Since I was a young child Mars held a special fascination for me. It was so close and yet so faraway. I have never doubted that it once had advanced life and still has remnants of that life now. I am a dedicated member of the Mars Society,Norcal Mars Society National Space Society, Planetary Society, And the SETI Institute. I am a supporter of Explore Mars, Inc. I'm a great admirer of Elon Musk and SpaceX. I have a strong feeling that Space X will send a human to Mars first.

Thursday, September 29, 2022

Wednesday, September 28, 2022

The Orbits Of Life

The Orbits of Life

Earth can become more habitable for life as long as Jupiter changes its orbit around the Sun, Space.com reported.

In a new paper, astronomers at the University of California-Riverside simulated different arrangements of the solar system and came across some interesting findings.

They explained that a planet’s proximity to its star affects how much radiation it absorbs and its internal climate. They added that planets with more circular orbits maintain a steady distance from their star. Meanwhile, eccentric orbits – or oval-shaped – bring the celestial bodies closer or further away from their stars at different points.

The team noted that if Jupiter had a more eccentric orbit, it would also influence the Earth’s orbit, making it more oval.

This would mean that the Earth would periodically get closer to the Sun than it already gets. Consequently, frozen areas of the planet would become warmer and reach temperatures of the hospitable range – somewhere between 32 and 212 degrees Fahrenheit.

But researchers also observed that the ability to hold life is also impacted by a planet’s tilt, which influences how much radiation it receives from a star.

In case Jupiter decides to get a little closer to the Sun, it would cause extreme tilting in our world and less sunlight – meaning that a large part of the planet would be frozen.

The authors said that the findings could help astronomers better detect habitable planets outside the solar system.

Tuesday, September 27, 2022

An Analysis Of Chinese Remote Sensing Satellites

A Long March 2D rocket launched a Yunhai-1 military weather satellite September 21. (credit: Xinhua) |

An analysis of Chinese remote sensing satellites

by Henk H.F. Smid

Monday, September 26, 2022

As was to be expected, the answer from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to the political visit of US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and a Democratic congressional delegation to Taiwan in August was in the form of threatening military operations and drills executed against Taiwan. The maneuvers took place in the waters and skies near Taiwan and included the live-firing of ballistic missiles in the Taiwan Strait. Undoubtedly, the use of the formidable Chinese satellite remote sensing assets made clear to the American military involved that the ability to deploy warships or aircraft with impunity, and even to operate safely from bases in the region, was no longer the case as it was during the mid-1990s. At that time a crisis erupted over Taiwan’s president visiting the US, prompting an angry reaction from Beijing. Reacting, the US Navy sent warships through the Taiwan Strait and there was nothing the PRC could do about it. Now, the USS Ronald Reagan aircraft carrier group just remained in the region to “monitor the situation.” The greatly improved Chinese satellite surveillance capabilities and inherent intelligence of the last two decades made the difference for the most part.

The following is a non-exhaustive overview of the development and current execution of China’s satel lite surveillance capabilities. From 2015 on, commercial satellite Earth observation plays an important role too. Since remote sensing (data) from satellites is dual-use, there is no clear distinction between civil and military satellite surveillance, but for the sake of clarity it will be maintained. Only satellites will be covered, ground application systems and infrastructure will not be considered here.

Satellite remote sensing is defined here as the use of satellite sensors to observe, measure and record electromagnetic radiation reflected or emitted by the Earth and its surroundings for subsequent analysis and extraction of information. In addition, all remote sensing (data) from satellites is considered dual-use.

Civil remote sensing satellites

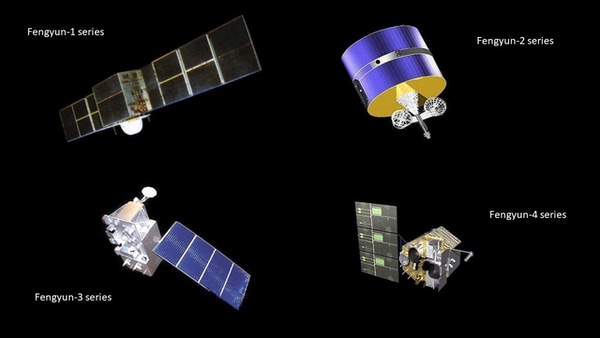

Fengyun meteorological satellite (FY)

Fengyun is a meteorological satellite series managed by the China Meteorological Administration. Within the meteorological program, the odd-numbered satellites (FY 1, FY 3) refer to polar-orbiting low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites, while the even-numbered satellites are geostationary Earth orbit (GEO) satellites (FY 2, FY 4). The FY 1 satellite series was China’s first generation of polar-orbiting meteorological satellites. Its main task was to obtain atmospheric, cloud, land, and ocean information at home and abroad, and to collect relevant data for weather forecasting, climate prediction, natural disasters and global environmental monitoring. FY 1 and FY 2 started and improved China’s weather forecast capabilities over time. Second generation satellites became operational in 2008 (LEO FY 3) and 2016 (GEO FY 4). All Fengyun satellite data products are available to users all over the world and can be downloaded for free. Fengyun satellites are included in the world’s global operational meteorological satellite series of the World Meteorological Organization.

Four types of Fengyun meteorological satellites. (credit: CMA/SCS) |

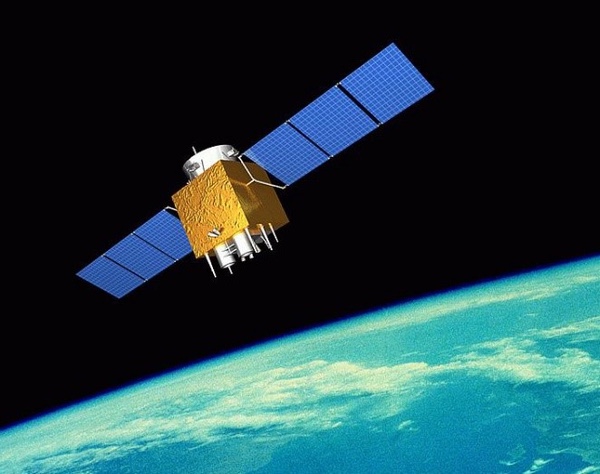

Haiyang Ocean Satellite (HY)

Haiyang are a group of marine scientific remote sensing satellites developed by Chinese Academy of Space Technology (CAST) and operated by the National Satellite Ocean Application Service, a subordinate agency of the State Oceanic Administration. The spacecraft use the three-axis stabilized CAST968 platform. The HY 1 series [2002, 2007, 2018, 2020] is China’s first satellite for surveying ocean resources (ocean color and sea surface temperature) and monitoring the environment. The HY 2 series [2011, 2018, 2020, 2021], is a parallel series to HY 1. HY 2 monitors the dynamic ocean environment with microwave sensors. It detects sea surface wind field, sea surface height, and sea surface temperature. Sensors are an altimeter, a scatterometer, and a microwave imager. HY 3 satellites, still to be launched, will be used to monitor islands, coastal zones, and maritime targets to obtain ocean geodesy information with optical, infrared and microwave sensors.

