Since I was a young child Mars held a special fascination for me. It was so close and yet so faraway. I have never doubted that it once had advanced life and still has remnants of that life now. I am a dedicated member of the Mars Society,Norcal Mars Society National Space Society, Planetary Society, And the SETI Institute. I am a supporter of Explore Mars, Inc. I'm a great admirer of Elon Musk and SpaceX. I have a strong feeling that Space X will send a human to Mars first.

Thursday, March 31, 2022

Wednesday, March 30, 2022

Tuesday, March 29, 2022

Red Heaven: China Sets Its Sights On The Stars

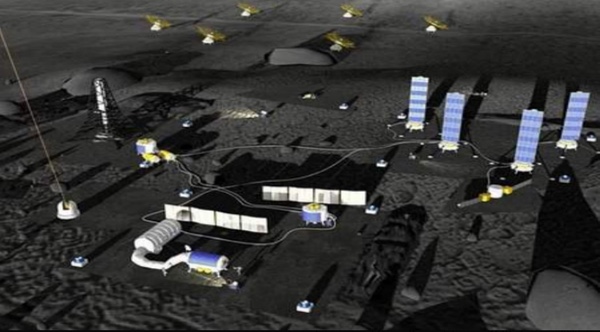

An illustration of what a proposed China-led international lunar research station might one day look like. (credit: CNSA) |

Red Heaven: China sets its sights on the stars (part 3)

by Jason Szeftel

Monday, March 28, 2022

Part 2 was published last week.

Starship: The state of the art

As it stands China is two generations behind SpaceX, and therefore the United States, in terms of launch technology. To catch up, China is trying to emulate American advances in both its old state organizations as well as in its new private, or at least quasi-private, companies. On the state side, it plans to catch up with the Falcon 9 by making its new Long March 8 rocket reusable. The aspirational date for this achievement is 2025. This is an optimistic but not entirely unreasonable timeline. Rocket landings already feel routine and by 2025 the reusable Falcon 9 will be a decade old. That is more than enough time to copy and imitate its systems.

| SpaceX’s rate of innovation is simply too rapid, and the technological gap now too large, for the Chinese space sector to catch up before the end of the decade. |

By that time, however, SpaceX will be operating Starship, leaving China behind once more. No new Chinese commercial company or state organization can change this. There is a yawning gap between Starship and all Chinese launch vehicles currently under development. Only a few Chinese commercial rocket companies are even working on medium-sized rockets. The rest are still developing their first small rockets.

To catch up to SpaceX these companies will have to first get comfortable with medium-sized rockets and then move on to heavy-lift rockets before finally taking a stab at super-heavy-lift rockets like Starship. There are no shortcuts here. Companies like iSpace, Landspace, and Galactic Energy are making progress but still lag very far behind. Even if they successfully reach orbit in 2022 or 2023, many formidable obstacles lie before them. Realistically, these companies are currently competing more with smaller American competitors like Rocket Lab, Firefly, or Relativity than with SpaceX.

SpaceX’s rate of innovation is simply too rapid, and the technological gap now too large, for the Chinese space sector to catch up before the end of the decade. If everything goes right China may start to catch up by around 2035. However, it may also never catch up. Launch vehicles take a very long time to develop and even copying SpaceX’s current designs, practices, and processes does not significantly speed up the process. SpaceX may make it look easy, but moving fast in space is hard.

SpaceX is also not sitting still. The operational Starship of 2030 will not be the Starship undergoing tests in 2022. Between 2010 and 2016 the Falcon 9’s payload capacity increased by more than 70%, and Starship has far more upgrade potential than the Falcon 9. There is every reason to expect large improvements to this already impressive launch vehicle. Even state planning and support can only do so much when aiming for such a fast-moving target.

China’s progress is very impressive compared to the rest of the world, but SpaceX has simply kicked the United States into another gear. While China caught up with the West in many industries, it did so in part because the rate of innovation in many sectors was declining. Trying to keep up with, let alone surpass, a pathbreaking company in a rapidly innovating sector is a totally different, and much harder, proposition. By 2022, the United States had at least three other reusable rockets under development in the medium- to heavy-lift category. To keep up China will have to do more than copy: it will have to first reach, and then compete at, the technological frontier.

For this to happen China needs its own innovative companies, and it needs them to struggle, experiment, and succeed just like American companies. Otherwise, it is in for a very long march using just state rockets. By updating its regulations and heavily backing dynamic private initiatives, China’s government has made the right moves. Its problem is that well over 90% of the Chinese space workforce works at state companies, leaving less than 10% available for work at private companies. Renovating an industry with a large state sector, while also keeping the state sector intact, is very hard to do and usually requires a Russian-style industrial reorganization.

For example, in the United States this ratio is reversed: only around 10% of the space workforce works for the American government. This gives breathing space to private enterprise and allows new companies to test out new products, services, and business models. Private firms and a large, flexible labor market balance out state technical direction and financial support, preventing the American space sector from being dominated by state organizations and state employees as in China. During the 2010s this unique mixture of high public financial support, plus real private innovation and corporate competition, created America’s modern dynamic space industry.

| China’s idealistic plan is to combine NASA’s commercial policies of the 2010s with China’s frequent state-led reconfigurations of key industrial sectors to create a world-beating space industry firmly under state control. |

China will struggle mightily to build a similar ecosystem because its space sector is completely dominated by two large state-owned enterprises with poor management, ineffective cost controls, and skewed incentive structures. Since the vast majority of China’s space workforce works at these, and other, state organizations, there are hard limits on how much the industry can evolve without major structural reforms. This is where the country’s real challenge lies. China has not yet figured out how to manage its state workforce, support new private industry, and compete with the United States all at the same time. Normally, a strategic industry like the space sector would see a more classic industrial reorganization of state organizations, but against the present American commercial competition that route would be self-defeating.

China’s idealistic plan is to combine NASA’s commercial policies of the 2010s with China’s frequent state-led reconfigurations of key industrial sectors to create a world-beating space industry firmly under state control. Unfortunately, its twin goals of commercial dynamism and state control are in conflict. In order to have both, China needs to repeat NASA’s commercialization policy of the 2010s but somehow do so without impairing its core state contractors. This is hard to accomplish because successful commercialization would, by definition, harm these organizations. In practice China will be forced to enact a more limited, and even compromised, version of NASA’s policies.

The limits of Chinese commercialization

China’s present compromise is to nurture private companies to create advanced new engines, space technologies, and rocket designs while pushing its state companies to up their game. It is using the threat of competition from private enterprise to try and improve these state organizations, just as NASA used new contracts with new companies to pressure its old defense contractors. However, even a decade later NASA’s old contractors have not emerged transformed. None of them are significantly more competitive today than they were when NASA’s commercial contracts were first announced. They remain the same companies they were in 2010.

China's state companies will not change either. In fact, they are far less likely to transform in the 2020s than American defense contractors were during the 2010s. What improvements these American companies did make came as a response to very real threats to their businesses. Chinese state companies, by comparison, face no real competitive threat and have a correspondingly smaller incentive to evolve. They are designed to respond to top-down shifts in Chinese political priorities and industrial policy goals, not to authentic corporate competition.

The only reason they are feeling any pressure at all is because the Chinese government sees the United States, and the American space sector, as a competitive threat. Without this broader strategic threat China’s state companies would keep plodding along without a care in the world. But in light of new American capabilities, CASC and CASIC suddenly face serious political pressure to evolve.

While these organizations themselves will not change, the state can push them to duplicate American capabilities as much as possible. Chinese state organizations are actually quite capable of eventually doing this, so long as they are pushed early, long, and hard. Where the United States needs commercial competition to enact major changes, China can get a lot of bang for its buck just by demanding state industry emulate successful foreign products. However, if the goal is to create a more broadly competitive and innovative space industry over the long term, then Chinese state companies are as much in need of an overhaul as the original Long March 9.

