Since I was a young child Mars held a special fascination for me. It was so close and yet so faraway. I have never doubted that it once had advanced life and still has remnants of that life now. I am a dedicated member of the Mars Society,Norcal Mars Society National Space Society, Planetary Society, And the SETI Institute. I am a supporter of Explore Mars, Inc. I'm a great admirer of Elon Musk and SpaceX. I have a strong feeling that Space X will send a human to Mars first.

Saturday, October 30, 2021

Friday, October 29, 2021

Wednesday, October 27, 2021

Creating A Legal Framework For Natural Resources Development In Outer Space

The scarcity of lunar resources like volatiles illustrates the need to deconflict activities on the Moon in a way that is acceptable by all participants. (credit: NASA) |

Is outer space a de jure common-pool resource?

by Dennis O’Brien

Monday, October 25, 2021

As 2021 comes to a close, humanity is facing a historical crisis, when just a slight change will lead to widely different futures. The closest parallel occurred five centuries ago, when countries with advanced technology sought to exploit the resources of “new” worlds. The resulting Age of Imperialism was marked by needless war, suffering, and neglect, whose effects are still being felt today. How close are we to repeating that pattern? What role can space law play in avoiding it?

| Article II of the OST creates a de jure common-pool resource of outer space and that all subsequent norms, agreements, and activities are subject to it. Any act of exclusion, even for “safety zones,” violates Article II. |

As accessing and developing outer space resources becomes more feasible, determining the status of those resources under international law and norms becomes more important. The oldest and most widely accepted binding international treaty is the Treaty On Principles Governing The Activities Of States In The Exploration And Use Of Outer Space, Including The Moon And Other Celestial Bodies, aka the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 (OST). The most recent proposed norms are the Artemis Accords (Accords), an inter-agency agreement adopted by NASA and its partners as part of the Artemis Moon program. This article concludes that Article II of the OST creates a de jure common-pool resource of outer space and that all subsequent norms, agreements, and activities are subject to it. It further concludes that any act of exclusion, even for “safety zones,” violates Article II and defeats the common-pool resource. It proposes that sharing access to resources will mitigate the exclusion, maintain the common-pool resource of outer space, and allow resource development activities, including the removal of materials in place (in situ). Finally, it will consider whether the Moon Treaty, with an implementation agreement based on sharing and cooperation, can enhance the development of outer space resources, including the building of permanent settlements.

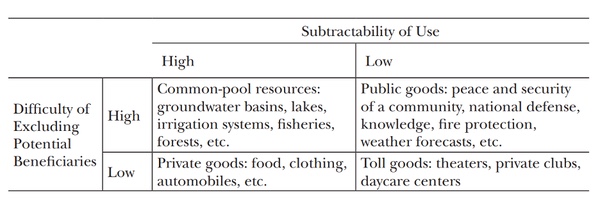

The four categories of goods and resources

Economist Elinor Ostrom received the Nobel Prize in 2009 for her work describing categories of goods/resources. She divided them into four categories depending upon two factors: are they excludable and are they subtractable (aka rivalrous)? She created a grid to demonstrate her analysis:[1]

Figure 1 |

A Private Resource is one that is both 1) excludable, i.e. an entity/group can exercise private property rights, preventing others from accessing/using the resource; and 2. Subtractable (or rivalrous), i.e. use/consumption by one entity/group necessarily reduces the amount available for use/consumption by others. Examples include food, clothing, and automobiles. A more relevant example is an exclusive claim to the mining, recovery, or utilization of a resource.

At the other end of the spectrum are Public Resources, sometimes called a Commons. They are both non-excludable (anyone can access/use them) and non-subtractable (use by anyone does not subtract from the availability of the resource for use by others.) Examples include free-to-air television, open-source software, and, in outer space, solar energy.

In between Private and Public Resources are Toll (or Club) Resources and Common-Pool Resources. A Toll/Club Resource is like a Private Resource in that it is excludable to those who are not members of the club, but it is not subtractable to those entities who are members of the club, i.e., use will not deplete the resource or make it less accessible to other club members. A prime example is paid satellite communication services (video, sound, data, GPS.) No matter how many entities use them, they are still available to those who pay the toll.

A Common-Pool Resource, by contrast, is not excludable; it can be accessed/used by any person, entity, nation, or group of nations. But it is also subtractable: use by anyone means less to use by anyone else unless there is some way to replenish the resource. On Earth these include resources that are beyond the exclusive claim of any national jurisdiction, such as ocean fishing stocks and undersea mineral deposits. In outer space, they include water ice in eternally dark craters, peaks of eternal sunlight that can harvest solar energy (the peaks themselves, not the sunlight), favorable locations for habitats (e.g., proximity to the poles or lava tubes), and mineral-rich asteroids.

| Article II’s prohibition against appropriation means that no State Party can claim exclusive ownership or right of use of any location or resource in outer space. Exclusion equals appropriation. |

Ostrom noted that “This basic division [between private and public goods] was consistent with the dichotomy of the institutional world into private property exchanges in a market setting and government-owned property organized by a public hierarchy.” Her contribution: “Adding a very important fourth type of good – common-pool resources – that shares the attribute of subtractability with private goods and difficulty of exclusion with public goods.”[1] Thus the title of her lecture: Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems.

The non-excludability of space resources

But why are outer space resources non-excludable? Throughout history, sovereign states have claimed such resources for their exclusive use, usually on a first-come, first-served basis. This process was accelerated during the Ages of Exploration, Colonialism, and Imperialism of the past five centuries. It continues today in the Arctic as more resources become accessible. Within nations, under national laws, individuals and corporations have established exclusive claims to resources through discovery, access, and use. Why can’t sovereign states and their nationals do the same concerning outer space resources?

The answer is the Outer Space Treaty. It entered into force on October 10, 1967. As of 2021, it has 111 States Parties, including all spacefaring countries. It has been called the “Constitution of Space Law” and is the basis of all discussions for the governance of humanity’s future in outer space.

The section of the OST that is most relevant to the current discussion is Article II, which states in its entirety:

Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.[2]

Article II’s prohibition against appropriation means that no State Party can claim exclusive ownership or right of use of any location or resource in outer space. Exclusion equals appropriation. By prohibiting exclusion, the ban on appropriation creates a de jure (by law) common-pool resource of outer space.