Haiyang 1 marine scientific remote sensing satellite. (credit: NSOAS) |

Haiyang 2 research of dynamic ocean environment. (credit: CAST) |

Huanjing Disaster and Environmental Monitoring Satellite (HJ)

China plans to launch a total of 11 Huanjing satellites for disaster and environmental monitoring. The satellites will have visible, infrared, and multi-spectral sensors, and synthetic aperture radar (SAR). Up until now, five satellites have been launched. The first two satellites, HJ 1A/B, were launched simultaneously in 2008 in a coplanar orbit with a phasing of 180 degrees and were optical imaging satellites. HJ 1C, that was launched in 2012, is the first civilian Chinese remote sensing satellite to use a SAR radar. This S-band SAR was manufactured in Russia by NPO Mashinostroyeniya. In 2020, HJ 2A/B were launched and probably are improved satellites that will replace HJ 1A/B.

Huanjing 1 Disaster and Environmental Monitoring Satellite. (credit: CAST) |

Ziyuan/CBERS Earth Resources Satellite (ZY)

The Ziyuan I/CBERS program integrated a 1970s plan to develop Brazilian and Chinese economies through major projects by promoting the use of space. Ziyuan I/CBERS satellites were designed for global coverage and include optical cameras and a system for collecting data on the environment. They are jointly managed by the PRC and Brazil. From 1999 to 2019, four successful CBERS missions were flown; three more ZY missions were launched in which China did not cooperate with Brazil.

Ziyuan II was billed as a civilian Earth observation system, but was militarily codenamed Jianbing-3 and was China’s first [2000] military high-resolution digital remote sensing satellite. They are reportedly used for area surveillance.

Ziyuan III is China’s first high-resolution civilian stereoscopic Earth observation program and has the overall goal of creating large-scale, three-dimensional maps and “providing relevant parameters for environmental monitoring, resource management, disaster response, urban planning and national security”.

CBERS-4 or Ziyuan I-04 Earth resources satellite. (credit: INPE) |

Ziyuan II Earth resources satellite. (credit: CAST) |

China High-resolution Earth Observation System (CHEOS)

In 2006, CHEOS was established as one of sixteen major national science and technology projects. Proposed was to build a high-resolution Earth observation system based on satellites, stratospheric airships, and aircraft. The associated ground systems would be improved or developed. The combination of these measures had to provide an all-weather, all-time, and global Earth observation capability. CHEOS therefore, should have multi-observation capabilities to provide high spatial-, temporal- and spectral resolution properties. From 2013 on, Gaofen satellites were launched to create the satellite-based part of CHEOS.

Gaofen [high resolution] Earth observation satellite (GF)

For the CHEOS program, more than 25 Gaofen satellites have been launched since 2013. These satellites are based on CAST satellite busses. It is known from the first seven GF series that different sensors are often used on each satellite. For example, GF 1, 2, 4, and 6 have high-resolution cameras and GF 3 is equipped with a C-band SAR. GF 5 has six sensors, including a hyperspectral camera and a directional polarization camera. The extra laser altimeter system on GF 7 enables three-dimensional research. Resolution capabilities and other information about Gaofen satellites was published for the lower numbered Gaofen series of satellites. Information for Gaofen satellites with number 8 and higher has not been publicly released, suggesting that the satellites are (partly) for national defense purposes.

Deployed GF 1 spacecraft. (credit: www.cheos.org.cn) |

Deployed GF 1 spacecraft. (credit: www.cheos.org.cn) |

Gaofen satellites [SCS, August 1, 2022]

| Satellite | Year of Launch | Function/Sensors |

|---|---|---|

| Gaofen 1 series | 2013, 2018 | 2 HR (2m Pan, 8m MS) and 4 WFV (16m MS) camera’s |

| Gaofen 2 | 2014 | 2 Identical cameras with 0.8m Pan, 3.2m MS |

| Gaofen 3 series | 2016, 2021, 2022 | High Resolution SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar) |

| Gaofen 4 | 2015 | HR camera’s in geostationary orbit |

| Gaofen 5 series | 2018, 2021 | 6 Different sensors for atmospheric observations |

| Gaofen 6 | 2018 | Multispectral sensors with high spatial resolution |

| Gaofen 7 | 2019 | 2 High resolution camera’s with a coupled laser altimeter |

| Gaofen 8 | 2015 | High resolution optical imaging payload |

| Gaofen 9 series | 2015, 2020 (4) | High resolution payload for urban planning |

| Gaofen 10 | 2016, 2019 | Unknown |

| Gaofen 11 series | 2018, 2020, 2021 | Optical camera’s with high spatial resolution, military? |

| Gaofen 12 series | 2019, 2021, 2022 | High Resolution SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar) |

| Gaofen 13 | 2020 | HR camera’s in geostationary orbit |

| Gaofen 14 | 2020 | Electro-optical stereo cartography |

| Gaofen DUOMO | 2020 | Optical payload with sub-meter resolution |

Commercial remote sensing satellites

Beijing series of commercial optical remote sensing satellites

Beijing 1 [2005] and constellation satellites Beijing 2 [2015, 2018] were commercially built for China by Surrey Satellite (UK). Noteworthy, the imaging capacity of Beijing 2 was 100% leased by a Singapore based company. Beijing 3 [2021, 2022] satellites have been built by China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation to acquire optical remote sensing satellite data and information products for the global commercial market. Beijing 3 satellites will mainly be used to provide remote sensing services in the fields of land resources management, agricultural resources survey, environment monitoring and city applications.