Yet nothing China has done since 2014 suggests it is planning to truly overhaul these gargantuan state-owned enterprises, which produce everything from missiles to drones to heavy machinery to medical equipment to satellites. What it has done instead is enact some relatively minor industrial changes to the sector. While heavy marketing and propaganda blanket this commercialization effort, it is not as deep or substantial as it seems. Strip away the publicity and the true goal is not revealed to be a structural transformation of the Chinese space sector. Rather, China clearly plans to stick with the same underlying industrial structure for the long haul.

| China fostered its new commercial space ecosystem before it saw how fast and how far SpaceX would go. |

Over time, China’s state sector will absorb or discard much of the commercial industry. As mentioned earlier, this will probably involve a period of semi-commercial experimentation followed by state-directed reorganization afterwards. The Chinese government simply cannot sustain an enormous space sector and a capital-intensive private sector forever, and probably not even for ten more years. The state sector is already large and inefficient. Adding in more companies means even more redundancies and misallocated capital, as well as eventual tensions with state organizations.

When the Chinese central government signaled its interest in space, it prompted a feeding frenzy to develop in the sector. Companies, localities, and individuals all clamored to access the cheap credit surging into the industry. Local governments partnered with companies and universities to try and develop high-tech space industries in their region. Provinces engaged in vicious competition to gain a foothold in what was touted as the next great industry of the future. Everyone sought the status, prestige, and attention associated with developing products on the technological frontier.

As in the electric car sector, the result was a massive oversupply of new space companies in general and new rocket companies in particular. Unlike in the United States, most of this investment is not primarily, or even secondarily, concerned with profit potential. Industry experts think the global launch market, excluding China, can support fewer than ten launch vehicles, perhaps three in each payload class, and most of these slots are already taken. Chinese companies are therefore not scrambling to be selected by the market, but by the state. They know that when the commercial experimentation period is over, successful projects, along with iconic brands or products, will be brought deeper into the state fold while funding for the rest quietly dries up.

This is especially likely to happen when state companies are already pursuing so many similar technologies. Chinese state companies are visibly and publicly emulating as many of SpaceX’s innovations as possible. For example, in addition to trying to land their rockets, they have begun catching fairings. At some point it makes sense to ask: exactly how many small rockets or Falcon 9 clones does a single country need? With more than 150 small launch vehicles in development around the world it would be an understatement to say there is a coming rocket glut.

China also has no reason to run this experiment forever. Launch vehicles are not essential in and of themselves: they are essential because of what they bring to orbit. They are important because they enable access to space. This means China does not really need to beat SpaceX or the American space launch sector. While that would be exceedingly gratifying, it just needs to make sure its launch sector does not fall too far behind American capabilities. It only really needs to produce rockets that allow it to send roughly comparable payloads to orbit at a roughly comparable cost and frequency.

Anything more would be a great victory, but this victory is now largely out of reach. China fostered its new commercial space ecosystem before it saw how fast and how far SpaceX would go. Back in 2014 the company had not yet landed the Falcon 9. At the time it may have seemed plausible that China could reach technological parity with the United States during the 2020s. Now, with Starship on its way, producing multiple Falcon 9 clones in the late 2020s would no longer show how advanced China is, but how far behind it remains.

The only way for China to keep up is to finally bite the bullet and painfully restructure its state companies. This move could allow a similarly dynamic, competitive space industry to develop. However, as in Russia, it is unlikely to succeed in practice and would cause serious harm to the Chinese space sector in the process. For China, real commercialization and privatization is simply too risky. Today NASA’s commercialization initiative looks like a great success story, but it easily could have gone awry and left the American government without key capabilities for many years.

The American military, which runs America’s other space program, rejected these risks, and China’s military, which runs its space program and is wedded at the hip to its state space companies, is even more wary.

Rather than a risky overhaul, China is choosing the strategy that lets it wring as much as possible out of the space sector while still keeping its basic structure intact. This plan is also a much better fit for China’s current political, economic, and industrial model. State direction plus boundless credit in a quasi-commercial environment is a tried-and-true Chinese development strategy. The government knows it will have far more success copying current and proposed American systems than it will in creating a similarly innovative Chinese space sector. Limited money, limited time, and a limited probability of success all push the government to stick with what has worked so far.

Foreign observers tend to see far more commercial potential in the Chinese space sector than truly exists. Building a whole private value chain from scratch in a totally state-dominated strategic sector is exceedingly difficult. Zero major commercial space enterprises existed in China back in 2013. Even today, most Chinese commercial space enterprises are just doing contract work for state corporations. Creating a real private value chain in the sector would mean transforming employment patterns, procurement methods, and basic institutional processes all at once.

With so much required, and so much at stake, China, like Russia, has reasonably balked at pursuing this path.

| Even the United States only managed to create a dynamic commercial space sector by the skin of its teeth: its space industry is littered with the carcasses of optimistic new space companies. SpaceX managed to break through, but only by barreling through many nail-biting moments and close calls with bankruptcy. |

Unlike the United States, China is not dealing with an old industry. The Chinese space sector is still relatively young and is just now reaching its stride. Before 2010, it averaged fewer than 10 launches a year. During the 2010s it rapidly scaled up the tempo and by 2022 China could launch more than 50 rockets a year. Any suggestion that the whole thing must be rebuilt from the ground up is a very bitter pill for the Chinese government to swallow. Doing so would mean destroying all the institutional knowledge it has only recently built up in launch vehicle development, production, and operations.

Add in the overwhelming probability of failure and it seems downright insane. Even the United States only managed to create a dynamic commercial space sector by the skin of its teeth: its space industry is littered with the carcasses of optimistic new space companies. SpaceX managed to break through, but only by barreling through many nail-biting moments and close calls with bankruptcy. It also took the company nearly 20 years to get to the point where it could launch 30 orbital rockets a year. China does not have 20 years to wait or a stomach for endless near-failure.

China’s recent commercial initiatives are an effort to set the industry on as competitive a path as possible before the state once more closes ranks around its state organizations. In the end, all of the real legwork in the Chinese space program will still eventually be done by the state. Until then, the plan is to use quasi-commercial companies, as well as other means like industrial espionage, to get the overall level of space technology in China as close to the state of the art as possible.

Conclusion

Even if it does not surpass the United States, China will still gain many benefits from reconfiguring its space sector with new capital, firms, and commercial processes. These moves will encourage more innovation, rapid prototyping, and experimentation, or at least more nimble imitation, throughout the sector. They will also push the industry to seize many of the new downstream business opportunities opened up by reusable launch vehicles. Had China merely stuck to its earlier plan of copying the final version of SLS by 2030, then it would be in a much less advantageous position. Instead, China’s strong response to SpaceX will, at the very least, energize and transform its space sector for the better.

A major benefit will be lower costs. National space programs are enormously expensive, and the more ambitious they grow the more expensive they become. For example, at the height of the Apollo program the United States spent 4% of its GDP on NASA: in today’s dollars this sum would be larger than the GDP of 85% of countries. All told, fewer than ten countries can really afford a serious space program. Exclude international consortiums and it shrinks to less than five countries.

China’s costs have likewise grown along with its ambitions. Commercial satellites, military satellites, space stations, lunar missions, and Mars probes are not cheap. Keeping this expanding space program affordable is a key government priority. The Chinese government envies the price reductions it sees in the American launch sector and is willing to pay a heavy price up front to reap something similar later on. Even if nothing else pans out, China’s quasi-private space launch companies will be deemed a success if they help to significantly reduce the state’s ever-growing launch costs over the long term.