This prohibition against exclusion also applies to any national of a State Party, i.e., any individual, corporation, or any other private or public entity:

Article VI: States Parties to the Treaty shall bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, whether such activities are carried on by governmental agencies or by non-governmental entities, and for assuring that national activities are carried out in conformity with the provisions set forth in the present Treaty.[2]

The problem with the Artemis Accords

The Artemis Accords seek to facilitate the use of outer space by allowing entities to remove materials from “in place”, thereby acquiring private property rights in the materials:

SECTION 10 – SPACE RESOURCES

2. The Signatories emphasize that the extraction and utilization of space resources, including any recovery from the surface or subsurface of the Moon, Mars, comets, or asteroids, should be executed in a manner that complies with the Outer Space Treaty and in support of safe and sustainable space activities. The Signatories affirm that the extraction of space resources does not inherently constitute national appropriation under Article II of the Outer Space Treaty, and that contracts and other legal instruments relating to space resources should be consistent with that Treaty.[3]

Countries including the United States, Japan, and Luxembourg have passed national laws that grant private property rights to their nationals who extract and utilize space resources.[4] The Agreement Governing The Activities Of States On The Moon And Other Celestial Bodies, aka Moon Treaty, also distinguishes the ban against owning resources in place from ownership once they are removed:

3. Neither the surface nor the subsurface of the moon, nor any part thereof or natural resources in place, shall become property of any State, international intergovernmental or non- governmental organization, national organization or non-governmental entity or of any natural person.[5] [emphasis added]

But the Artemis Accords go further than granting property rights to resources that are no longer in place. They establish exclusive zones for space resource activity, an action that is not widely accepted.[6] Though they are given the innocuous title of “safety zones,” they nevertheless rely upon exclusion. They do so in Section 11, “Deconfliction of Space Activities,”[3] in the following manner:

- They establish a unilaterally declared size for the zone that depends on the nature of the activity, but without any other limitations (Paragraph 7(a)). An entire eternally dark crater could be designated a zone of activity for removing all the water ice there.

- They are unlimited in duration, ending only when the resource activity is completed (7(c)). This would exclude any other party from accessing the resource until it was totally depleted.

- Any effort by another party to access resources in the unilaterally declared zone is deemed to be “harmful interference” and a violation of Article IX of the OST.

| Sharing access to resources mitigates the exclusive nature of the zones; there would be no violation of the Article II prohibition against appropriation. |

Exclusion by any other name, including safety, is still exclusion, and exclusion is appropriation, which is specifically prohibited by Article II of the OST. Therefore, Section 11 of the Artemis Accords, as currently written, violates the Outer Space Treaty. The pronouncements in Section 11, and throughout the Accords, that they are intended to comply with the Outer Space Treaty are not enough to negate the exclusionary nature of the “safety” zones.

Fortunately, the solution is simple. The parties to the Artemis Accords need only add the following sentence to the Accords, perhaps as a new sub-paragraph between Section 11 paragraph 7(c) and 7(d): “Access to resources shall be shared; any activity within the zones shall be conducted in such a manner that other parties can safely access any resource located there.” This is a restatement of Moon Treaty Article 9:

A State Party establishing a station shall use only that area which is required for the needs of the station… Stations shall be installed in such a manner that they do not impede the free access to all areas of the moon of personnel, vehicles and equipment of other States Parties conducting activities on the moon. [5a]

Sharing access to resources mitigates the exclusive nature of the zones; there would be no violation of the Article II prohibition against appropriation. Indeed, if the above provision is adopted, then much of the language in the Accords that mitigates the effect of exclusionary zones becomes superfluous.

We have already reached the point when sharing information about future activities can help avoid conflict. Every public and private entity that is interested in utilizing or developing an outer space resource should declare its intentions as soon as possible to promote cooperation and facilitate sharing access to resources.

The subtractable/rivalrous nature of outer space resources

Sharing access to resources addresses one of the issues presented by the de jure common-pool resource of outer space that is created by Article II of the Outer Space Treaty. But there is another issue that must be addressed, the other side of the coin of any common-pool resource: the finite, limited nature of space resources.

Although the OST prohibits exclusion, it does not prohibit the acquisition and/or use of outer space resources. If outer space resources were infinite, this would not be a problem. Outer space would be considered a non-exclusive, non-subtractable public resource, a true public commons. But there are practical limits to the amount of space resources that can be accessed, primarily due to limits in current Earth technology for reaching and utilizing them. Although outer space is de jure non-excludable, it is nevertheless de facto subtractable, and thus a common-pool resource with the potential for conflict.

Examples of subtractable resources on the Moon include water ice in the craters of eternal darkness at the poles, along with the peaks of eternal sunlight where solar energy can be harvested. Note that the sunlight itself is not a subtractable resource; it is the land and its location that is. Land has been considered a resource ever since the development of classical economic theory: it is tangible, its boundaries can be determined, and its value can be defined by its usefulness (i.e., the more useful the land at a given location, the more valuable it is as a resource).

There are different models for managing subtractable resources. The Artemis Accords rely on an exclusionary first-come, first -erved private property model. But as explained above, that model is prohibited by the Outer Space Treaty. It thus becomes necessary to create a new model, a new set of norms/agreements, that will provide the minimum legal structure necessary to support outer space activity.

The Space Treaty Institute has been working on such a legal framework since 2017. After much drafting, consultation, and revision, it has produced a Model Implementation Agreement for resource utilization/management under Article 11 of the Moon Treaty that satisfies the requirements of Article II of the OST. It is based on three organizational guidelines:

- The Agreement must support all public and private activity;

- It must protect essential public policies;

- It must integrate and build upon current institutions and processes.

The Model Implementation Agreement includes seven basic principles and processes:

- Share access to resources, including materials and land/locations;

- Share information, including the discovery of resources;

- Register activities;

- Develop standards, recommended practices, and interoperability;

- Protect the natural environment and scientific/historical sites;

- Establish dispute resolution, including consultation, arbitration, and mediation;

- Honor rights of individuals and settlements.

The proposed Model Agreement is not meant to address all conceivable issues, only those that are required at this time to protect essential public policies while providing the legal support necessary for sustainable public and private activity. The Moon Treaty itself calls for the review and possible revision of any implementation agreement every ten years as part of adaptive governance.

The full ten-paragraph Model Implementation Agreement can be found at www.spacetreaty.org.