Beijing 3 commercial optical remote sensing satellite. (credit: China-Arms.com) |

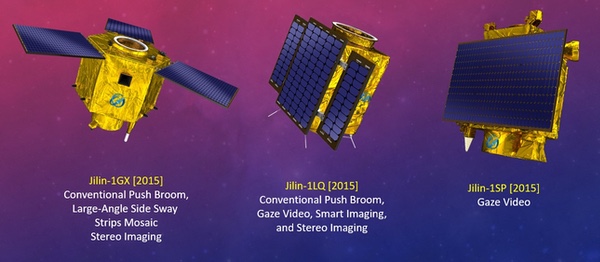

Jilin-1 series of satellites

Jilin-1 is China’s first, self-developed, commercial remote sensing satellite system and is operated by the Chang Guang Satellite Technology Corporation (CGSTC). The Jilin-1 satellite constellation is the core project and will eventually be composed of 138 remote sensing satellites covering high resolution, large swath width, video, and multi-spectrum, and a high revisit commercial service. As of the beginning of September, CGSTC has successfully launched 73 Jilin-1 satellites into space. The completed Jilin-1 constellation will be able to visit any place in the world 15 to 17 times per day, with the ability to update a global map every year and a national map five times per year. It can provide “high-quality remote sensing information and product services for agricultural and forestry production, environmental monitoring, smart city, geographical mapping, land planning and other fields”.

1st Generation Jilin-1 remote sensing satellites. (credit: CGSTC/SCS) |

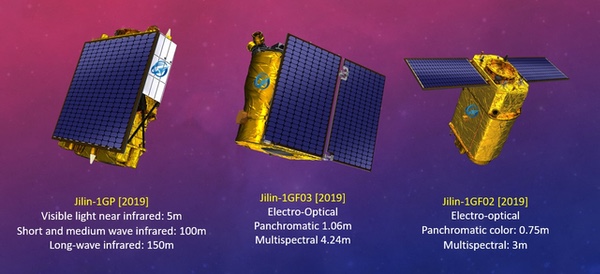

The first generation of Jilin-1 satellites were put in orbit in 2015, the second generation in 2019. A batch of eight Jilin-1 satellites (one Wideband 01C and seven Gaofen 03D spacecraft) were put in orbit on May 5, 2022. The Wideband 01C satellite is a 230-kilogram spacecraft featuring a high resolution video capability. The payload provides a 0.5-meterresolution optical as well as a 2-meter resolution multi-spectral capability. The seven 40-kilogram Gaofen 03D high-resolution imaging satellites in this launch provide better than a 0.75-meter resolution optical as well as a 2-meter resolution multi-spectral capability. The last batch, August 10, 2022, consisted of 16 Jilin-1 imaging satellites: ten in the Jilin-1 Gaofen high resolution optical imaging series and the first six in the Jilin-1 Hongwai A (infrared imaging) series.

2nd Generation Jilin-1 remote sensing satellites. (credit: CGSTC/SCS) |

Comprehensive information on Jilin-1 satellites can be obtained from the CGSTC website.

Military remote sensing satellites

Yunhai meteorological satellite (YH)

Yunhai 1 is a meteorological satellite series [2016, 2019] in Sun-synchronous orbits (SSO), according to state media used for “detecting the atmospheric and marine environment and space environment, as well as disaster control and other scientific experiments.” The Yunhai series are assessed to have military purposes. Yunhai 1 satellites have been built by the Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology, possibly based on the CAST2000 platform. Data provided by the Yunhai 1 satellites complement the information provided by the civil Fengyun meteorological satellites. Yunhai 1-02 [2019] suffered a breakup event on March 18, 2021, probably after an accidental collision with space debris.

Yunhai 2 is a constellation of military meteorological satellites. The satellites reportedly use Global Navigation Satellite System radio occultation to collect atmospheric data for weather forecasting and for ionosphere, climate, and gravity research. A first cluster of six identical Yunhai 2 satellites was launched in December 2018 in an 800-kilometer circular orbit at 50 degrees inclination together with a Hongyan 1 prototype communications satellite.

Ludi Kancha Weixing (LKW)

Ludi Kancha Weixing is a high-resolution optical Earth observation satellite for military purposes. Chinese media have stated that the satellites are used for remote sensing exploration of land resources. However, the secrecy surrounding the satellites is extreme, even by Chinese standards, giving credence to the theory that they are part of the country’s military topographical (the name means Land Survey Satellite) reconnaissance efforts. Looking at its parameters, the LKW satellites appear to be connected to the Yaogan reconnaissance satellite fleet. Based on its appearance—a hexagonal satellite body with three radial fixed solar panels—the satellite is likely suitable for hosting a telescope of about 65 centimeters and thus, in a 500-kilometer orbit, achieving a possible ground resolution of up to 0.7 meters for panchromatic and better than 3 meters for multispectral and near-infrared images. In 2017 and 2018, two satellites were launched into space. The rapid deployment pace of these four satellites are previously only seen in military-operated satellite projects.

Ludi Kancha Weixing Land Survey Satellite. (credit: CCTV) |

Tianhui Yi Hao Weixing

Tianhui is a collective name for a network of several topographical satellites, built by Dong Feng Hong and operated by the People’s Liberation Army. It includes Earth observation missions using optical, radar, gravity, and magnetism sensors to obtain geo-information about the Earth. The program provides for the launch of nine satellites of six different types to obtain quantitative research of the Earth’s land, sea, gravity and magnetic field. These satellites will form a space-based Earth observation network to conduct both basic Earth survey and detailed survey for key areas or in response to an emergency.

Tianhui 1 satellites are part of the Ziyuan program which includes several civilian and military remote sensing programs. Four satellites of this type have been launched (2010–2021) in 500-kilometer SSO. The satellites are equipped with two different camera systems. One of them in the visible range (5 meters resolution), and the other in the infrared band (10 meters resolution).

