3, National Security Agency, 1980, p. 37.

- “STONEHOUSE – First U.S. Collector of [deleted] Signals.”

- H.D. Wagoner, “Space Surveillance SIGINT Program,” United States Cryptologic History, Special Series #3, National Security Agency, 1980, p. 35.

- “STONEHOUSE – First U.S. Collector of [deleted] Signals.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Mark Nixon, “The STONEHOUSE of East Africa,” Cryptologic Quarterly, Center for Cryptologic History, 2019-01, Vol. 38, p. 29.

- “STONEHOUSE – First U.S. Collector of [deleted] Signals.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Richard L. Bernard, The Foreign Missile and Space TELEMETRY Collection Story – The First 50 Years Part 2, “Chapter 2, Expansions to Meet Increasing Workload (1970s),” p. 30; Part 2, “Chapter 3, Improved Worldwide Performance (1980s),” p. 58.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

No comments:

Post a Comment