The need for an international framework of laws to manage space resource activity

Why is this proposal necessary? As of late 2021, there is no internationally recognized mechanism for managing the utilization of space resources, including the land used for public or private activity. The current controlling international law is the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which prohibits any one country or its nationals from appropriation in Article II.

| The hopes and dreams of individuals and groups to create new societies in outer space are just as important as the entrepreneurship of those seeking to engage in space commerce. Both must be recognized, honored, and nurtured if humanity is to leave our home planet in a sustainable manner. |

Many countries agree that the prohibition against appropriation prevents any one country from granting exclusive property rights. But, as noted above, some disagree, enough to create the potential for conflict and uncertainty for businesses and investors. Since the function of law includes avoiding conflicts and reducing uncertainties, it is imperative to create an international legal framework now for resource utilization activity in outer space.

The Moon Treaty provides the international authority to manage resource utilization. Article 11 does not prohibit resource utilization; it just prohibits any one country or group of countries from imposing their exclusive regime on others:

11.1. The moon and its natural resources are the common heritage of mankind, which finds its expression in the provisions of this Agreement, in particular in paragraph 5 of this article.

11.2. The moon is not subject to national appropriation by any claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

11.3. Neither the surface nor the subsurface of the moon, nor any part thereof or natural resources in place, shall become property of any State, international intergovernmental or non-governmental organization, national organization or non-governmental entity or of any natural person. The placement of personnel, space vehicles, equipment, facilities, stations and installations on or below the surface of the moon, including structures connected with its surface or subsurface, shall not create a right of ownership over the surface or the subsurface of the moon or any areas thereof. The foregoing provisions are without prejudice to the international regime referred to in paragraph 5 of this article…

11.5. States Parties to this Agreement hereby undertake to establish an international regime, including appropriate procedures, to govern the exploitation of the natural resources of the moon as such exploitation is about to become feasible. [emphasis added] [5]

Note that Article 11 begins by stating that the “common heritage of mankind” is defined by the Moon Treaty and its implementation agreement. The CHM has no legal meaning or force of law beyond the framework that the States Parties adopt. Concerns that the CHM will result in a loss of sovereignty are misplaced and should not deter interested parties from considering the benefits of the Moon Treaty. The purpose and intent of Article 11 is to authorize the States Parties to create an international legal framework for managing resource utilization, so long as they do it together.

Limited central authority

Some fear that the Moon Treaty will create an overriding central entity. But polycentric governance of complex systems means that there is no need to establish a new governing body or agency. Limited authority, with specific principles and processes, is vested in treaties, and the States Parties mutually enforce the requirements using dispute resolution mechanisms.

A prime example of how this works today is the Svalbard Treaty (1925), regarding an archipelago near the Arctic Circle. Although it is nominally under the jurisdiction of Norway, any country that signs the Treaty can access any of the resources there, so long as they abide by certain principles such as non-military activity and protecting the environment. Current States Parties include Russia, China, the United States, and 43 others. The Treaty is administered by Norway, which provides the limited central authority.[7] But in outer space such authority can be provided by a treaty, such as the Moon Treaty with the Model Implementation Agreement, and mutually enforced by the member states.

Most of the Model Implementation Agreement deals with the utilization of resources and has been explained above. But a few more topics merit further explanation.

Developing standards and practices

The Model Implementation Agreement requires the States Parties to develop standards and recommended practices (SARP’s)—sometimes called “best practices”—for the development of outer space resources (Paragraph 6.) It does not create a super-agency that will override efforts that have been developing organically, though it does mandate that “standards or practices shall not require technology that is subject to export controls.” Rather, it requires the States Parties work with NGE’s, providing them a seat at the table and the legal support needed for their work. The International Organization for Standards (ISO)[8], the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR)[9], the Hague Group[6], the Moon Village Association[10], For All Moonkind[11], and the Space Treaty Institute[12] are examples of such organizations.

The Treaty anticipates that there will be ongoing advances in technology that will require a constant updating of standards and practices. It is essential for the States Parties to integrate the work of NGE’s into this process. Otherwise, a vast pool of talent and innumerable hours of work will be wasted. Without them, any governance of the common-pool resource will lack widespread organizational support and will likely fail.

Protecting historical and scientific sites

Article 7.3 of the Moon Treaty authorizes the preservation of sites of scientific interest:

States Parties shall report to other States Parties and to the Secretary-General concerning areas of the moon having special scientific interest in order that, without prejudice to the rights of other States Parties, consideration may be given to the designation of such areas as international scientific preserves for which special protective arrangements are to be agreed upon in consultation with the competent bodies of the United Nations. [5]

The Model Implementation Agreement clarifies that “special scientific interest” includes historical and cultural sites (Paragraph 7.) It is unclear whether a new organization/process will need to be established to meet these goals or if the task will be given to an existing organization (“competent body”) such as UNESCO. Until such decisions are made and procedures in place, the Model Implementation Agreement protects sites that are more than 20 years old.

Resolution of disputes

One of the best ways to provide minimal overall management of space resource activities is to let the interested parties sort out their differences themselves. Doing so requires establishing a process for resolving disputes.

Article 15 of the Moon Treaty describes levels of dispute resolution, beginning with consultations between the States Parties. Any other State Party can join in the consultations, and any State Party can request the assistance of the Secretary-General of the United Nations. If consultations fail to resolve the dispute, the States Parties are instructed to “take all measures to settle the dispute by other peaceful means of their choice appropriate to the circumstances and the nature of the dispute.” (Art. 15.3)

The Model Implementation Agreement also allows parties to voluntarily choose binding arbitration under the Permanent Court of Arbitration.[13] It also authorizes enforcement of any decision/award under a widely accepted convention. (Paragraph 9)

Non-binding mediation is also available, now that there is a separate international convention for enforcing any resulting agreements.[14] The decisions and agreements reached during any dispute resolution will help form the customary international law that will guide future activity.

Individual rights

What if an inhabitant of a settlement seeks asylum in another country’s facility? The Moon Treaty and the Outer Space Treaty contain certain provisions that suggest that their country of origin retains jurisdiction and can have them returned.

| The mission of space law must be nothing less than to restore that hope, to inspire humanity by giving the people of our planet a future they can believe in. |

Such control would conflict with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”), which states in Article 14.1 that “Everyone has the right to seek and enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.” [15] The Model Implementation Agreement incorporates the protections of the UDHR (Paragraph 10.) As explained above, this would override national laws and allow individuals to remove themselves from the legal authority of one country and enter the authority of another.