Lowering launch costs in turn creates a feedback loop to grow the overall launch market. The improved launch economics of reusable rockets have already opened up many new commercial opportunities like low Earth orbit (LEO) Internet constellations. New space-based businesses are spawning every year to try and capture some of these opportunities. Optimistic projections about the viability of such businesses have pushed banks to project that a trillion-dollar, or even a multitrillion-dollar, space industry will emerge in the coming years. Unsurprisingly, China has every intention of ensuring similarly lucrative projects come to fruition within its borders.

Cheaper access to space means, among other things, many, many more satellites. Cheap rocket launches have fused with the even older trend of building and deploying many small satellites in a single launch. Once reusable rockets started sending dozens of small satellites into orbit at once, the result was a veritable explosion in the number of satellites orbiting the Earth. Between 2010 and 2020 the number of satellites in orbit increased by 252%. The year 2021 alone saw more orbital launches and satellite deployments than any previous year, including the former Cold War peaks of the 1960s and 1970s.

However, this is nothing compared to what is coming: even conservative market research groups project a 450% increase in orbital launches during the 2020s compared to the 2010s. Other estimates suggest more than 100,000 satellites could be in orbit by 2030.

Together reusable rockets, lower launch costs, and increased satellite launches are catalyzing a revolution in satellite manufacturing. We are moving from a world where hundreds of satellites are produced a year to one where thousands, and maybe even tens of thousands, are produced every year. To make this happen a sea change in the satellite industry is currently underway. The satellite industry, as a commercial and industrial sector, is undergoing a revolution similar to what happened in the launch market during the 2010s.

| As with electric vehicles and 5G infrastructure, a potential step change in the satellite manufacturing sector could be the boost China needs to make it to the front of the pack. |

To accommodate high volume production, satellite manufacturing is shifting from producing a few excellent, well-crafted satellites to producing many interchangeable, standardized satellites. Satellite designs and manufacturing processes are focusing on throughput, efficiency, and scalability rather than long service life and superlative engineering. In the process satellites are becoming digital, modular, mass-produced products. They are becoming cheaper to produce, quicker to manufacture, and easier to adjust once in orbit. Together these changes will make satellite networks more capable, flexible, and responsive.

A few high-volume satellite factories are already online. In 2019, OneWeb and Airbus began producing two satellites a day at a new factory in Florida. In 2020, SpaceX started producing four Starlink satellites a day at its own facility near Seattle. Production rates like these are unprecedented. The previous peak rate for satellite production at a single factory was only around six satellites a month. The industry has already seen an 20-times improvement in throughput, and this is only the beginning.

Once more SpaceX is leading the way. After launching its first experimental Starlink satellites in 2019, SpaceX quickly became the largest satellite manufacturer and operator in the world. In 2022 SpaceX alone could produce and launch more satellites in one year than the whole world had produced or launched in total before 2013. As with reusable rockets, this shift sent ripples throughout the global ecosystem of satellite users and manufacturers. While many companies and countries are attempting a response, China is once again moving harder and faster than most other competitors.

China sees these changes as a threat, as yet another area where it may fall behind, but also as an opportunity to leap past its current limitation in satellite manufacturing. As with electric vehicles and 5G infrastructure, a potential step change in the satellite manufacturing sector could be the boost China needs to make it to the front of the pack. As a result, China is investing heavily in new satellites and new satellite production methods: satellite design, development, and operations make up more than a third of total Chinese commercial space investments. Along with launch technologies, satellite manufacturing is the other hot investment in the Chinese space sector, with most provinces and innumerable companies trying to get in on it.

This trend accelerated in 2020 when China declared advanced satellite networks a key element of national infrastructure. Later that year, a CASC official claimed that China would launch 4,000 satellites into orbit within the next five to ten years. While this had once seemed unlikely, since it was ten times the total number of satellites the country had in orbit at the time, China is already aiming even higher: it has announced plans to create a state-owned version of SpaceX’s Starlink Internet constellation made up of more than 13,000 satellites. Yet even this massive constellation is also only one part of an even larger plan for an interconnected network of state-owned communications, navigation, and earth observation satellites.

Yes, in the coming years the Chinese state is planning to blanket the skies with satellites.

Launching more than 10,000 satellites for a reasonable price, however, requires reusable launch vehicles—preferably large, rapidly, and fully reusable launch vehicles like Starship. This is a big reason why, for all the talk of satellites and future commercial ventures, in 2020 61% of all investment in Chinese space companies went towards launch-related companies. Launch constraints are the limiting factor on all other space activities. Making grand plans for novel space systems is pointless without solving the launch problem. China simply needs better launch efficiencies to make its most extravagant space dreams come true.

These dreams are also not primarily commercial dreams.

While China cares about the many new commercial possibilities created by reusable rockets and large satellite constellations, it cares far more about the strategic and military implications of these innovations. It bears repeating that the Chinese space sector is not a civilian operation. CASC and CASIC report to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). PLA offices are embedded within CASC and CASIC design departments, research institutes, and factories. All new Chinese space assets exist to enhance state power and, in the final analysis, fall under the purview of the Chinese military.

| The harsh truth is that space is not a peaceful celestial commons open to all nations but a hotly contested military domain. |

China may hype up its Moon bases and space stations, but these are mostly propaganda moves to nurture national pride and demonstrate national power. China’s focus in space remains fundamentally military in nature. China is concentrating resources on new space launch vehicles and satellite payloads not because of commercial opportunities, but because space remains a strategic arena and a key military domain. As in 1991, the present and future contours of warfare are bound up with new space technologies. Countries without advanced military space assets, and the ability to threaten their enemies’ assets, will be in a perilous position during any future military conflict.

Space is essential for almost every military function, from command, control, and communications to positioning, navigation, and timing to intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. Satellite networks distribute information between disparate military command centers, weapons platforms, and sensors. They create spatial maps of the battlefield and link distant military units together. They guide hypersonic missiles to their targets and may even be able to track stealth aircraft. While many mocked it initially, President Trump’s Space Force was not only maintained by President Biden, but also imitated by the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. Russia and China likewise created—or, in Russia’s case, recreated—their respective Space Forces in 2015.

The harsh truth is that space is not a peaceful celestial commons open to all nations but a hotly contested military domain. Space is the ultimate high ground. Just as navies seek command of the seas and air forces seek air superiority, militaries now require space supremacy as well. This inescapable fact has turned space into a military arena. Media reports often inaccurately describe space as on its way to becoming militarized when it is in fact already heavily militarized, and grows more so every year. The large annual growth in military space budgets, not to mention the even larger annual growth in classified military space programs, are building upon decades of earlier investments.

Both the American and Chinese militaries explicitly view space as a military domain. This is why the American government has regulated the sale of satellite technologies for close to half a century. It has actively sought to limit the number of countries with operational satellites and, more importantly, satellite manufacturing capabilities. The United States also prefers, and has worked to create, a world where fewer than ten countries have their own indigenous satellite launch capabilities. These overarching security policies even apply to American allies, who are regularly encouraged to be dependent on American networks and systems rather than to develop their own.

China has likewise sought to assure its own use of, and access to, space while restricting that of other countries. Denying enemies the use of space is a key part of its military strategy. It wants its foes to have no more freedom to operate in space than in China’s coastal waters. Over the years this means it has developed precisely the space capabilities that the American government most fears. While no potentially hostile state has yet been able to credibly threaten American space networks, China now most certainly can.

China has invested heavily in technologies to target and destroy hostile foreign space infrastructure. It has an operational ability to destroy enemy satellites as well as a stockpile of missiles for the job. The classic cross-fertilization between military systems and space technologies still holds: rockets, particularly solid rockets, are not only vehicles for taking satellites into orbit but also missiles that can destroy enemy satellites. Alongside missiles China can use satellites, lasers, microwave weapons, electronic jammers, cyberweapons, and other advanced techniques to take out enemy satellites. In short, China has a veritable arsenal of anti-satellite weapons.