Tianhui 1 topographical satellite. (credit: CAST) |

Tianhui 2 satellites will be used, according to state media, to conduct land surveys, mapping, and scientific experiments in space. The Tianhui 2 series is the first microwave measurement system for China to use interferometric synthetic diaphragm radar (InSAR) technology, working together in pairs. (The satellite system is probably similar to the German TanDEM-X satellite system.) The Tianhui 2 satellites are believed to operate in the X-band and have a resolution of 3 meters. The first group of two satellites was launched in 2019. The mission was not announced in advance by China and NOTAM’s for the launch were not sent. The pair of Tianhui 2 satellites have been launched in almost the same type of orbit, 500-kilometer SSO, as the four Tianhui 1 satellites.

There is no Tianhui 3 satellite as of now. The Tianhui 4 satellite (2021) will, reportedly, observe the Earth in both the visible and infrared spectrum using two cameras with a resolution of less than 5 meters. It has been built by the Dong Feng Hong Corporation/CAST and is operated by the People’s Liberation Army.

Possible Tianhui 2 topographical satellites. (credit: CCTV-4) |

Tongxin Jishu Shiyan Weixing (TJS)

Tongxin Jishu Shiyan (Weixing) are a series of Chinese satellites that have been deployed in geostationary orbit since 2015 and presented by Chinese authorities as telecommunications satellites. Specific features have not been published and the real purpose of each satellite is therefore questionable. The behaviors exhibited by these satellites indicate a mixture of applications though. All TJS satellites are in geostationary orbit (GEO). Some appear to be built for missile warning (built by the Shanghai Institute of Satellite Engineering), while others seem to operate like signal intelligence satellites (built by CAST, a Beijing based satellite factory). According to the Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology, TJS 6 and TJS 7 have experimental docking stations. In any case, by Western observers they are considered to be military satellites because of the limited information available and the lack of published outcomes. It cannot be said with any certainty what kind of (military) satellites the launched TJS 3 and TJS 7 (2018, 2021) are. There seems to be no TJS 8.

TJS 1, 4, and 9 (2015, 2019, 2021) are assessed to be electronic intelligence (ELINT) satellites. They are sometimes also referred to as Qianshao-3 or Chang Cheng. Reportedly, TJS 1 had successfully deployed China’s first large aperture reflector antenna (about 32 meters across) after it reached GEO.

TJS 2, 5, and 6 (2017, 2020, 2021) are assessed to be early warning of ballistic missiles satellites. They are sometimes also referred to as Huoyan. The name Huoyan means Fire Eyes that may suggest infrared sensors.

TJS 4 Probable ELINT satellite (Reflector not deployed). (credit: CCTV) |

TJS 5 Probable Early Warning satellite. (credit: SAST) |

Jianbing Military Remote Sensing Satellites

Chinese military reconnaissance satellites are usually categorized based on their military Jianbing (group) designation. The first Jianbing group were the first generation of Fanhui Shi Weixing photo reconnaissance satellites (1975). The first Yaogan satellite, as most military remote sensing satellites have been publicly called since 2006, was the first of the Jianbing 5 group. Since 2015, the Jianbing-Yaogan relationship is no longer very clear and Western analysts differ on this naming. Yaogan satellites primarily support the People’s Liberation Army and may support civil causes too. They utilize various means of remote sensing: synthetic aperture radar (SAR), electro-optical reconnaissance (EO), and electronic intelligence (ELINT) for ocean surveillance.

Fanhui Shi Weixing (FSW)

The Fanhui Shi Weixing (FSW) satellite program was conceived and developed in the late 1960s. From 1975 to 1996 there were some 17 launches and salvages of three generations FSW satellites (military designation Jianbing 1). Military reconnaissance was done using photographic film, from a prism-like panorama camera, which, after salvaging the photo capsule, was developed on Earth. Under the Jianbing 2 and 4 name, six more, improved, FSW satellites were launched (2003–2005). The Jianbing 3 name was reserved for the three Ziyuan 2 Earth observation satellites (2000–2004). The FSW program is assessed to be terminated.

Fanhui Shi Weixing 3 Satellite. (credit: CAST) |

Yaogan | Jianbing – synthetic aperture radar (SAR)

Jianbing 5 was the first generation of synthetic aperture radar (SAR) reconnaissance satellitea. The satellite (2,700 kilograms) was equipped with an L-band SAR system with two working modes with 5 meters and 20 meters resolution respectively. The satellite operated in a polar orbit of 630 kilometers at an inclination of 98 degrees. In total, three missions of this series have been launched (see table).

Jianbing 7 is believed to be a second-generation radar reconnaissance satellite. Operating from a polar orbit of 510 kilometers at an inclination of 97.4 degrees, the satellite is equipped with a SAR package that offers a spatial resolution of about 1.5 meters. Since 2009, a total of four missions have been launched.

Jianbing 5 L-band SAR reconnaissance satellite. (credit: astronautix.com) |

Jianbing 7 SAR reconnaissance satellite. (credit: CCTV) |

Jianbing X is believed to be a new type of SAR reconnaissance satellite. Yaogan 29, 33, and 33R are associated with this name. Yaogan 29 (2015), operating from a polar orbit of 615 kilometers at 97.3 degrees, the satellite is equipped with a SAR package that may offer a spatial resolution of better than 1.5 meters. It is possibly an improved Jianbing 5. Some analysts refer to this satellite as Jianbing 12.

Yaogan 33 [2019] was believed to be the second Jianbing X launch, but it failed. Yaogan 33R (2020) was initially seen as a replacement for Yaogan 33, but used a different launch site and a higher orbit: 682 kilometers at 98.7 degrees. There is a lot of ambiguity and confusion between analysts. Reportedly, 33R is not related to 33, but the name would have been reused. Either way, the satellite payload is believed to be a radar satellite of a new series, but details are unclear for now.

Yaogan | Jianbing – Electro-optical

The Jianbing 6 group consists of electro-optical reconnaissance satellites. The satellite is three-axis stabilized, with track maneuvering ability. Operating from a 630-kilometer SSO, the satellite is able to capture images of the Earth with a spatial resolution of about 1.5 meters. The satellite has an X-band data link for sending image data to dedicated ground stations. A total of six missions have been launched so far. Jianbing 10 is a second-generation electro-optical reconnaissance satellite developed using the Phoenix Eye satellite bus. This versatile bus is designed for SSO and has also been used in the Ziyuan 2 and CBERS Earth observation satellites programs. The optical payload has a spatial resolution of 0.77 meters. A total of three missions have been launched.