Settlements

Including the land used for settlements in the definition of “resources” is essential for creating an international framework of laws that is sufficiently comprehensive to support all private activity in space. It is the only way to override the prohibitions against appropriation in both the Outer Space Treaty and the Moon Treaty (see above.) This is done by interpreting “the exploitation of the natural resources of the moon” in Article 11.5 to include the use of any land/location on the Moon for any purpose.

When the Moon Treaty was first proposed, some individuals and NGEs, led by the L5 Society (now merged with the National Space Society), opposed it because there were no provisions for establishing private settlements with their own governance.[16] They pointed again to Articles 11.2, which states that “the moon is not subject to national appropriation by any claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means,” and 11.3’s prohibition against ownership. But as explained above, the international framework of laws authorized by Article 11.5 overrides those prohibitions. The proposed Model Implementation Agreement confirms that a settlement can seek autonomy and/or independence through customary international law (Paragraph 10.) In doing so, it promotes the principles of polycentrism and subsidiarity (governance as local as possible) while discouraging tendencies such as colonialism and over-control by a centralized authority. Some governance is essential, but the government that governs least governs best.

The hopes and dreams of individuals and groups to create new societies in outer space are just as important as the entrepreneurship of those seeking to engage in space commerce. Both must be recognized, honored, and nurtured if humanity is to leave our home planet in a sustainable manner. The Model Implementation Agreement states that “Nothing in this Agreement or in the Treaty shall be interpreted as limiting the rights of individuals under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights or the formation of sovereign states by settlements under customary international law.” (Paragraph 10) Any international framework of laws must acknowledge and incorporate these protections, or it will fail.

The historical perspective

The early 21st century is an extraordinary time. Humanity has been presented with an historic opportunity as it prepares to leave its home planet. Like those who went forward during the Age of Exploration five centuries ago, the decisions we make today will affect humanity for centuries, perhaps millennia. If ever there has been a time to determine how to implement humanity’s collective vision for the future, it is now.

In October 1957, people all over the world stood outside their homes as the sun set, looking to the sky as a blinking light passed overhead, the tumbling upper stage booster of the world’s first satellite, Sputnik. Because of the Cold War there was some fear, but for most the overwhelming emotions were excitement, inspiration, and hope. Despite all its imperfections, all its follies, and all its deadly conflicts, humanity had managed to throw off the shackles of gravity and reach the stars. All the stuff of science fiction suddenly seemed possible. And not just the stuff about technology; the writers, the poets, those who dared to dream of a better future saw a day when humanity could resolve its differences by peaceful means and move forward together.

This dream was enhanced a decade later, in December 1968, when our view of the world literally changed. As Apollo 8 rounded the Moon, the astronauts on board were suddenly overwhelmed as humans saw the Earth rising above the lunar horizon for the first time. The picture taken at that moment showed our home planet, beautiful and fragile, hanging in the vastness of space. Humanity as a species began to realize that we are all one, living together on a small planet hurtling through the cosmos.[17]

But even though no borders were visible, war and suffering continue to wrack the home world. In the half-century since, people have begun to lose faith in their governments, their private institutions, even in humanity itself. Every day people wake up to news of the increasingly disastrous effects of climate change, racial and gender injustice, worsening economic inequality, and assaults on democracy. To that has now been added the threat of war in outer space. The people of Earth are beginning to despair, wondering if there is anything they can really believe in. They are losing hope, and the resulting cynicism is poisoning our politics, our relationships, even our thinking.

The mission of space law must be nothing less than to restore that hope, to inspire humanity by giving the people of our planet a future they can believe in. To counter the despair of war and violence and neglect. To build that shining city on a hill that will light the way for all.

The time to act

It has been more than 500 years since the world has had such an opportunity to start anew. At that time, European countries used their advanced technology to perpetuate military conquest and economic exploitation as they competed for resources, causing widespread misery and countless wars. And when the Industrial Revolution came along, governments placed profits ahead of people, resulting in economic and environmental catastrophe. By 2021, many people have stopped believing in their ability to control their own destiny, or humanity’s.

We can change that. We can avoid making the same mistakes. But doing so requires immediate action. There will be only one time when humanity leaves our home world, only one chance to create a new pattern that will lead each person, and all nations, to their best destiny.

It is time to share the Moon.

References

[1] E. Ostrom, Beyond Markets and States: Polycentric Governance of Complex Economic Systems. Nobel Prize Lecture, Dec. 8, 2009, 412-13. (grid copied verbatim). Full paper at American Economic Review, vol. 100, no. 3, 641-72 (June 2010).

[2] Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs, aka The Outer Space Treaty (1967).

[3] The Artemis Accords, NASA (2020).

[4] National Space Laws, United Nations Office of Outer Space Affairs (2021).

[5] Agreement Governing The Activities Of States On The Moon And Other Celestial Bodies, aka the Moon Treaty (July 11, 1984). See also The Hague International Space Resources Governance Working Group, Building Blocks for the Development of an International Framework on Space Resource Activities (2019). “8. Resource rights 8.1 The international framework should ensure that resource rights over raw mineral and volatile materials extracted from space resources, as well as products derived therefrom, can lawfully be acquired through domestic legislation, bilateral agreements and/or multilateral agreements. 8.2 The international framework should enable the mutual recognition between States of such resource rights. 8.3 The international framework should ensure that the utilization of space resources is carried out in accordance with the principle of non-appropriation under Article II OST.” [emphasis added]

[5(a)] “Article 8

1. States Parties may pursue their activities in the exploration and use of the moon anywhere on or below its surface, subject to the provisions of this Agreement.

2. For these purposes States Parties may, in particular:

(a) Land their space objects on the moon and launch them from the moon;

(b) Place their personnel, space vehicles, equipment, facilities, stations and installations anywhere on or below the surface of the moon. Personnel, space vehicles, equipment, facilities, stations and installations may move or be moved freely over or below the surface of the moon.

3. Activities of States Parties in accordance with paragraphs 1 and 2 of this article shall not interfere with the activities of other States Parties on the moon. Where such interference may occur, the States Parties concerned shall undertake consultations in accordance with article 15, paragraphs 2 and 3, of this Agreement.