Anti-satellite weaponry is also one of the technical areas where China is likely ahead of the United States. America has not invested as much in such weapons because, until recently, few competitor states even possessed advanced space networks. Meanwhile, China invested significant resources into this effort because the United States is extraordinarily vulnerable to being denied the use of space. Without its space-based networks the US military cannot function as a global expeditionary force or durably project power far from North America. As a result, countries like China and Russia have long viewed the extreme American dependence on space as a potential Achilles heel to target during a conflict.

However, the American military is now responding to China’s capabilities by making its systems more resilient, adaptable, and mobile. Most American military satellite networks are currently composed of a relatively small number of vulnerable and hard to replace satellites. Over time these legacy systems will be supplemented with new systems composed of cheap, standardized, and easily replaced satellites. This new, hybrid system will make American military space networks more robust, redundant, and survivable. Theoretically, high volume satellite production lines could even feed large, rapidly reusable launch vehicles to replenish and maintain military space networks during a conflict.

So just as in the commercial sphere, large, rapidly deployable satellite constellations are changing the future architecture of military space networks. These changes are not limited to survivability. New military satellite networks also promise large improvements in network performance and utility. As they combine with enhanced terrestrial networks like 5G Internet, and new weapons platforms, these improvements will enable powerful new ways of waging war. In the process, they will also further increase the centrality of space to military operations, a trend which has not slowed for over 30 years.

Space is actually about to become even more important to the United States. The American military is in the early stages of a crucial, once-in-a-generation shift in its command, control, and communication systems. During this process, the many diverse networks spread across different military branches and organizations will be merged into one interoperable system. Formerly disconnected and non-communicating systems will be brought together into an increasingly unified information system. Over time, everything from satellite ground stations to naval command centers will be integrated into global cloud networks. When this process is complete, space, as well as cyberspace, will be the glue that binds the American military into a unified whole.

As a result, any real war between the United States and China means a conflict in space. There is no avoiding it. However, even during a hypothetical future conflict Starship once more provides the United States with a dramatic leap in space capabilities. Starship not only enables these vast new distributed satellite networks, but would also be, among other things, the primary means of replenishing them during a conflict. Its launch capacity and tempo would dwarf anything China could muster, and this difference in capability would likely be a deterrent in and of itself.

| For this narrative to stick China has to actually be on its way to being number one. While this seemed plausible back in the early 2010s, when the American space program was comparatively rudderless and listless, that era is long gone. |

Yet even in the absence of a future military conflict, Starship remains a major irritant to China. China wants the rest of the world to eventually recognize its celestial eminence. Unlike the United States it does not want to spread the fruits of space science and technology, or jobs in its space labor force, around the world. It would rather leverage its superior space capabilities to dazzle, influence, and subordinate other nations. It is also totally uninterested in creating any sort of coalition of spacefaring nations. What China really wants most of all is to be number one, to be acknowledged as the number one spacefaring nation by all other nations, and to bask in the glow, and the political rewards, of this admiration.

To that end, China has deliberately chosen science and technology missions that allow it to claim historic firsts, such as landing on the far side of the Moon. These historic firsts help it to convince its people, as well as the rest of the world, that China is pushing the boundaries of space science and technology. In reality, rather than breaking new ground, the Chinese space program is mostly combing through old American, Soviet, Japanese, and European science missions to find noteworthy gaps it can fill. Or it is retreading old ground other space programs have already covered, such as space stations, but which still seem impressive and novel. Nonetheless, these projects help to create a narrative of China’s coming, and even inevitable, preeminence in space.

However, for this narrative to stick China has to actually be on its way to being number one. While this seemed plausible back in the early 2010s, when the American space program was comparatively rudderless and listless, that era is long gone. The shift to a more commercial American space industry has fundamentally changed both the narrative and the technological reality in space. Put simply, Starship, and everything it enables, makes China a clear number two in space. Soon the truly novel, historic, and impressive activities it makes possible will completely unravel the narrative of China’s celestial ascent.

If multiple private American space stations are constructed and then regularly serviced by multiple private spacecraft, then China’s single space station based on an old Russian design will no longer seem all that impressive. If NASA creates a real Moon base with large Starships serving as structures and transportation systems, then China’s small Moon rovers will seem passé. If unprecedented new Starship missions, a successful Artemis program, or a SpaceX collaboration with NASA on Mars exploration, push the Chinese space enterprise firmly into the rearview mirror, then China’s goal of space preeminence will drift out of reach. Very soon China’s space program will no longer look like it is rapidly closing the gap with the American program. Starship is about to empower a new era of space operations that will leave China in the dust.

China can only respond by either matching these American efforts or else by meekly lowering its ambitions. If China is clearly outshined in space, despite all its enormous investments of time, money, and political capital, then it will most likely pare back its wide-ranging investments in the sector. Just as the Soviet Union scaled back many of its space programs after its Moon program failed, China will refocus its energies. Once core propaganda goals are no longer being met, more obviously valuable investments, such as those with significant and immediate military uses, will get the nod. In other words, when Chinese space science and technology projects lose their propaganda value, and their appearance of being cutting-edge, then they will lose some of their budget resources as well.

Since China sees space technology as an opportunity to advance its prestige, it has no interest in playing a clear second fiddle to another country. It also has little interest in contributing to some abstract global space community if it is not on its way to being at the top of that community. As in many other areas, China’s aspirational goal for being number one in space is around 2049. This far off date, the 100th anniversary of the formation of the People’s Republic, is politically useful. It is distant enough to let the government say that China is making sufficient progress while also giving it cover to suggest that it has more than enough time.

Time, however, is not on China’s side.

After many years of dim and fuzzy purpose, clarity and focus is finally returning to the American space enterprise. Alongside SpaceX, China has been the best thing to happen to NASA in a very long time. The agency once more has a strategic competitor it can use to justify grand plans and large budgets. For the first time in decades, it is also seeing policy continuity between administrations. After the Trump Administration decided to use NASA’s Artemis program to demonstrably outclass China in space by creating a sustainable presence on the Moon, the Biden Administration reaffirmed this decision.

In fact, both halves of the American space program, civilian and military, are energized as never before. The new Space Force is consolidating many small, separate military space agencies into one large unified branch of the American armed services. With clear vulnerabilities, threats, and objectives, as well as less bureaucratic overhead and institutional inertia, the Space Force is poised to significantly improve and modernize US military space capabilities in the coming years. It is also developing in light of NASA’s commercial successes, which gives it the precedent and the motivation to bring innovative commercial processes into the ossified world of military procurement. If it makes the right moves and takes advantage of the present commercial enthusiasm and strategic importance of space, the results could be as revolutionary for the new Space Force as they have been for NASA.

| Taken together, this means there will be no space diplomacy. Tensions will only ease once the present conflict between China and the United States plays itself out. |

Little galvanizes the United States like an apparent strategic competitor. After decades of permissive accommodation, the American government as a whole is now setting its sights on China. It is overtly using the threat posed by China to justify massive new investments in strategic areas such as the space sector. The NASA administrator and the head of the Space Force are jointly signing off on reports saying the American space industry must be strengthened in light of Chinese advances. Most tellingly of all, the United States is even heading back to the Moon to conclusively reestablish American preeminence in space science and technology.

As President Johnson said, “In the eyes of the world, first in space means first period; second in space is second in everything.” Both China and the United States have taken this statement to heart. Both have also decided that the Moon will once more be the site of their symbolic victory. While NASA’s Artemis program is currently a Frankenstein assemblage of different policies, ideas, and systems from different administrations, it will be progressively rationalized during this period of strategic competition. Just as in the Cold War, major military threats from space undermine America’s presumed geographic insulation and, like terrorism, weapons of mass destruction, and cyber attacks, tend to provoke a disproportionate American response. Viewed from this light, China’s notional plan for a joint Moon base with Russia seems almost designed to provoke an intense, even paranoid, American reaction.

