Since I was a young child Mars held a special fascination for me. It was so close and yet so faraway. I have never doubted that it once had advanced life and still has remnants of that life now. I am a dedicated member of the Mars Society,Norcal Mars Society National Space Society, Planetary Society, And the SETI Institute. I am a supporter of Explore Mars, Inc. I'm a great admirer of Elon Musk and SpaceX. I have a strong feeling that Space X will send a human to Mars first.

Wednesday, November 30, 2022

Tuesday, November 29, 2022

Monday, November 28, 2022

Sunday, November 27, 2022

Saturday, November 26, 2022

Friday, November 25, 2022

Book Review Art Of The Cosmos

|

Review: The Art of the Cosmos

by Jeff Foust

Monday, November 21, 2022

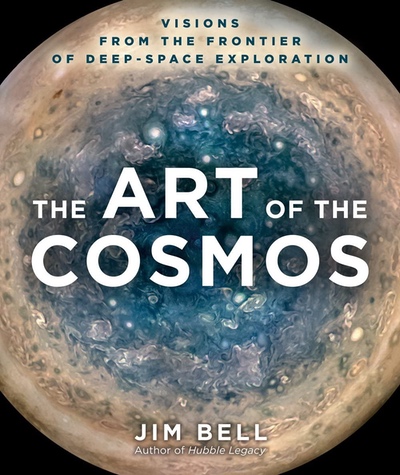

The Art of the Cosmos: Visions from the Frontier of Deep Space Exploration

by Jim Bell

Union Square & Co., 2022

hardcover, 224 pp., illus.

ISBN 9781-4549-4608-3

US$35.00

There’s no shortage of books published over the years that have illustrated the beauty of the universe. Often they’re large-format books with glossy pages and colorful images of galaxies, nebulae, planets, and moons, attracting the reader. The imagery is beautiful—like works of art—but they’re intended primarily to illustrate the science of the solar system or the universe.

In The Art of the Cosmos, planetary scientist Jim Bell embraces the artistic aspect of those images. “If one of the roles of art is to extend our senses and our experiences into the realm of the unknown and the unfamiliar, to imbue us with a sense of awe and wonder at the glory and grandeur of nature, and to push the boundaries of what we know and feel,” he writes in the book’s introduction, “then deep space exploration has provided some of the most spectacular and humbling kinds of art that humans have ever produced.”

| Bell believes that “deep space exploration has provided some of the most spectacular and humbling kinds of art that humans have ever produced.” |

In the book, he gathers more than 125 examples of such art, primarily photographs, that stand out as examples of cosmic art. They range from a sunset on Mars, tinged with shades of blue rather than orange and red, to a kilometer-high cliff on Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko that draws parallels to El Capitan in Yosemite, to the Flame Nebula, its dark red dust contrasting with the bluish glow of ionized hydrogen.

Bell selected images that he said hewed to many of the characteristics of terrestrial art, like composition, lighting, and perspective. Those elements may be accidents of planned observations by spacecraft or telescopes, but in some cases, like the Martian sunset, planned at least with the potential for aesthetics as well as science. Many of the images in the book are products of sophisticated hobbyists who take raw images from missions and combine and reprocess them to create stunning new images.

Despite the title, The Art of the Cosmos leans strongly towards art of the solar system: three of the four chapters are devoted to solar system bodies, with the rest of the universe crammed into the final chapter. Bell acknowledges that “bias” in the introduction, noting his background working on planetary missions (including Mars, which may be why that planet gets most of one chapter, sharing it only with asteroids and comets.) That last chapter relies heavily on Hubble images; an interesting choice given there’s a much larger astrophotography community, producing their own fantastic images, than those processing images from spacecraft. That’s not to say the Hubble images aren’t works of art, only that there may be an ever greater variety to consider as well.

The Art of the Cosmos is not a book about the science of the solar system and universe, although Bell does include scientific explanations for the images. It is more of a celebration of the beauty of the cosmos, and a reminder that art and science are not distinct but, rather, intertwined.

| “Stories of space adventurers riding rocket-propelled vehicles into the space frontier became so accepted that no one questioned the various elements of these tales or why those elements fit together.” |

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Thursday, November 24, 2022

Some Beautiful Words From A Russian Lady

Wednesday, November 23, 2022

Tuesday, November 22, 2022

Ift Off And Back To The Moon

Liftoff |

Humankind took one small step toward the moon yesterday: NASA’s uncrewed Orion spacecraft arrived at the dusty orb and dipped as close as 81 miles above the surface, part of a multiyear project to return to our closest celestial neighbor half a century after the last visit. |