“Article 9

1. States Parties may establish manned and unmanned stations on the moon. A State Party establishing a station shall use only that area which is required for the needs of the station and shall immediately inform the Secretary-General of the United Nations of the location and purposes of that station. Subsequently, at annual intervals that State shall likewise inform the Secretary-General whether the station continues in use and whether its purposes have changed.

2. Stations shall be installed in such a manner that they do not impede the free access to all areas of the moon of personnel, vehicles and equipment of other States Parties conducting activities on the moon in accordance with the provisions of this Agreement or of Article I of the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies.”

[emphasis added]

[6] See, e.g., European Space Policy Institute, Artemis Accords: What Implications for Europe? ESPI BRIEFS No. 46, (Nov. 2020)

[7] Wikipedia, Svalbard Treaty. (Many thanks to Alex Gilbert, whose presentation on the Svalbard Treaty in February 2021 at the Commons in Space Conference provided the basis for this analysis. His work on outer space resources is also available here and here)

[8] International Organization for Standards (ISO).

[9] The Committee on Space Research (COSPAR).

[10] The Moon Village Association.

[11] For All Moonkind.

The Battle For Boca Chica

SpaceX is continuing preparations for orbital launches of its Starship/Super Heavy vehicle at Boca Chica, Texas, also called “Starbase”, as the FAA continues its environmental review. (credit: SpaceX) |

The battle for Boca Chica

by Jeff Foust

Monday, October 25, 2021

Few companies in the space industry are as polarizing as SpaceX, and few projects are as polarizing as its Starship vehicle. To advocates, it is humanity’s best hope to become a multiplanetary species, to use the phase frequently invoked by both the company and its supporters. To others, Starship is a high-risk venture, not just for the company and the space industry but also to the people and environment in the corner of Texas where it is being built.

| “I will always be on their side,” one commenter said of SpaceX. “I think their endeavors are absolutely necessary and vital to humanity as a species.” |

It took several tries, but SpaceX demonstrated that Starship could take off, fly a low-altitude test flight, land, and remain intact afterwards (see “Build back better,” The Space Review, May 17, 2021.) The next step is to demonstrate that Starship, launched by a booster called Super Heavy, can reach orbit, reenter, and touch down.

To do that, though, SpaceX needs a new FAA launch license. That, in turn, requires an environmental review of the company’s plans to determine the various effects it will have on the environment and whether, and how, they can be mitigated. An earlier environmental assessment, done back when SpaceX proposed using Boca Chica for Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launches, no longer applies to the far larger Starship/Super Heavy.

In September, the FAA released a draft programmatic environmental assessment (PEA) of SpaceX’s Starship/Super Heavy launch plans. The report itself does not determine if the FAA should license Starship orbital launches but instead assesses the environmental effects of launch activities and whether and how they can be mitigated. The report could lead the FAA to seek what it calls a “more intensive” environmental impact statement.

That report appeared to find little in the way of major obstacles to SpaceX’s plans. Many of the factors included in the assessment, from air and water quality to noise and visual effects, can be mitigated through measures outlined in the report. It did note, though, that it would not make a final decision until the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service performed a determination of potential adverse effects on endangered species in the area.

The release of the draft PEA kicked off a public comment period originally scheduled to run until October 18, but extended by the FAA to November 1. While comments can be submitted by email or postal mail, members of the public could also submit comments orally at public hearings, after FAA officials gave an overview of the project.

The pandemic has changed how those public meetings are run. Traditionally they are in-person events, where people line up to make their comments. The FAA, though, conducted these public hearings virtually, via Zoom, allowing people to tune in from home—wherever that may be—and provide their comments on the draft report.

That created interesting dynamics for the two public hearings held last week, running a combined nearly eight hours. While a traditional approach would have attracted primarily only local residents, people both watching and commenting online came from around the country, and in some cases outside the US.

That created two sharply distinct schools of thought about Starship. On one side were supporters of SpaceX who pressed the FAA to move full speed ahead on approving the environmental review as it currently stands and give SpaceX a license for Starship orbital launches from Boca Chica.

Those supporters hailed from around the country and beyond. “I’m totally on the side of SpaceX with this one,” said Brandon McHugh at the first public meeting October 18. “I will always be on their side. I think their endeavors are absolutely necessary and vital to humanity as a species.” He called on the FAA to allow SpaceX “to proceed as much as they need to.”

| “The stakes are simply too high not to invest in a thorough EIS,” said Wilcox. |

He was hardly the only one with similar views. “I stand with SpaceX and want them to have full approval to do as many launches as they need to make this system actually work,” said Aiden Girlya at the second meeting October 20. “I do not believe they should be limited to a certain amount. They should be able to do as many launches as they need to because we have not seen any environmental impacts so far.”

The majority of those supporters lived far from Brownsville, but some lived in and around the area. The last speaker at the first public meeting was Jessica Tetreau-Kalifa, a Brownsville, Texas, city commissioner. She argued that SpaceX had turned the city from one of the poorest in the country to “one of the most sought-after ZIP codes” to live and work. “I don’t just ask you, I beg you to give them that permit,” she told the FAA.

Those supporters often pointed to Cape Canaveral as an example of how a launch site could co-exist with the environment, with launch sites embedded with the Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge. “Space launch facilities so far seem like they’re good, not bad, for the environment,” said Luc Fueston. “You can pan over on Google Maps to Florida to see the impact over there. It just looks like a sea of green.”

Many local residents, and environmentalists, disagreed. SpaceX’s current activities have already had impacts, they argued. Bill Berg, a member of a nonprofit group called Save RGV that is opposed to the site, noted at the October 20 hearing that the number of nests of piping plovers, a threatened bird species, had dropped in the area from 41 three years ago to one this year.

Sharon Almaguer, who lives in Port Isabel, a town north of Boca Chica, complained that SpaceX activities had shut down access to Boca Chica Beach far more often than allowed under existing agreements. (The Texas state constitution, she and others noted, guarantees open access to beaches.) Past Starship tests created excessive noise as well. “My house shakes with little rockets,” she said, a reference to the series of Starship suborbital tests. Orbital flights, she predicted, will lead to “widespread property damage.”