Taken together, this means there will be no space diplomacy. Tensions will only ease once the present conflict between China and the United States plays itself out. Until one country decisively claims the first-place trophy, or else sees its rival clearly stumble and fall, this new space race will go on. Just like during the Cold War, the world will be better off if this political confrontation is decided with a symbolic contest rather than a military conflict. Since space programs are far less costly than wars, and can leave behind great legacies, let’s hope this new space race stays symbolic but runs hot: advancing many new technologies, pushing humans farther out into the solar system, and giving the species a few more iconic achievements before finally, and inevitably, burning itself out.

Jason Szeftel is a writer, podcaster, and consultant. His book on China is coming out later this year.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Dark Clouds-The Secret Meteorological Satellite Program

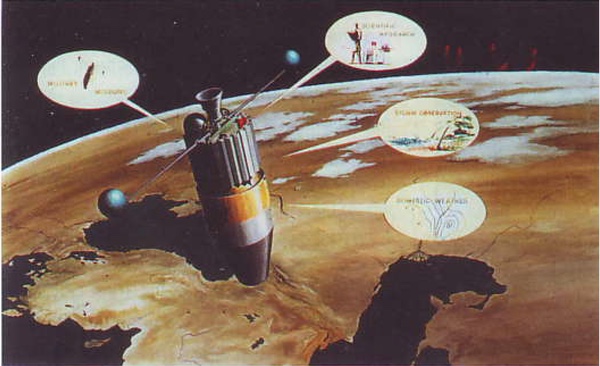

This Lockheed illustration from 1959 shows the possible uses of a photographic satellite. Although the reproduction is poor, it illustrates that in addition to military reconnaissance, such a satellite could also be used for monitoring crops and forests, and weather prediction. (credit: Lockheed via the NRO) |

Dark clouds: The secret meteorological satellite program (part 1)

The RAND Corporation and cloud reconnaissance

by Dwayne Day

Monday, March 28, 2022

Amrom Katz was a short, energetic, outspoken physicist who worked for the RAND Corporation in the 1950s. RAND was located in the Los Angeles oceanside suburb of Santa Monica, California. It was a “think tank” where engineers, scientists, and policy experts studied advanced technologies and ideas for the US Air Force. At lunch, RAND’s thinkers would sip margaritas at a beachside bar and then return to their offices to think about nuclear war, earning the moniker “wizards of Armageddon.”

| In this particular draft, Katz recommended that the Air Force begin a “cloud reconnaissance satellite” as soon as possible. Katz suggested that the service specifically not call it a “weather satellite,” because an accurate title would create problems. |

Much of what RAND did during the 1950s concerned developing strategies for targeting, using, and protecting Air Force strategic weapons. But the think tank also had a small group of experts devoted to the subject of strategic reconnaissance and Katz and his thinking buddy Merton Davies were the lead wizards in this area. Although Katz was rarely the first person to come up with an idea, he was often the first person to study it in a comprehensive manner and recommend what the Air Force should do. Sometimes, but less often than Katz liked, they took his advice. In March 1959, Katz wrote an internal RAND “draft” document about weather satellites.

RAND drafts were actually discussion papers, not intended for external release, and unlike most bureaucratic documents, Katz’s drafts were often filled with wry, slightly sarcastic remarks about the military bureaucracy. RAND was far from the Washington power corridors, which was disadvantageous in some ways. But as Katz once wrote, from their detached perch above the bureaucratic fray, “sometimes the view is tremendous.”

In this particular draft, Katz recommended that the Air Force begin a “cloud reconnaissance satellite” as soon as possible. Katz suggested that the service specifically not call it a “weather satellite,” because an accurate title would create problems. “If we claim this is a weather or meteorological satellite,” he wrote, “various political and jurisdictional hackles at NASA and DoD and U.S. Weather Bureau levels will rise to the occasion. This we really don’t need. We feel that sleeping hackles should be left lying.”[1]

Katz also outlined the reasons why an Air Force “cloud reconnaissance satellite” would be useful for the Air Force. But what he did not know was that not only were the bureaucratic squabbles more complex than he imagined, but in spring 1959 the Air Force was strangely indifferent to the idea of a military meteorological satellite. It would take several years for this attitude to change in the Air Force, but Katz's arguments were prescient. Amrom Katz was being reminded of something he knew only too well: it was lonely being ahead of your time.

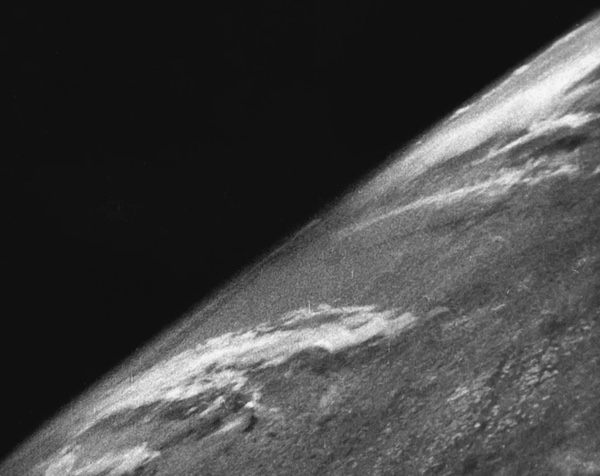

One of the first images taken from above the Earth's atmosphere. A camera in a V-2 rocket recorded this image in 1946. Later studies of these images were used to determine if photographing clouds from above would be useful for weather prediction. Early studies were inconclusive. (credit: US Army) |

Wizards of space

RAND was the first and most important of the many think tanks that so heavily influenced American defense policy during the Cold War. Established in 1946 by the Douglas Aircraft Company at the urging of the Army Air Force leadership, Project RAND was intended to provide suggestions on future technology to assist the Air Force. In its very first proposal produced soon after Project RAND was formed in 1946, RAND’s engineers recommended that the Air Force build an Earth-circling satellite. Meteorology and reconnaissance were the two primary missions for such a satellite.[2] But the cost of such a vehicle, and particularly the rocket needed to place it in orbit, was enormous, so the Air Force did not approve the project. For the next several years, RAND’s experts explored various aspects of the technology needed to make a satellite work, researching structures, engines, and propulsion. But these remained primarily paper studies.

| A weather satellite would be restricted largely to photographing clouds. But from a weatherman’s viewpoint in 1951, cloud pictures were largely useless. |

In April 1951, RAND experts produced the first of their two early comprehensive studies on the missions of satellites, defining in detail exactly what they could do from orbit. The first report, titled “Inquiry into the Feasibility of Weather Reconnaissance From a Satellite Vehicle,” evaluated the value of weather data that could be returned from a television-based weather satellite.[3] It was not an attempt to design a satellite, merely to determine if any of the data that it could collect would be useful for “weather reconnaissance.” The report's authors, William Kellogg and Stanley Greenfield, stated that, “in the event of armed conflict, aerial weather reconnaissance over enemy territory, similar to that obtained in World War II, will be extremely difficult, if not impossible. An alternative method of obtaining this information, however, is thought to lie in the use of the proposed satellite vehicle.”[4]

But Kellogg and Greenfield recognized that such a satellite would be controversial in the weather community. Meteorology relied upon direct measurement over large areas: wind speed and direction, air pressure, humidity, and temperature. Meteorologists gathered this data by going places and taking readings, or sending balloons up to do this for them. This information was incorporated into mathematical models to predict what would happen.