Jianbing 6 military surveillance satellite. (credit: CAST) |

Jianbing 10 military surveillance satellite. (credit: CCTV) |

Jianbing 9 is believed to be the third generation of electro-optical reconnaissance satellites. The satellite’s imaging package was developed by the Changchun Institute of Optics. The satellite operates at a much higher altitude than previous Chinese electro-optical satellites, at a 1,200-kilometer orbit with an inclination of 100.3 degrees. Since 2009, a total of five missions have been launched.

Jianbing 11 is a high-resolution electro-optical reconnaissance satellite, possibly the successor to the Jianbing 10 group of satellites (fourth generation). Operating from a 490-kilometer SSO, it is believed that the satellite is capable of delivering images with a resolution of less than one meter. Since 2012, two satellite missions have been launched.

Jianbing 9 military surveillance satellite. (credit: CCTV) |

Jianbing 11 military surveillance satellite. (credit: CCTV) |

According to the website China.org, the Yaogan 26 satellite will be used as a new remote sensing device for scientific experiments, land surveys, crop yield assessments, and disaster monitoring. However, analysts believe that this class of satellites is used for military purposes. Developed by CAST and based on the Phoenix Eye-2 platform, the satellite is likely capable of high-resolution observation and also carries an infrared sensor. Western analysts differ widely on the name combination this satellite should have.

Yaogan 26 military surveillance satellite. (credit: CCTV) |

Yaogan | Jianbing – Ocean Surveillance

One of the main objectives of the Jianbing Ocean Surveillance program is to put an end to the near invulnerability of US aircraft carriers. An aircraft carrier and its associated naval air group are extremely well defended. They are also very mobile, which is problematic, because before you can threaten them, you must first find them. A ship sailing 20 knots can travel more than 800 kilometers a day, so geolocating a naval air group in the middle of the ocean is a difficult game of hide and seek. Jianbing 8 can only detect ships if they emit electromagnetic energy (radar, communication). Jianbing 8 is also likely able to detect early warning aircraft launched from an aircraft carrier, giving a general idea of the aircraft carrier’s location.

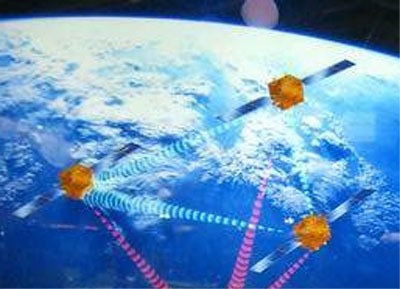

The Jianbing 8 constellation is formed by three satellites in three orbital planes, at 63 degrees. The satellites, possibly consisting of a primary satellite and two sub-satellites, are launched in a triplet similar to that of the US satellite constellation NOSS/Whitecloud, which is used to detect, identify, and locate radar and telecommunication emissions, particularly those from warships. This Jianbing constellation likely performs this function by locating them using a technique in which the time difference of arrival of emitted signals is measured and used to triangulate. Since 2010, nine of such triplets have been launched.

On November 6, 2021, China successfully launched a triplet of satellites, Yaogan 35 01-A, -B and -C. The satellites were placed in a circular orbit of almost 500 kilometers at 35 degrees inclination. Before the launch, China reported that the satellites would be used for "scientific experiments, land and resource logging, and other areas", but that’s probably a generic explanation to hide the satellites’ true purpose. It is believed that they may in fact be a continuation of the Jianbing 8 triplets and have a role in intelligence gathering. After the first successful launch, three more were executed in 2022.

Jianbing 8 satellite constellation. (credit: CAST) |

Yaogan 35 triplet of satellites. (credit: CCTV) |

Chuangxin 5 | Yaogan 30 – Ocean Surveillance

Yaogan 30 triplets are a relatively recent addition to China’s satellite detection system. The first triplet of this type was launched on September 29, 2017, under the designation Yaogan 30 01-A, -B and -C. Officially, the purpose of these satellites is to "conduct technical experiments on the electromagnetic environment," which is a euphemism for ELINT. This is consistent with the fact that ELINT satellites are often launched in triplets, such as the Jianbing 8 triplets. The advantage of a triplet is that satellites flying in tight formation, a few tens of kilometers away from each other, can triangulate and accurately locate the source of an electromagnetic signal. This is more difficult to achieve with a single satellite.

But, Yaogan 30 satellites do not fly in formation. The Yaogan 30-01 trio separated after launch and were placed 120 degrees apart. They are therefore too far apart to be able to triangulate signals, because there is not even an unobstructed line of sight between them. On the other hand, this type of layout corresponds to what is expected if three satellites are positioned in such a way that their visit frequency is maximized. Moreover, the satellites have good coverage of the Pacific Ocean, India, China, North Korea, and even Japan thanks to their low orbital inclination, the latitude that is important for China’s defense. In addition, the height of the track is remarkably low for ELINT satellites: usually these are placed relatively high, about 1,000 kilometers altitude, to increase their field of view. Imaging satellites, on the other hand, are placed low to increase their resolution while maintaining an acceptable field of view. Therefore, it is questionable whether the Yaogan 30 constellation is dedicated to ELINT: the only clues in this direction are images and official statements, which may be disinformation. The satellites could very well be small optical satellites that offer a high frequency of repetition. Up till July 2021, ten triplets of Yaogan 30 satellites have been put in space.

Yaogan 30 triplet of satellites. (credit: CCTV) |

The Yaogan 32-01-01 and 32-01-02 are a duo of military satellites with an unknown purpose. The visualization during the launch broadcast at CCTV hints at SIGINT satellites. They were launched on October 9, 2018; a second launch took place on November 3, 2021.

Yaogan 32 military duo satellites (2018). (credit: CCTV) |

The Yaogan 34 satellite is possibly the first of a new series of government optical remote sensing satellites, likely also used as military reconnaissance satellites. The satellite was described as an optical remote sensing satellite, mainly used in territorial research, urban planning, confirmation of land rights, road network design, crop yield estimation, disaster prevention and mitigation, and other areas. Yaogan 34, was launched in April 2021, Yaogan 34-02 followed in March 2022, in a 1100km/63.4° orbit.