Many opponents also questioned aspects of the draft PEA, including its treatment of a proposed 250-megawatt power plant as well as transportation and handling of methane fuel for the vehicles. “This is a large oil and gas operation,” said Eric Hound, who has written extensive essays criticizing the environmental review.

Those issue were enough for them to call on the FAA to develop an environmental impact statement, a more rigorous report that will take many months to complete. “The stakes are simply too high not to invest in a thorough EIS,” said Sharon Wilcox, senior Texas representative for Defenders of Wildlife, a wildlife conservation nonprofit, at the October 18 meeting.

The rhetoric on both sides got heated at times. Rebekah Hinojosa, a resident who spoke at both meetings, claimed the FAA was violating the Civil Rights Act by not providing material in Spanish and providing only short notice that translation would be available. “SpaceX is just something that is directly destructive and another example of colonization of our community that we just don’t need,” she said.

Another speaker suggested that locals just deal with it. “The outspoken opponents of SpaceX in Cameron County are rightfully expressing their displeasure with the annoyance of having such a game-changing operation in their backyard. But to make an omelet, we must first break eggs, right?” said Dan Holmes, who called in from Nome, Alaska, thousands of kilometers from both the omelet and the cracked eggshells.

While someone monitoring the hearing tried to keep track of the number of comments for and against SpaceX’s plans, the public comment period is not a vote. FAA will review the comments and use them to evaluate any changes needed to the draft report, and also consider whether an EIS is necessary. That decision could take months.

| “We follow the NEPA rules, but it is the longest pole in the tent when it comes to licensing,” Monteith said. |

Boca Chica is not the only commercial launch site embroiled in environmental controversy. The proposed Spaceport Camden in Camden County, Georgia, has faced opposition from local residents and environmental groups for years regarding the risks posed by launch failures there. That has caused the FAA to push back a decision on the spaceport’s license for months as it continues to work with stakeholders. That decision is now expected by November 3—unless the date slips again.

“Protecting the environment is critically important,” said Wayne Monteith, FAA associate administrator for commercial space transportation, during a panel session at the American Astronautical Society’s Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium earlier in the month in Huntsville, Alabama.

“However, I think there’s got to be a balance,” he added. That desire for balance comes from concerns that companies may be forced to look outside the US for launch sites. “I don’t think the Department of Defense or NASA want to launch from another country on a regular basis.”

He said that, unlike recent efforts to streamline overall launch licensing regulations, there is little he can do to revise environmental reviews, which are governed by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). “We follow the NEPA rules, but it is the longest pole in the tent when it comes to licensing,” he said. The environmental review work can take up five years.

“We’ve got to work through it,” he concluded. “Otherwise, we run the risk of significantly impacting the ability of this industry to move forward and continue to lead the world.”

Finding balance between environmental and industry needs is hardly a new challenge overall. But striking that balance is easier said than done when public views—at least among those willing to speak in online public hearings—are so sharply divided.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Venus-Toxic Neighbor

Toxic Neighbor

Previous studies have suggested that the Earth’s sister planet, Venus, was once able to support life. But, recent findings have uncovered evidence that it was always a scalding and toxic planet, according to Science Alert.

A new study looked into the climate models of Venus and Earth in their early years to determine when – and whether – the former could sustain life.

The authors explained that water would have been present in the form of steam on both planets’ surfaces while they were cooling down more than four billion years ago.

The steam would eventually condense into clouds and produce rain. This could only happen, however, if clouds were to form to block solar radiation from the surface of Venus.

But the climate models suggested that on Venus, clouds could have been present only on the planet’s cooler night side. Meanwhile, Venus’ dayside was getting cooked by solar radiation, which also generated a powerful greenhouse effect on the night side.

As a result, vapor couldn’t condense, and – if it did – it wouldn’t have produced enough rain to fill up Venusian oceans.

The research team is still unclear how Earth and Venus ended up on different evolutionary paths but hopes that further research and future space probes to the planet might yield answers.

It isn’t possible to figure this out on our computers, says co-author David Ehrenreich: “The observations of the three future Venusian space missions will be essential to confirm – or refute – our work.”

Tuesday, October 26, 2021

Friday, October 22, 2021

Thursday, October 21, 2021

Friday, October 15, 2021

Thursday, October 14, 2021

Wednesday, October 13, 2021

Captain James T, Kirk Made It To Space!!!!

The night of

September 8, 1966, was hot, sultry, and humid in Houston. My sister and I were

in our home at 5715 Belarbor Avenue. We were in her room and watching a

portable television. At 8:00 in the evening on channel two (NBC) a new series

called Star Trek premiered. Its star was a 37-year-old actor from Montreal,

Canada named William Shatner. He was not a big name. He had worked regularly in

television.

The series premiere was mesmerizing. It was

about a shape-shifting alien who could take on the appearance of anyone to lure

humans to come close. The alien would attach itself to the human and suck out

all the salt in the victim's body. Death of the victim would follow. Little did

we know that a revolution was starting. It is still with us 55 years later.

William Shatner is still with us. He is

"90-years young." At 7:00 AM Pacific time, he will lift off in a Blue

Origin Shephard rocket for a 15-minute suborbital flight. He will truly

"go where few men and women have gone before." Captain Kirk,

Godspeed!!

Monday, October 11, 2021

The UK Looks For Its Place In Space

The UK looks for its place in space

by Jeff Foust

Monday, October 11, 2021

It was a line that launched a thousand jokes. When the British government released a national space strategy document September 27, it included a foreword from Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who decided to riff off the concept the government had been pushing of a “Global Britain” in the post-Brexit era.

The report, Johnson wrote, offered “a plan that will see us take a leading role on the international stage, Global Britain becoming Galactic Britain as we work with other nations to pursue exciting missions and with the UN to set the standards that will ensure space is used responsibly and safely.”

| “At the heart of this strategy, we recognize and state clearly that we see this as part of a global race for the new space economy, and the UK has some very strong strengths that we want to play to,” said Freeman. |

The idea of a “Galactic Britain,” whatever that meant, drew guffaws as the country struggled to find its bearings in the aftermath of both the coronavirus pandemic and Brexit. At least, more than one person pointed out, in a Galactic Britain the suns would never set on the British Empire.

The comments about Galactic Britain distracted from the substance of the report, which was an effort by the government to outline exactly what role it saw Britain playing in a growing global space economy, particularly now that it was no longer part of the European Union but still a member of the European Space Agency.