A weather satellite was different. It did not take direct measurements. It flew high above the atmosphere and took pictures. “It is obvious,” Kellogg and Greenfield wrote, “that in observing the weather through the ‘eye’ of a high-altitude robot almost all the qualitative measurements usually associated with meteorology must fall by the wayside.”[5]

A weather satellite would be restricted largely to photographing clouds. But from a weatherman’s viewpoint in 1951, cloud pictures were largely useless. The presence or absence of clouds provided only minimal data about the weather. Clouds did not often indicate wind direction or velocity, particularly at multiple altitudes. Because meteorologists considered clouds relatively unimportant, they had devoted little attention to their study. Only two years earlier, an article by Army Major D.L. Crowson in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society had addressed this dilemma. Crowson, using photographs from high-altitude V-2 rocket flights in the Nevada desert, argued that even low-resolution cloud imagery from high altitudes could be useful for weather forecasting. But Crowson’s 1949 article did not convince anyone that the limited information that could be collected was worth the costs either of using rocket flights to carry cameras to high altitude, or of taking the next step and developing a satellite and a rocket capable of placing it in orbit.

Kellogg and Greenfield decided to pick up the argument where Crowson had left off. They posited a satellite in a 350-nautical-mile (648-kilometer) orbit and equipped with a standard television camera and asked a very basic question: “Can enough be seen from such an altitude to enable an intelligent, usable weather (cloud) observation to be made, and what can be determined from these observations?”[6] They set up a simple test: they took some of the same data that Crowson had used and attempted to determine what the likely weather pattern was for the American southwest when the observations were made. They then compared their forecast based on the cloud data to the actual weather patterns reported on those dates. The results did not produce a clear endorsement of a weather satellite. They concluded that the data that could be obtained from cloud observations was limited, but this was due in part to the lack of scientific study of how clouds reflected weather patterns. With better information cloud photography might be more valuable, but that data could only be gathered with a satellite, a conundrum for meteorologists. Nevertheless, a weather satellite offered some unique advantages to meteorology, particularly for observing areas of the Earth for which little data was available. “Although ship reports and weather reconnaissance by aircraft help to some extent to fill the gap,” they wrote, “there has long been a need for extending weather observations over the oceans and inaccessible areas.”[7]

Such a satellite also meant that “extremely large areas may be visually observed in a relatively short period of time.” Furthermore, “for the first time in the history of synoptic meteorology, the classical models of various weather situations may be examined in toto.”[8] In other words, a satellite would help not just weather prediction, but the testing of weather models. It could be a research tool, not just a measurement instrument.

The bigger problem was that the Air Force leadership had no interest in satellites of any kind. Although the potential utility of satellites was murky, their expense was obvious. RAND was told to continue its studies and focus primarily on reconnaissance. But the Air Force would not start a program to develop actual hardware. By 1954, RAND produced a much more extensive report known as Feed Back, which evaluated the design and utility of a reconnaissance satellite. Feed Back led the Air Force to begin a reconnaissance satellite program in 1955 that it soon labelled Weapons System 117L, or WS-117L. But the project limped on for several years, grossly underfunded.[9]

In early 1956, the Air Force selected Lockheed to build the reconnaissance satellite instead of Martin Co. or the Radio Corporation of America, or RCA. In their contract proposals, both Martin and RCA had briefly mentioned meteorology as one possible use of a visual reconnaissance system, but they were primarily focused on the reconnaissance mission. Lockheed was given a contract to develop a reconnaissance satellite as part of WS-117L. But the program was underfunded and Lockheed was not provided sufficient money to proceed.

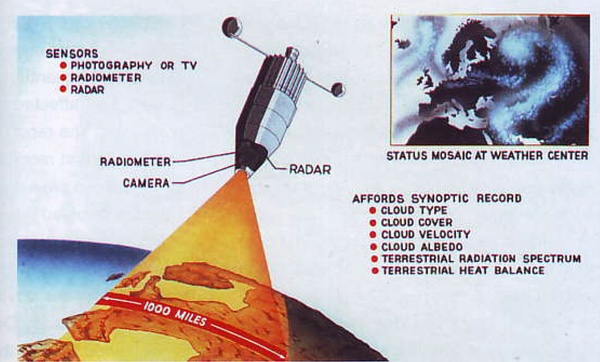

Although early studies of a satellite for meteorology used television cameras, soon scientists proposed adding additional instruments to image other atmospheric effects. This illustration is from 1959 or 1960 and shows a vehicle based upon the USAF’s Samos reconnaissance satellite and its Agena spacecraft. (credit: Lockheed via the NRO) |

A stationary front

For ten years starting in 1946, RAND's engineers had studied the problems of spaceflight and reconnaissance for the Air Force. But RAND’s studies were not limited to satellites. The think tank addressed many other subjects as well and, in December 1956, RAND produced another report that attempted to quantify how reconnaissance in general was affected by different weather conditions. The report had been prompted in part by the first reconnaissance robots, an aerial balloon project known as “Genetrix.” Genetrix involved releasing hundreds of balloons carrying cameras in Europe. Prevailing winds at high altitudes carried the balloons over the Soviet Union and upon reaching the Pacific Ocean they were commanded to drop their camera payloads for retrieval. Most of the balloons never made it, but for the few that did, many of their photographs were degraded by clouds.

| The bigger problem was that the Air Force leadership had no interest in satellites of any kind. Although the potential utility of satellites was murky, their expense was obvious. |

The robots could not determine if there was a cloud obscuring the target. RAND's study pointed this out and addressed the full spectrum of reconnaissance, from visual and infrared to radar, no matter what platform was used to carry the sensor. As the study's author noted, weather was a big problem for reconnaissance. But some areas of the globe were far more likely to be cloud-covered than others, and reconnaissance sensors such as infrared detectors or radar would be affected differently depending upon the type of weather phenomenon.

The author's primary conclusion, however, was that reconnaissance experts needed to further study the problem in detail, and at the very least develop a better definition of the problem and a unique set of weather criteria for different kinds of reconnaissance operations.

Current military weather criteria were insufficient. For instance, a military officer planning a reconnaissance mission would consider clouds over a target to be “critical weather,” whereas high winds would be unimportant. But a weatherman supporting a bombing mission might have little concern about clouds but consider high winds to be unacceptable.[10] In their losing bids for the reconnaissance satellite contract, both Martin and RCA had specifically addressed the problem of cloud cover over the Soviet Union, acknowledging that this would present a problem for a reconnaissance satellite. Both companies proposed satellites using television cameras, and both recommended solving the cloud cover problem essentially the same way, through brute force: launch enough satellites and take enough photographs and eventually all of the important targets would be photographed over a period of time. But such a brute force method would return massive numbers of photographs and some kind of automated sorting system would be required to assess them and discard cloud-filled photographs. Equally important, this could mean long delays to obtain photographs of certain areas.[11]

The Air Force WS-117L satellite program managers realized that a weather satellite would be useful, both to support worldwide Air Force operations, and to support their own reconnaissance mission. But WS-117L was severely underfunded in 1956 and 1957. The Air Force would not provide the program office, or Lockheed, with more than a fraction of the money necessary to build the satellite. With no money to pay for even the basic development of a reconnaissance satellite, they certainly could not consider developing a weather satellite to support it.[12]

What changed things was the October 1957 launch of Sputnik. Suddenly WS-117L was force-fed with money by the Air Force leadership. Soon Air Force officials split WS-117L into three programs known as Sentry, Midas, and Discoverer. Sentry was the reconnaissance satellite program, Midas was a missile warning satellite, and Discoverer was merely a cover story—essentially a lie—to conceal the CORONA reconnaissance satellite program. Sentry also began to evolve and grow. At first it consisted of only two basic satellite designs, the Pioneer and Advanced reconnaissance cameras. But by the end of 1958 its name had been changed to Samos and a year later it consisted of five different photographic payloads and two electronic intelligence payloads. Despite this growth, the Samos project office did not begin a weather satellite, and none of the cameras then under development would have been useful for providing cloud photography, primarily because they all photographed small areas of the earth rather than the vast areas covered by weather patterns.[13]