The Gaofen 11 series was billed as a civilian Earth observation system but was militarily codenamed Jianbing 16.

Jianbing satellites [SCS, September 1, 2022]

| Jianbing # | Satellite Name | Year of Launch | Function/Sensors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jianbing 1 | Fanhui Shi Weixing 0-1 – 0-9 | 1975 – 1987 | Film/Photo reconnaissance |

| Jianbing 1A | Fanhui Shi Weixing 1-1 – 1-5 | 1987 – 1993 | Film/Photo reconnaissance |

| Jianbing 1B | Fanhui Shi Weixing 2-1 – 2-3 | 1992 – 1996 | Film/Photo reconnaissance |

| Jianbing 2 | Fanhui Shi Weixing 3-1 – 3-3 | 2003 – 2005 | Film/Photo reconnaissance |

| Jianbing 3 | Ziyuan 2-1 – 2-3 | 2000 – 2004 | Electro-Optical |

| Jianbing 4 | Fanhui Shi Weixing 3-1 – 3-3 | 2004 – 2005 | Film/Photo reconnaissance |

| Jianbing 5 | Yaogan 1, 3, 10 | 2006 – 2010 | SAR |

| Jianbing 6 | Yaogan 2, 4, 7, 11, 24, 30 | 2007 – 2016 | Electro-Optical |

| Jianbing 7 | Yaogan 6, 13, 18, 23 | 2009 – 2014 | SAR |

| Jianbing 8 | Yaogan 9, 16, 17, 20, 25, 31 | 2010 – 2021 | Elint (Ocean Surveillance) |

| Jianbing 9 | Yaogan 8, 15, 19, 22, 27 | 2009 – 2015 | Electro-Optical |

| Jianbing 10 | Yaogan 5, 12, 21 | 2008 – 2014 | Electro-Optical |

| Jianbing 11 | Yaogan 14, 28 | 2012, 2015 | Electro-Optical |

| Jianbing 12 | Yaogan 26 | 2014 | Electro-Optical |

| Jianbing 16 | Gaofen 11-01, 02, 03 | 2018, 2020, 2021 | Electro-Optical |

| Jianbing X | Yaogan 29, 33, 33R | 2015, 2019, 2020 | Probably SAR |

| Jianbing ? | Yaogan 35 | 2021, 2022 (3) | Probably Elint (Ocean Surveillance) |

| Jianbing ? | Yaogan 30 (Chuangxin 5) | 2017 – 2021 | Possibly Elint (Ocean Surveillance) |

| Jianbing ? | Yaogan 32 | 2018, 2021 | Unknown |

| Jianbing ? | Yaogan 34 | 2021, 2022 | Possibly Electro-Optical |

Conclusion

Reportedly, boosted by policy support, China’s aerospace market has grown rapidly in the past seven years, with an annual growth rate of more than 20% and China is now the world’s second largest commercial satellite owner after the US. According to the UCS Satellite Database, from 2015 to 2018, China launched fewer than ten commercial remote sensing satellites annually, but the introduction of support policies helped commercial players. In 2019–2021, the annual commercial remote sensing satellites that were launched were 21, 13, and 36 respectively while the amount for 2022 is expected to be more than 50.

Henk Smid is retired chief officer of the Royal Netherlands Air Force, space analyst and publicist of numerous space related articles. He has been an advisor to several national and international working groups on space-related topics for which he has prepared/written a series of analyses and projections [Defence, NATO, European Commission].

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

A Review Of The Book First Dawn

|

Review: First Dawn

by Jeff Foust

Monday, September 26, 2022

First Dawn: From the Big Bang to Our Future in Space

by Roberto Battiston, translated by Bonnie McClellan-Broussard

MIT Press, 2022

hardcover, 216 pp.

ISBN 978-0-262-04721-0

US$29.99

In contrast to astronauts, many of whom have written memoirs, few space agency leaders write books about their time in office or other topics, like former NASA deputy administrator Lori Garver in Escaping Gravity. An exception to this is Roberto Battiston, a physicist who spent four years as the president of the Italian space agency ASI and has written numerous essays and books on space and science topics. The latest, First Dawn, is now available in English.

The book is not a memoir, although he discusses some experiences he had during his time leading ASI in later chapters of the book. Instead, in nearly three dozen relatively short chapters, he takes the reader on a meandering path from cosmology to astrobiology to spaceflight and space policy.

| “The questions we ask ourselves are very similar to those asked by the philosophers of ancient Greece,” he writes, such as the nature of matter. “However, the context has changed, thanks to the development of experimental science.” |

Much of the book is fairly straightforward, as Battiston discusses the Big Bang and the evolution of the early universe, then moves to the formation of the Sun, our solar system, and the development of life on Earth and prospects of it elsewhere. Halfway into the book, he suddenly shifts back out to cosmology, discussing dark matter and dark energy, black holes, and related topics. That allows him to go into his participation on the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer project, a particle physics experiment on the International Space Station for more than a decade.

Battiston treads familiar ground for most of those chapters, with few new revelations about the cosmos, although an occasional insight. “The questions we ask ourselves are very similar to those asked by the philosophers of ancient Greece,” he writes, such as the nature of matter. “However, the context has changed, thanks to the development of experimental science. Four centuries after Galileo, today we know how to question nature and how to read the mathematical characters with which its book is written.”

What may be most interesting to readers are some of his views on space exploration and commercialization in the book’s final chapters, leveraging his time leading ASI. He recalls visiting SpaceX’s headquarters for meetings with Elon Musk and other executives, coming away highly impressed with the company and the facility (even if he says that plant is located “in the southern part of San Francisco”; Hawthorne, California, is in the Los Angeles area.) He notes he attended closed-door meetings there along with NASA and other space agencies and various companies—including Caterpillar, the construction machinery company—to discuss exploring and settling Mars. “In Europe,” he laments, “I have found myself participating in this type of discussion only in the context of universities and the research world.”