“At the heart of this strategy, we recognize and state clearly that we see this as part of a global race for the new space economy, and the UK has some very strong strengths that we want to play to,” said George Freeman, who was appointed science minister in the British government last month, during a presentation at the UK Space Conference the day of the report’s release.

The report was a mix of goals, pillars, and ten-point plans for Britain’s future in space. The report listed five goals for the UK in space: growing its space economy, promoting an “open and stable international order” in space, supporting space science research and inspiring the public, protecting national interests in and using space, and using space to support both British citizens and the world.

The UK would achieve those goals through four pillars. One is to grow the country’s space sector in several ways, such as promoting development of launch vehicles and spaceports, implementing “modern” space regulations, and ensuring access to financing and insurance. A second pillar is devoted to international collaboration, primarily through ESA but also directly with other countries, including the United States. A third pillar seeks to turn Britain into a “superpower” in space science and technology through participation on ESA programs and increased defense investment in space. The fourth and final pillar involves development of “resilient” space capabilities, from communications and navigation to launch and satellite servicing.

That’s a lot, something the government acknowledged in the report. “Government cannot pursue every space-related activity now. We must make tough strategic choices and target resources to pursue the highest impact opportunities and the critical cross-cutting enablers that will lay the groundwork for a thriving future in space,” it stated (emphasis in original.)

That prioritization took the form of a ten-point plan identifying initial focus areas. Those range from becoming the “leading provider of commercial small satellite launch in Europe by 2030” and “establish global leadership in space sustainability” to using space services to modernize the country’s transportation system.

The ambition of the report, at the very least, won over many in the British space industry. “Moving space up the priority list within government through the new National Space Strategy is most welcome and can help to unleash the UK sector to drive further green economic growth and make significant contributions to the levelling up agenda,” said Rajeev Suri, CEO of London-based satellite operator Inmarsat.

“The first UK National Space Strategy highlights the potential of the end-to-end space capabilities provided by the UK space industry,” said Edward F. Jamieson, business development manager for government programs for NanoAvionics UK, a smallsat manufacturer. “The importance of small satellite technology, in furthering the development of the UK space industry as recognized in the Strategy, should not be underestimated.”

But, while the strategy was long on ambition, it was short on details. The goals were all very qualitative, and even the specifics of the ten-point plan offered few concrete metrics other than conducting the “first small satellite launch from Europe in 2022” and bring the leading provider of smallsat launch in Europe by 2030.

In fact, the report dropped one quantitative metric the British government had been using for the industry. For the last several years, the government had set the goal of capturing 10% of the global space economy by 2030. In 2019, the British space sector generated £16.4 billion out of a global space economy it estimated at £270 billion, or about 6%. But the strategy document, while mentioning the size of the British space sector, made no mention of a 10% goal.

| The report noted that the UK space sector has grown at an annual rate of 4.7% in the last four years. But it also stated that the global space economy was forecast to grow at an annual rate of 5.6% through 2030. |

That omission was deliberate, a government official said during a panel later in the online conference. “It’s been quite a long time since that initial 10% target was set,” said Rebecca Evernden, director for space at the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

“We concluded that we needed a more sophisticated way to measure growth in the various parts of the UK space sector which is less clumsy, if you like, than a single headline growth target which is somewhat subject to the whims of foreign exchange rates and other factors that can perhaps skew the big picture of what is a very strong growth story in the UK,” she said. The government is working on an alternative set of metrics, but she offered no specifics on what those would be or when they would be ready.

Another reason for abandoning the 10% goal, perhaps, is that the UK was not gaining ground on it. The report noted that the UK space sector has grown at an annual rate of 4.7% in the last four years. But a technical annex to the report stated that the global space economy was forecast to grow at an annual rate of 5.6% through 2030. It’s hard to gain market share when your national space economy isn’t growing as fast as the global space economy.

Another detail missing in the report was funding. The strategy document doesn’t commit the government to any new funding to support civil, military, or commercial space activities.

Freeman said at the conference that the lack of information on funding was because a national budget, called the Comprehensive Spending Review, was due out in October and would include those details. “Let me reassure you,” he said, “we wouldn’t be launching this strategy now if we weren’t fully committed to it.”

Another uncertainty is the UK’s relationship with the EU post-Brexit. When the two governments reached a final agreement late last year on Britain’s exit from the EU, they agreed that the UK would no longer have access to the secure signals from the Galileo satellite navigation system—it could continue to use the public signal, like the rest of the world—and British companies would no longer be able to work on the program.

With Brexit looming, the British government suggested it would pursue some kind of satellite navigation system of its own. That interest, many in the industry believe, led to the government joining forces with Indian telecom company Bharti Global to acquire OneWeb after it filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection last year. OneWeb executives say they are interested in offering navigation services, although that may have to wait until a second-generation constellation. The strategy only says that the government “is evaluating the case for investing in resilient Position, Navigation and Timing (PNT) capabilities through a mix of innovative new terrestrial and space-based technologies.”

| “We’re already behind the rest of the world,” said Stanniland. “If we don’t outpace them, we’ll never catch up.” |

The situation with the EU’s other major space program, the Copernicus series of Earth observation satellites, is more complex. Under last year’s Brexit agreement, the UK can continue to be a part of Copernicus, but an agreement needed to implement that cooperation hasn’t been finalized. Copernicus is also a joint program between the EU and ESA, with UK a major player in the ESA aspect of the effort.

Copernicus “is a vital part of our ecosystem,” Freeman said, but didn’t elaborate on the status of that implementing agreement with the EU.

“The UK might have left the European political union, but we’re not leaving the European scientific, cultural and research community,” he said, noting that he had backed Remain in the 2016 Brexit referendum. “We want to make sure that, post our withdrawal from the EU, we become an even stronger player in that research community.”

While many in industry welcomed the new strategy, at least one executive on a conference expressed a sense of urgency for the UK to place a greater emphasis on space as it finds its place in Europe and the world.

“We’re already behind the rest of the world,” said Andrew Stanniland, CEO of Thales Alenia Space UK. “If we don’t outpace them, we’ll never catch up.”

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

The Russian Movie - "The Challenge"

Among The Stars

Space, the final frontier, has had its shares of visitors over the past decades, from animals to billionaires.