KC-135 tankers refueling a B-47 medium bomber and a B-52 Stratofortress. Weather reconnaissance was vital to planning successful refueling operations, and the Air Force had B-47s dedicated to collecting weather data. Despite the requirement and the existing cost of weather reconnaissance operations, the Air Force was slow to embrace the idea of a weather satellite to gather that data. (credit: USAF via Robert Hopkins III) |

Cloud reconnaissance

In late March 1959, Amrom Katz wrote a draft recommendation that the Air Force develop its own “cloud reconnaissance satellite.” In his summary he explained that “peculiar are requirements, close tie-in to classified and sensitive operations, and above all, requirements for timely data, all point to a system controlled and operated by USAF.”[14]

| What changed things was the October 1957 launch of Sputnik. Suddenly WS-117L was force-fed with money by the Air Force leadership |

Katz turned his attention to the need to supply weather information to the military services. “By and large, the example of the Pentagon notwithstanding,” Katz wrote, “these services work outdoors, where there is nothing but weather, which sometimes aids the services' work, sometimes hinders it.”[15] The Air Force needed timely weather data to support several missions. One high-priority mission was aerial refueling Strategic Air Command bombers. Aerial refueling requires that the pilots be able to see the tanker aircraft, which they cannot do in heavy clouds. A satellite could allow planners to pick good areas for the planes to rendezvous, a job that was complicated by the fact that the Air Force’s two different fleets of tanker aircraft operated at different altitudes with different weather conditions. In addition, a satellite might allow for planning nuclear bombing missions, because many aircraft designated to carry nuclear bombs had to rely upon visual location of their target.[16] Another important contribution of such a satellite would be for planning airborne reconnaissance missions. Many airborne reconnaissance sensors are “weatherÂlimited,” and such missions are both expensive and potentially dangerous. “It is a waste of an already meagre effort to take pictures of clouds on these missions,” Katz explained.

An additional mission was programming reconnaissance satellites. The Samos readout satellites scheduled to enter operation in two years would transmit their images to the ground over a 6-megahertz radio link, which was not much. Katz noted that the camera could theoretically photograph an area 36 to 40 times greater than its ability to transmit to the ground. “We envision the cloud recce satellite as an intimate partner of this long focal length video talk-back satellite,” Katz wrote. “A kind of cloud-spotter that says, ‘not now, Jack, save yourself for the next orbit.’”[17]

The final mission for such a weather satellite was providing information on clouds for recoverable reconnaissance satellites. They not only had the same need for cloud-free photography as the Samos readout satellites, but recovery operations to retrieve the satellite after re-entry also depended upon accurate weather information.[18] Katz then proposed a relatively simple modification to the existing Samos reconnaissance satellite to produce cloud photographs of larger areas. Several other modifications would be required, but Katz felt that the system could provide useful data at minimal cost and development time.[19]

Katz's proposal was soon followed by a second RAND study in April 1959 by one of his colleagues who argued that instead of using a film-scanning system, the weather satellite should use a television system.[20] By this time, a weather satellite using a television system was already underway, but the Air Force did not control it. Another military service did.[21]

Next: In part 2, the Air Force gets its weather satellite, and loses it.

References

- Thomas S. Blanton, “They Spy, But Why?” Newsday, Sunday, March 11, 2001, p. 5.

- Douglas Aircraft Co, “Preliminary Design of an Experimental World-Circling Spaceship,” Report No. SM-11827, May 2, 1946, contained in: John M. Logsdon, et. al., eds. Exploring the Unknown, Vol. I (NASA, SP-4407, 1996), pp. 236-244.

- S.M. Greenfield and W.W. Kellogg, “Inquiry Into the Feasibility of Weather Reconnaissance From a Satellite Vehicle,” R-218, The RAND Corporation, April 1951.

- Ibid., p. v.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 2.

- Ibid., p. la.

- Ibid., p. 13.

- For more information on the early reconnaissance satellite development, see Dwayne A. Day et al, Eye in the Sky (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998); see also James S. Coolbaugh, “Genesis of the USAF's First Satellite Program,” Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, August 1998, pp. 283-308.

- W.R. Cartheuser, “Weather Degradation of Reconnaissance,” D-4003, The RAND Corporation, December 10, 1956.

- Radio Corp of America, “Outline of a Development Plan for an Advanced (Satellite) Reconnaissance System for United States Air Force,” February 29, 1956; Martin Co., “Advanced Reconnaissance System,” January 15, 1956. (Originals at Defense Technical Information Center.) Both RCA and Martin lost the contract to build the WS-117L Advanced Reconnaissance System in January 1956, but these reports undoubtedly represent their bids for the contract.

- This is based upon conversations with several of the original WS-117L officers, who have said that simply getting enough money to pay for the reconnaissance mission was difficult. They could not bother with other missions like meteorology.

- See Eye in the Sky for further details.

- Amrom H. Katz. “An Air Force Weather Satellite - Why and How,” SOFS- STRATRECCE-1, The RAND Corporation, March 31, 1959, p. ii.

- Ibid., p. 4.

- Ibid., pp. 5-6.

- Ibid., pp. 6-7.

- Ibid., p. 7. Katz's mention of recoverable reconnaissance satellites in this document is notable. Katz and his colleague Merton Davies had proposed such a satellite in 1957. After it was formally started, they were told that it had been cancelled and were not allowed to know of its existence. However, by early 1959, Katz started to suspect the truth, that a covert project was underway under the disguise of the Discoverer program. His comments in classified documents like this one on the weather satellite quickly made many people nervous, and eventually Katz was questioned about what he knew of the CORONA program. He was then informed of its existence and after that had to stop mentioning the project outside of formal channels.

- Ibid., pp. 8-12. Katz apparently also described this system in a separate report, RAND D-6243, around the same time.

- J.H. Huntzicker, “An Air Force Weather Satellite Utilizing T-V,” D-6252, The RAND Corporation, April 6, 1959. This document references RAND D-6243.

- John H. Ashby, “A Preliminary History of the Evolution of the Tiros Weather Satellite Program, (HHN-45),” NASA, Goddard Space Flight Center, August 1964, NASA History Division.

Dwayne Day can be reached at zirconic1@cox.net.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

The Launch Market Squeeze

A Soyuz rocket launches a batch of OneWeb satellites in late 2021. With Soyuz no longer available, OneWeb has had to turn to a competitor, SpaceX, to launch its satellites. (credit: Arianespace) |

The launch market squeeze

by Jeff Foust

Monday, March 28, 2022

If politics makes strange bedfellows, then geopolitics makes strange business relationships, as OneWeb and SpaceX revealed last week.

In a move that was both shocking and predictable, OneWeb announced last Monday that it had signed an agreement to launch some of its satellites on SpaceX rockets. Shocking, because the two companies are archrivals in the broadband satellite megaconstellation market, working as fast as they can to deploy their satellites and offer service globally. Predictable, because OneWeb had few, if any, other options for deploying the rest of its fleet when it suspended use of the Soyuz rocket after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine a month earlier.

“We thank SpaceX for their support, which reflects our shared vision for the boundless potential of space,” Neil Masterson, CEO of OneWeb, said in a statement. “With these launch plans in place, we’re on track to finish building out our full fleet of satellites and deliver robust, fast, secure connectivity around the globe.”

| “We’re delighted that SpaceX certainly stepped up and we appreciate that,” said OneWeb’s Masterson. |

OneWeb offered no other details about its launch agreement with SpaceX, including the number of launches or the cost, other than the first launch “is anticipated in 2022.” OneWeb had six more Soyuz launches, each carrying about three dozen satellites, remaining to complete its constellation when it suspended its launch plans. That came after Russia made demands that OneWeb’s satellites not be used for military purposes and that the British government divest its stake in the company. A set of satellites remains stuck at the Baikonur Cosmodrome after its launch was called off in early March.

“We were caught essentially in a geopolitical situation,” Masterson said on a panel at the Satellite 2022 conference in Washington a day after this company announced its agreement with SpaceX. “We’re delighted that SpaceX certainly stepped up and we appreciate that.”