Europe, he writes, missed the boat on reusability: there was little discussion of it, he recalls, at an ESA ministerial meeting in 2014 that led to development of the Ariane 6 as Europe’s response to the Falcon 9; a year after that meeting, SpaceX landed its first booster. There was also a missed opportunity with smallsats, he argues, comparing the rise of Earth imaging company Planet, born from projects at NASA Ames, with the struggle to secure Italian government support for a smallsat project at the Terni location of the University of Perugia. “By mentioning this I certainly don’t mean to imply that an impressive and ambitious project like Planet Labs could have started in Terni, but in all honesty, I cannot rule it out,” he writes.

Those insights near the end of First Dawn help keep it from being just a run-of-the-mill space science book. One wonders what other glimpses behind the scenes of spaceflight we might get if more former space agency leaders started writing books.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Space FOr All-The European Space Conference

Leaders of five space agencies—NASA, ESA, CSA, JAXA and ISRO—participate in a panel at the International Astronautical Congress in Paris September 18. Officials from China and Russia, previously announced to also be on the panel, were absent. (credit: IAF) |

Space for (mostly) all

by Jeff Foust

Monday, September 26, 2022

The theme of last week’s International Astronautical Congress (IAC) was “Space for All”, or, as written, “Space for @ll”, the at-sign an apparent nod to a digital component that was largely absent at a conference that required one to be there in person to see all of the major sessions. But plenty of people did show up in person: when the IAC closed on Thursday, the International Astronautical Federation said more than 9,300 people registered—a record—from 110 countries.

As is often the case, though, what gets noticed is not who shows up but who does not. In the case of this year’s IAC in Paris, it was two major spacefaring nations that had little or no official presence at the largest conference of its kind: China and Russia.

| “Despite the political troubles on terra firma,” Nelson said, “you still see that professional relationship working in the civilian space arena.” |

Russia’s absence is understandable given its invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions by the West. Dmitry Rogozin, the former head of Roscosmos, had already been sanctioned for his role as deputy prime minister in the 2014 annexation of Crimea, and did not attend either the 2018 IAC in Germany or the 2019 IAC in the United States. He did, though, attend last year’s IAC in Dubai, and Roscosmos had a major presence in the exhibit hall, something that was lacking in Paris last week.

Civil space, particularly the ISS, is one of the few places where Russia still cooperates with the West, even if that cooperation is difficult at times. “This didn’t start just yesterday,” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said of cooperation with Russia in space during a heads-of-agencies panel at IAC September 18 that included him and the heads of other Western ISS partners—the Canadian Space Agency, European Space Agency, and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency—but neither Russia nor China. (India’s space agency ISRO was the only other agency on the panel.)

Nelson repeated comments he’s delivered many times over the last seven months about how ties between the US and Russia in space date back to the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project nearly 50 years ago. “Despite the political troubles on terra firma,” Nelson said, “you still see that professional relationship working in the civilian space arena.”

At a press conference immediately after the panel, Nelson revealed that he has talked with Yuri Borisov, who replaced Rogozin as head of Roscosmos in mid-July. “I told him that I look forward to seeing him at the first opportunity,” he said. It’s unclear when that opportunity might arise.

Nonetheless, that cooperation on the ISS continues. Last Wednesday, a Soyuz rocket launched the Soyuz MS-22 spacecraft to the station with NASA astronaut Frank Rubio and two Russian cosmonauts on board. Rubio was the first to fly under a seat exchange agreement completed last July between NASA and Roscosmos. In early October, Roscosmos cosmonaut Anna Kikina will fly to the ISS on the Crew-5 Crew Dragon mission with NASA and JAXA astronauts.

“This crew swap represents the ongoing effort of tremendous teams on both sides,” Rubio said in a call with reporters last month. “I think it’s important, when we’re at moments of tension elsewhere, that human spaceflight and exploration, something that both agencies are incredibly passionate about, remains a form of diplomacy and partnership where we can find common ground.”

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has affected not just civil space cooperation but commercial endeavors as well. International Launch Services (ILS) started more than 25 years ago as a joint venture of Lockheed Martin, Energia, and Khrunichev to jointly market the Atlas and Proton rockets commercially. The company is now owned by Khrunichev but has its headquarters in Northern Virginia, offering the Proton and Angara to commercial customers.

| “Truth be told, both the US government and the Russian government could choose to end ILS if they wanted to,” said Louradour. |

That was difficult even before the invasion: the Proton, once a major player in the commercial launch market alongside the Ariane 5 and Sea Launch’s Zenit-3SL in an era where geostationary communications satellites provided most of the demand, has faded both because of problems with the rocket and a market that had shifted. The Angara, set to replace it, has been slow to enter service.

Now, sanctions and export control restrictions make if effectively impossible for any Western customer to launch their satellites on Russian vehicles, even if they wanted to. OneWeb lost access to Soyuz rockets, arranged through a contract with Arianespace, in early March, and had to scramble to find new rides with ISRO and SpaceX.

ILS, though, remains in operation. “Truth be told, both the US government and the Russian government could choose to end ILS if they wanted to,” said Tiphaine Louradour, president of ILS, during a panel at World Satellite Business Week in Paris September 13. “We believe that they recognize the venture still has value in the ties and the relationships between the countries, and that it has merit and purpose to continue.”

She acknowledged, though, that there was little ILS could do now but to wait until relations improve with Russia. “I certainly do hope that, for much broader reasons than ILS, that this current situation will resolve,” she said. “Our job is remain ready and to engage with the community and our customers.”

Asked if ILS could broker launches for non-Western countries that are willing to continue working with Russia, Louradour suggested that would still be difficult. “Being a US company, we have to, and we do, remain fully compliant with all US laws and regulations regarding import and export. We are also compliant with the State Department licensing requirements,” she said. “Opportunities may be there, but we have to evaluate that through that filter.”

She said after the panel that the company was not just sitting around and waiting for a changed geopolitical climate, but instead making sure it was internally prepared to resume sales should that climate change for the better. “We’ll be ready to hit the ground running.”

While Russia’s absence at IAC was not unexpected—reportedly, Russian officials could not get visas to participate—China’s low profile was a different story. The country was not completely absent at the IAC: some officials attended to accept an award from the International Astronautical Federation for the Tianwen-1 Mars mission and give a talk about it. But China, after originally being slated to participate in the heads-of-agencies panel, bowed out at the last minute and did not otherwise have a high profile at the conference.