Recently, a Russian movie star and director became the latest individuals to visit space – but the first to shoot a movie around the Earth’s orbit, CNET reported.

The Soyuz spacecraft carrying actor Yulia Peresild and director Klim Shipenko along with veteran cosmonaut, Anton Shkaplerov, successfully docked at the International Space Station last week following a short flight from Earth.

The two artists will be filming a Russian film called “the Challenge” during their 12-day stay. The movie is about a surgeon – played by Peresild – sent to the space station to treat a cosmonaut – played by another veteran cosmonaut Oleg Novitsky – after he suffered a heart attack during a spacewalk, according to Space.com.

Both Peresild and Shipenko had to undergo months of training to ensure a successful mission, which they described as “psychologically, physically and morally hard.”

Even so, the fact they visited space still astounds them.

“I still feel that it’s all a dream and I’m still asleep,” Peresild, an award-winning actor, told Russia’s Channel One.

The Russian film crew became the first to shoot a feature film in space, beating actor Tom Cruise: Last year, Cruise and director Doug Liman announced they were working with NASA on a movie to be filmed in space, according to CNN.

One day, space epics such as Star Wars and Star Trek might be filmed on location.

Sunday, October 10, 2021

Friday, October 8, 2021

Wednesday, October 6, 2021

Review Of The Television Series Countdown-We Are All Going To Space

Review: Countdownby Jeff Foust |

| There is dramatic aerial footage of the launch—shot, presumably, from a drone near the pad—looking down as the Falcon 9 lifts off, turning dusk briefly back to day, and following it until the rocket soars past towards space. |

Inspiration4, the private orbital crewed spaceflight on a SpaceX Crew Dragon last month, had its own approach to media. There were a few media briefings between the time the mission was announced in February and the launch in September, although some reporters complained they couldn’t get access to the phone line for the final briefing the day before launch. However, the project invested more in special arrangements with specific outlets. Shortly after the announcement of Inspiration4, Time revealed it had secured the “competitive documentary rights” to the mission, giving it “exclusive access to the groundbreaking mission.”

While Time featured Inspiration4 in a cover story in August, the culmination of that effort was Countdown: Inspiration4 Mission to Space, a documentary series available on Netflix. The five-part series follows the mission from Jared Isaacman’s announcement of the mission and select of the three people who fly with him through training. The final episode, released last week, covers the mission itself, from final preparations for launch through splashdown.

The first two episodes are really introductions to the mission and the crew. The first covers Isaacman, the billionaire backer and commander of the mission, as well as Hayley Arceneaux, the St. Jude physician assistant and pediatric cancer survivor picked to fly, not to mention background on the mission itself. The second covers the other two participants, Sian Proctor and Christopher Sembroski, selected through contests. The third and fourth episodes go through various training for the crew, from centrifuges and high-performance jets to a climb of Mt. Rainier.

The payoff comes in the final episode, released last week (the first four were released in early September.) This episode starts in the final days before launch, when the crew arrives at the Kennedy Space Center for their final preparations and launch rehearsals—and goodbyes to loved ones—and then launch itself. Then we get to see the four in orbit, with much more footage than was available in realtime during the three-day mission. It concludes with the splashdown and the crew reuniting with their families, wrapping up a successful mission that has changed their lives and took a step forward for commercial spaceflight.

| While the footage, and the interviews, were fascinating, the documentary seems to lack something: drama. |

The filmmakers took advantage of their exclusive access to take viewers behind the scenes of the mission. There are extensive interviews with the four crewmembers, their families, and others working on the mission, including SpaceX employees (Elon Musk makes brief appearances in the show, but isn’t a central figure.) There is dramatic aerial footage of the launch—shot, presumably, from a drone near the pad—looking down as the Falcon 9 lifts off, turning dusk briefly back to day, and following it until the rocket soars past towards space. There’s also video of the crew in space, having fun in weightlessness and enjoying the views of Earth from the spacecraft’s cupola, far more than the glimpses we got during the mission.

While the footage, and the interviews, were fascinating, the documentary seems to lack something: drama. Yes, there’s the thrill of the launch and landing, but by the time viewers saw the final episode the mission the crew had been safely back for a week and a half. Rarely over the course of training and the flight itself do you see the crew dealing with setbacks or problems, or even disagreements among themselves.

And we know that, while the mission was highly successful, it wasn’t perfect. During a post-splashdown call, SpaceX and Inspiration4 officials acknowledged a minor problem with the spacecraft’s toilet: not a mission-ending issue but something that the crew and ground controllers had to address. That doesn’t come up in the show, which instead shows the crew holding video conferences with their families and St. Jude patients, playing with their food in weightlessness, and looking out the window.

Similarly, in that media call, Inspiration4’s Todd Ericson suggested that at least some of the crew experienced spacesickness, saying that the crew was “tracking on target to NASA astronauts”; past studies have indicated half or more of NASA astronauts experience spacesickness to some degree in their first few days in space. But in none of the footage did anyone on Inspiration4 look sick, and the topic never came up.

The documentary also leaves unanswered other questions about the mission, like its origins. Isaacman said he was long interested in space and attended a 2008 Soyuz launch whose crew included private astronaut Richard Garriott. But in the documentary he’s vague about how the mission got started. He said he mentioned he was on a call last year with SpaceX “not related to me going to space or any human going to space” where he offhandedly mentions he would be interested in going to space. “Actually, we might be a lot more ready than you might think, and if you want you have the opportunity to be the first,” he said he recalls them saying. He never says what that unrelated discussion was about—he runs a payment processing company, so his professional overlap with SpaceX would be limited—or just how that comment turned into a contract. (A slide visible in a meeting shown later in the first episode shows that the contract was signed in November 2020, with a kickoff meeting in January, just before SpaceX and Inspiration4 publicly announced the mission.)

Countdown: Inspiration4 Mission to Space is, in some respects, something of a throwback to the early days of spaceflight. The Mercury 7 astronauts had an exclusive contract with Life magazine, giving the magazine special access to the astronauts and their families in exchange for glowing, and sanitized, coverage of them. That was an approach later discontinued by NASA after criticism from other publications. The difference is that, in this new era of private human spaceflight, companies are well within their rights to set up exclusive media deals and decide with whom they want to work. But there is a value in openness that goes beyond the monetary value of any exclusive arrangement, one that spaceflight companies would do well to consider in the future.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.