After several delays, NASA’s Artemis program got underway with last week’s launch of Artemis I propelling Orion into the heavens. So far, it has not provided the same drama and romance of the original Apollo moon landings. But for the first time since the astronaut Gene Cernan climbed back into his lunar module as the last person on the moon on Dec. 14, 1972, there is a sustained commitment to going back. |

“Why the moon now?” asked my colleague Kenneth Chang, who covers the space program for The Times. “There’s a lot we still don’t know about the moon. Everyone sort of lost interest in the moon for 20 years after Apollo. The moon was like, ‘Oh, we’ve been there, done that, it’s just a rock, no atmosphere, it’s not that interesting.’ Scientifically, what changed is in the ’90s, people started thinking there might be water-ice on the moon. This was a major change in thinking.” |

If there is water on the moon, you can split off hydrogen from oxygen and make rocket fuel. Such a prospect would be transformative because the moon could be used as a base for deep-space missions without the cost and burden of lifting heavy rocket fuel off the Earth, which has six times the gravity of the moon. “Scientifically, that’s a cool possibility,” Ken told me, “and so people started getting interested in the moon again.” |

To my thinking, Ken has one of the coolest jobs in journalism. He and I spoke yesterday after the Orion flyby. |

Peter: Why are we going back to the moon now, and why haven’t we for 50 years? |

Ken: We’ve tried at least two times previously. Going back to the moon takes 10 years. Even though technology has gotten better, it’s not something we can do quickly. Every new administration wanted to have its own stamp on space policy, and it got cut. This is the first time the program hasn’t gotten cut in two administration changes. Donald Trump basically continued what was going on under Obama; he changed the initial destination from Mars back to the moon, but it’s still basically the same. And then President Biden hasn’t changed it from Trump, basically. |

Artemis I launched Wednesday and reached the moon this morning. This mission is meant to test this new generation of equipment. How is it going? |

There have been small glitches, like the star trackers on Orion got confused, so NASA figured out how to work around that. There are small things like that going on, but that’s why they’re flying. If everything went perfectly, they wouldn’t need to do the test. So far, 99 percent of it is going pretty much as they wanted to. |

The spacecraft is scheduled to return to Earth on Dec. 11. What else is ahead for this mission before then? |

NASA officials want Orion to be out in deep space for a set of time to make sure nothing weird happens from radiation. And the last big thing they want to test is the heat shield. They’re coming back at a really high velocity, and they want to verify that the heat shield survives re-entry. |

The next mission, Artemis II, set for 2024, will have a four-person crew fly to the moon but not land. If you’re going all that way, isn’t it frustrating not to touch down? |

Yeah, but you want to make sure the life support systems work properly. And secondly, under the plan, the lander won’t be ready by then. It’s really complicated, and you don’t want to risk lives unnecessarily. |

The Artemis III mission that will finally put humans again on the surface, including the first woman and first person of color, will be in, what, 2025, if everything goes perfectly? Or is that a stretch? |

That’s a huge stretch. Outside experts are saying 2028 would be the earliest. It’s very optimistic that they can get Artemis II off in 2024. |

You studied physics at Princeton and later got a master’s in physics, worked at a supercomputing center and were working on a doctorate but gave it up to go into journalism. Why? |

I wasn’t that good a physicist. During grad school, I spent one summer at a San Francisco Chronicle program where they had grad students work to improve communication between scientists and journalists, and I realized that was more fun than doing science. |

If you could be the first journalist to fly to the moon, would you want to? |

I used to. I wanted to become an astronaut, at least for a while. Then I saw “First Man,” the movie about Apollo 11 that showed what the mission was like. I remembered I’m afraid of heights and I’m claustrophobic, so those rockets may not be the best for me. |

Related: “I would give it a cautiously optimistic A+,” the Artemis mission manager said about the flight so far. |

Monday, November 21, 2022

Sunday, November 20, 2022

Saturday, November 19, 2022

Wednesday, November 16, 2022

SLS Blasts Off!!!!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Saturday, November 12, 2022

Thursday, November 3, 2022

Wednesday, November 2, 2022

Tuesday, November 1, 2022

Who Should Regulate New Commercial Space Activities

Companies developing new space services, like satellite life extension, are seeking certainty about which government agency or agencies will regulate them. (credit: Astroscale) |

The debate about who should regulate new commercial space activities

by Jeff Foust

Monday, October 31, 2022

A small step towards reducing the growth of debris in low Earth orbit could trigger a much bigger debate about who in the federal government regulates space activities.

| “I think the FCC, for their part, has pushed the boundaries of their authorities pretty aggressively,” said DalBello. |

On September 29, the Federal Communications Commission voted unanimously to adopt a draft order earlier this month to set new requirements for disposing of satellites at the end of the missions. The FCC order requires satellites that end their lives in orbits at altitudes of 2,000 kilometers or less to deorbit their satellites within five years. It replaces guidelines that called for deorbiting satellites within 25 years after their mission ends.