He dodged questions about the specifics of the contract, though, as did another executive on the sidelines of the conference, who only said that OneWeb was in talks with other launch providers as well.

OneWeb is not alone in struggling to find alternative launches because of the effective withdrawal of the Soyuz from the global launch market. When Russia announced it would no longer conduct Soyuz launches from French Guiana, it stranded five European government missions: two launches of pairs of Galileo navigation satellites, ESA’s Euclid astronomy mission and EarthCARE Earth science mission, and a French military reconnaissance satellite.

At a press briefing after a meeting of the ESA Council March 17, agency leaders said they had not made any decisions about how to launch those stranded payloads. “We will look into all the options,” said Josef Aschbacher, ESA’s director general. “We need to make sure that we have a robust launcher setup that can launch our satellites.”

ESA is also looking into a new launch for its ExoMars mission, which was to launch in September on a Proton. ESA announced at that council meeting that it was suspending cooperation with Roscosmos on ExoMars, requiring the agency to find not just a new launch but also replace other Russian components, including the landing platform that would have delivered ESA’s Rosalind Franklin rover to the surface and instruments on the rover itself.

That will delay the mission by at least four years. “It will not be before 2026, realistically,” Aschbacher said of the revised ExoMars launch date. “Even that is very challenging.”

The challenge facing ESA and OneWeb and a handful of other Soyuz customers, like the European weather satellite agency Eumetsat and the South Korean government, is that there is little available launch capacity globally among larger launch vehicles. Despite all the handwringing about a glut of small launchers, there is precious little capacity to support new customers with the withdrawal of Russian launch vehicles and continued exclusion of Chinese vehicles for Western satellites.

| “We’re very pleased with where the BE-4 is and we expect to fly this year as a result,” Bruno said. |

That capacity crunch comes from a delayed transition to a new generation of launch vehicles (see “New year, new (and overdue) rockets”, The Space Review, January 10, 2022). Four new large launch vehicles were expected to be in service by now—Ariane 6, H3, New Glenn, and Vulcan Centaur—but none of those vehicles have made an inaugural launch.

At a Satellite 2022 panel last week, Tory Bruno, CEO of United Launch Alliance, said Vulcan was still on track for a first launch later this year. The schedule of that vehicle has been paced by the development and testing of Blue Origin’s BE-4 engine that will power Vulcan’s first stage.

Bruno said he expected to receive the first flight models of the BE-4 engine by the middle of the year. “We’re very pleased with where the BE-4 is and we expect to fly this year as a result,” he said.

The engine is still undergoing testing, including a series of firings at Blue Origin’s West Texas test site that also hosts New Shepard launches. Jarrett Jones, senior vice president of New Glenn at Blue Origin, said during the panel that the company had recorded more than 18,000 seconds of run time on the BE-4 as final qualification tests of the engine nears.

Despite the extensive delays in the engine, Bruno said he was satisfied with the engine itself. “The engine is in great shape,” he said. “It is performing better than I anticipated.”

ULA is still flying the Atlas 5, which is not affected by Russian sanctions: the company secured all the RD-180 engines it needs for its remaining missions. The problem, though, is that all of those missions are sold to government and commercial customers, meaning ULA can’t offer the Atlas 5 to others now looking for alternative access to space. The company declined to bid on the launch of the GOES-U weather satellite last year even though it won contracts for its three predecessors, GOES-R, -S, and -T, because of a lack of available vehicles; GOES-U will instead launch on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy.

Arianespace, which marketed the Soyuz to customers like OneWeb in addition to Europe’s own Ariane and Vega rockets, is working to adjust to the new reality. “2022 will be very different for us from what we were supposed to do,” Arianespace CEO Stéphane Israël said on the panel. “We are working very closely with our customers to accommodate the best solutions for them.”

He did not discuss what the company is doing with OneWeb, but said he hopes to shift the stranded European institutional payloads to Ariane 6 and Vega C, two new rockets scheduled to make their first flights this year. He particularly suggested that Ariane 6 could launch the Galileo satellites in 2023. “Ariane 6 has been designed to launch Galileo satellites,” he said. “Ariane 6 can launch these satellites in 2023.”

ESA officials have also expressed their desire to launch European payloads on European vehicles, but have not announced any decisions yet. While Vega C is expected to make its inaugural launch in May, ESA has yet to set a date for the first Ariane 6 launch, preferring to wait until the vehicle completes tests this spring.

The agency has at least left the door open for using the first Ariane 6 launch, currently slated to carry a mass demonstrator and a handful of rideshare payloads, for one of the missions that was to fly on Soyuz. “It’s not the baseline, to be clear, to use this launch for one of the payloads,” said Daniel Neuenschwander, ESA’s director of space transportation, at the briefing after the ESA Council meeting. “But, we are assessing it and we will come back with a clear assessment and a proposal to our member states.”

Use of the Vega C is complicated by the fact that the rocket’s fourth stage uses the RD-843 engine produced by Ukrainian company Yuzhmash. Neuenschwander said that there are three such engines in storage in Europe for use on the Vega C launches planned for this year, and that ESA was looking at options to replace that engine if needed for later missions. Avio, the prime contractor for Vega, said in a statement Friday there were no issues for Vega launches for the “medium term” but declined to disclose how many engines it had available.

That engine will ultimately be replaced by M10, a methane-liquid oxygen engine under devleopment in Europe, for the Vega E around the middle of the decade. Israël said there was “no need” to accelerate work on that engine, and that “backup solutions in Europe” could replace the RD-843 if required.

| “I look at them as my friend that I can talk to and bump off as needed,” SpaceX’s Ochinero said of Starlink. |

The Japanese space agency JAXA and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries have said little recently about progress on the H3. It has been delayed by ongoing problems with the new main engine for the vehicle, putting a debut this year in doubt. The H-2A is headed for retirement with few, if any, vehicles available for other customers.

Blue Origin, meanwhile, has acknowledged that New Glenn won’t make its debut this year. Jones, speaking at the Satellite 2022 panel, said that qualification of various elements of the vehicle is ongoing, it had run out of runway to be ready in time for an inaugural launch in 2022.

He declined to give a new target for a first launch because the company was still in discussions with customers about the revised schedule. “It will not be at the end of this year,” he said.

That leaves SpaceX as the only launch provided with room to accommodate additional customers like OneWeb. Tom Ochinero, vice president of commercial sales at SpaceX, declined to say exactly how much room it has in its manifest for additional launches, saying it maintains a “more fluid and flexible” approach to managing its upcoming launches.

Part of that flexibility, he said, comes from having “reserve slots” on the manifest as well as changes caused when other customers need to reschedule their launches because of delays with their payloads. Another part comes from the fact that the biggest Falcon 9 customer is SpaceX itself, through its Starlink launches.

“I look at them as my friend that I can talk to and bump off as needed,” he said of Starlink. “They can move or give up their vehicles. I’ve got a lot of flexibility there.”

This constraint in supply of larger launch vehicles is short-lived. Within the next couple of years, the Ariane 6, H3, New Glenn, and Vulcan should all be flying—not to mention, of course, SpaceX’s own Starship, which together could turn a shortage of vehicles into a glut.

Others are developing vehicles that could fill in the niche abandoned by the Soyuz in the medium-class market, like Firefly’s Beta, Relativity’s Terran R, and Rocket Lab’s Neutron, which are slated to enter service as soon as mid-decade. “It will accelerate our look at the entire marketplace,” Jason Mello, president of Firefly Space Transportation Services, said of the withdrawal of Soyuz during a separate Satellite 2022 panel.

In the meantime, though, anyone needing a launch soon who hadn’t already booked a ride may have just one place to go, provided SpaceX is willing to bump another Starlink launch or two.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you