“Twenty-five years is a long time. There is no reason to wait that long anymore, especially in low Earth orbit,” said FCC chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel during brief comments at the FCC meeting.

There was no debate at the meeting against the proposed rule, intended to speed up the disposal of satellites in an era when increasing numbers are being launched for remote sensing and communications constellations. “With this order, we do take that practical step of reducing the demise times in LEO to no more than five years, a timeframe that is readily achievable,” said another commissioner, Geoffrey Starks. “Compliance will be the new rule here to bend the curve of debris proliferation.”

There was little debate about changing that deadline for post-mission disposal from 25 to 5 years. Most in the industry agreed that the 25-year guideline, crafted some two decades ago, was out of date given the rapidly growing population of satellites and debris in LEO. In comments to the FCC, companies primarily asked for exceptions for satellites that suffer anomalies or other malfunctions beyond their control. None expressed opposition to the proposed order.

While there was no opposition to changing the deorbit lifetime to five years, there was debate about whether the FCC is the right agency to do it. Two days before the FCC vote, the bipartisan leadership of the House Science Committee asked the commission to delay the vote, questioning its authority to regulate deorbit lifetimes.

In a letter, members said they supported efforts for a “safe, sustainable space environment” and did not object to the five-year post-mission disposal timeline itself. “However, we are concerned that the Commission’s proposal to promulgate rules on this matter could create uncertainty and potentially conflicting guidance.”

The members questioned whether the FCC had the authority under existing law to craft such regulations, an issue they raised two years earlier when the FCC was considering a similar change. The FCC then decided to delay consideration of the change to get more feedback, and not necessarily because of those legal concerns.

House members also worried about confusion that the FCC’s decision would make. A separate interagency effort, coordinated by the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), is working on related issues as part of an Orbital Debris Implementation Plan issued in July. One topic of that plan was to revisit the 25-year deorbit rule that is part of current government guidelines.

| “We have, through the option of extending our orbital debris rules to any who seek US market access, a regulatory hook for creating a default rulebook for commercial operators globally,” said Simington. |

Ezinne Uzo-Okoro, assistant director for space policy at OSTP, downplayed any conflict between that implementation plan and the FCC’s action. “The FCC is part of, and continues to be part of, the orbital debris interagency working group,” she said the day of the FCC vote at the Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance Technologies (AMOS) Conference in Hawaii. “It’s all working in tandem. It’s not a separate effort.”’

But another government official, speaking at the same conference the next day, offered a more critical assessment. “I think the FCC, for their part, has pushed the boundaries of their authorities pretty aggressively,” said Richard DalBello, director of the Office of Space Commerce, which is working to take over civil space traffic management responsibilities from the Defense Department as part of Space Policy Directive 3.

“Although I certainly congratulate them on the depth of their intellectual work,” he said of the FCC, “a lot of the things that they articulated are probably, arguably, outside their job jar.”

The FCC stepped up years ago with first applying the 25-year guideline to licenses, and now with the new five-year rule, in part because no one else in the federal government was interested, or felt they had the authority, to implement it. The new rule, which takes effect in two years, will apply not just to companies that apply for FCC licenses but also to satellites licensed in other nations that seek “market access,” or permission from the FCC to provide services in the United States, giving it a reach that goes beyond many government regulations.

“We have, through the option of extending our orbital debris rules to any who seek US market access, a regulatory hook for creating a default rulebook for commercial operators globally,” said Nathan Simington, an FCC commissioner. “That’s a powerful, even irresistible, incentive.”

The FCC’s orbital debris regulation comes amid a broader discussion about who should regulate new commercial space activities. The FCC, for example, licenses communications, while the Office of Space Commerce, currently within NOAA, licenses commercial remote sensing satellites. The FAA licenses commercial launches and reentries.

A long-running debate, though, has revolved among new space applications that don’t fit neatly within those existing markets: satellite servicing, commercial space stations, lunar landers, and more. The United States, to comply with Article VI of the Outer Space Treaty, has to provide “authorization and continuing supervision” of space activities carried out by companies and organizations.

There have been plenty of proposals for who should be responsible for “mission authorization” of those activities, typically focusing on the FAA or the Office of Space Commerce. At the Beyond Earth Symposium in Washington October 13, George Nield, former associate administrator for commercial space transportation at the FAA, proposed it should go to the FAA’s parent agency, the Department of Transportation.

“My recommendation is that we take this opportunity to recognize spaceflight as a mode of transportation, just like highways, railways, maritime, aviation, and pipelines, and create a Bureau of Commercial Space Transportation under the U.S. Department of Transportation,” he said. “That could be a one-stop shop for regulating space.”

| “I look at that and take that as a sign that this is my opportunity to tell the FCC that they are not a mission authorization body,” said Cummings of a recent FCC notice. |

Others advocate for Commerce. “You have a department that is used to working with industry,” said Joel Graham, partner at Meeks, Butera, & Israel and a former staff member on the Senate Commerce Committee, during a panel at the American Astronautical Society’s Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium last week. “I think Commerce is probably the most agile and makes the most sense for placing these highly dynamic activities.”

The Biden Administration, through the National Space Council, is working on its own proposals for mission authorization. At the September 9 meeting of the council, Vice President Kamala Harris directed agencies to provide proposals on mission authorization within 180 days (see “A substantive National Space Council meeting”, The Space Review, September 12, 2022).

As part of that effort, the council is planning two public “listening sessions” on November 14 and 21. The first will seek feedback on novel space capabilities and the second will be devoted to approaches for the authorization and supervision required by the Outer Space Treaty.

That effort got going in the last several months “because the vice president became very aware of some of the issues” after meeting with several companies that are doing novel commercial activities, said Diane Howard, director of commercial space policy at the National Space Council, during a panel discussion at the Global Satellite Servicing Forum October 19. That kicked off a discussion at the council meeting in September and the announcement of a 180-day timeframe for mission authorization.

She said that it was likely the administration would move quickly on this. While Harris’s comments at the council meeting suggested a 180-day deadline for offering proposals, Howard said she expected more than that by March. “We’ll have something from the executive branch by March 7,” she said, saying it would be “more formal” than a recommendation. “We’re on the clock.”

The satellite servicing field—more broadly, in-space servicing, assembly, and manufacturing, or ISAM—has also been watching an FCC proceeding opened this summer on how it might regulate ISAM missions. The “notice of inquiry” sought input on roles the FCC might play in licensing spectrum needed by ISAM missions, orbital debris regulations, and even roles it might play for ISAM missions beyond Earth orbit.

At the Global Satellite Servicing Forum, some saw a need for the FCC to address specific spectrum-related issues for ISAM. “We don’t have an allocation today for spectrum that ISAM services that can use,” said Joe Anderson, vice president of business development and operations at SpaceLogistics, the Northrop Grumman subsidiary that operates two Mission Extension Vehicles currently attached to Intelsat satellites in GEO.

For those two MEV missions, SpaceLogistics used Intelsat’s spectrum allocations for its satellites. “But going forward, as we start doing more servicing, we’re going to be maneuvering around much more frequently,” he said. “You need more assurance about access to spectrum.”

| “We need to have predictability, we need to have clarity and we need to have certainty in terms of the regulatory structure,” said Gold. |

Some, though, are worried the FCC, through the notice, might be seeking to take a greater role in overseeing ISAM missions. “They specifically ask what do they have authority for, and I know some people can look at that and take that as a sign that the FCC may try to overreach,” said Laura Cummings, regulatory affairs council at Astroscale US, a company working on satellite servicing systems. “I look at that and take that as a sign that this is my opportunity to tell the FCC that they are not a mission authorization body.”

Any solution that emerges from the mission authorization effort will likely need to be written into law. “It will end up taking an act of Congress,” she said.

“Get something out there, get something on paper, keep it moving forward, and then maybe we can talk about legislation a little bit further down the road,” said William Kowalski, chief operating officer of Atomos Space, on the same panel.

Graham, the former Senate staffer, also felt Congress will need to resolve the mission authorization issue. “That is something that will require Congress to speak to,” he said. “There’s some big questions to answer there about how we regulate and how we authorize these missions.”

Even some in the FCC have concerns they may be pushing the limits of their authority. “I’ve long expressed a little bit of skepticism about the FCC going alone here,” said commissioner Brendan Carr. “We need to make sure we’re leaning on the expertise of other agencies that do, in fact, have a cadre of rocket scientists to help inform this. I hope that we do that here.”

Companies, meanwhile, are looking for some certainty as they push ahead with new commercial space ventures. “We need to have predictability, we need to have clarity and we need to have certainty in terms of the regulatory structure,” said Mike Gold, executive vice president for civil space and external affairs at Redwire, at the Beyond Earth Symposium, warning of the challenges companies face today dealing with “absolute alphabet soup of agencies.”

“It’s vital that we consolidate and simplify not only because it makes it easier on the private sector,” he said, “it will also result in better safety and better innovation.”

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.