“Cooperation with China, that’s up to China,” Nelson said at the press conference. “There has to be an openness there, and that has not been forthcoming.” He did not mention the Wolf Amendment, the provision in appropriations bills dating back more than a decade that sharply restricts NASA’s ability to cooperate bilaterally with China in space without Congressional approval.

Nelson said there have been “little glimpses” of such cooperation, such as deconfliction of the countries’ Mars orbiter missions. “I would hope that, on occasions like that, we would continue to have this,” he said. “But, as most of the people observing, I think, would see, there’s not a lot of transparency with regard to the Chinese space program vis-à-vis the US.”

| “Cooperation with China, that’s up to China,” Nelson said. |

Some at the IAC wondered if the global space community might splitting into two or more blocs. One would led by Western countries and allies, such as signatories of the Artemis Accords. During the conference representatives of the 21 countries that have signed the Accords met in person for the first time, primarily to identify topics of discussion and future work to build upon the principles outlined in the Accords. Another would be led by China and perhaps Russia, who previously committed to work together on an International Lunar Research Station.

A few are trying to straddle that divide. Shortly before the IAC, the United Arab Emirates, which signed the Artemis Accords, announced an agreement to fly a small rover on a future Chinese lunar lander mission. That would be the second such rover built by the UAE; the first, Rashid, is slated to fly late this year on a commercial lunar lander built by Japanese company ispace that will launch on a Falcon 9.

ESA also has some ties with China, said Josef Aschbacher, ESA director general, at the press conference. That included work on climate research. “No one can afford to be not participating,” he said of working on climate change. “At the end of the day, there’s one planet, and you cannot divide it.”

However, the lack of Chinese and Russian participation at this year’s IAC appeared to be a sensitive point for the conference organizers. The heads-of-agencies plenary, like others at the conference, used an online service called Slido to solicit questions from the audience and allow them to vote for questions submitted by others. The question getting the most votes asked why, given the “Space for All” conference theme, neither China nor Russia was on the panel, particularly since both countries were slated to participate according to earlier versions of the program. Despite the audience interest, the panel moderators never brought up the question.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Saturday, September 24, 2022

A Great Visionary Leaves Us

Frank D. Drake 1930 – 2022

Frank Donald Drake, an astronomer who pioneered the field of SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) died on September 2 at the age of 92.

Born in Chicago, Drake showed an early interest in chemistry and electronics. He entered Cornell University as an undergraduate and a participant in the Navy’s Reserve Office Training Corps. Upon graduation, he was assigned to the U.S.S. Albany and put in charge of the ship’s electronics. He followed this interest upon entering Harvard University as a graduate student in radio astronomy.

After earning his PhD, Drake took a position with the newly constituted National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in Green Bank, West Virginia. In 1958, the fledgling Observatory purchased a radio telescope “kit” from the Blaw-Knox Corporation in order to quickly have a research-grade instrument until a planned, larger antenna could be built. A year later, the assembled telescope, with its 85 foot reflector, was outfitted for observations and dedicated to Howard Tatel, an engineer who designed its novel mount. This prompted the NRAO director, to suggest to Drake that he come up with a research program to use the telescope.

Drake decided to follow another of his long-standing interests, and do a search, at microwave frequencies, for extraterrestrial transmissions. The idea that intelligent beings elsewhere might be using radio as a communication mode was already old – both Guglielmo Marconi and Nikola Tesla had attempted to pick up signals from Mars that they could attribute to beings on the Red Planet. With the greater astronomical sophistication that had developed by the 1950s, Drake opted to point the Tatel telescope in the direction of two nearby stars, Tau Ceti and Epsilon Eridani, each at about a dozen light-years’ distance. For several weeks Drake alternately pointed the telescope at these stars. The receiver was a commercial receiver designed for shortwave listening, and he used a simple motor drive to sweep its tuning up and down the dial. He chose to look at frequencies adjacent to the radio emission line (1420 MHz) of neutral hydrogen, on the grounds that this naturally produced line would be known to any technically proficient civilization, and therefore would serve as a marker for the guidance of societies who might wish to make contact. Drake was unaware of a paper published in 1959 by two Cornell University physicists who were arguing for just such experiments, pointing out that anyone with technology that was at least as advanced as our own could send detectable radio signals.

Drake named this first, modern SETI experiment Project Ozma, a reference to the princess in Frank Baum’s books, as she was in a world “both wonderful and far away.”

Although Project Ozma didn’t detect any extraterrestrial transmissions, it nonetheless attracted world-wide attention. As a consequence, the National Academy of Sciences suggested that Drake organize a small conference to discuss the nature and potential of trying to find evidence of intelligence in the cosmos. In response, a group of about a dozen prominent scientists and engineers met during the summer of 1961 in Green Bank. As an agenda for this gathering, Drake wrote a simple equation, consisting of seven concatenated terms whose product would be the estimated number of galactic societies who were producing signals that we, at least in principle, could discover. This formulation has become known as the Drake Equation, and is cited as the second most-famous equation in science (after Einstein’s E=mc2).

Drake eventually worked at both Cornell, at the Arecibo radio telescope, and at the University of California, Santa Cruz. He became president of the SETI Institute after its founding in 1984. He continued to promote SETI even after his official retirement in 2010 at the age of eighty. As he said at the time, “I’m never going to retire from SETI.”

Frank Drake was a man of extensive influence, inspiring many of today’s SETI practitioners who, as students, were informed by his efforts. A book published in 1992 and co-authored with Dava Sobel, “Is Anyone Out There?”, describes his career in detail. He was a soft-spoken person of perpetual good humor and astounding patience. When asked whether his tranquil demeanor was due to dealing with his children, he smiled and responded “No. It was students.”

It is a rare scientific discipline for which the pioneer can live to see an idea and experiment become a continuing research endeavor, one that fascinates not just researchers, but the public at large. But that was the flowering of SETI, an effort that promises to someday deliver profoundly important news; namely, that Earth is not the only world to have spawned life able to seek out and find other worlds that have done the same.

Drake leaves behind his wife, Amahl, and two daughters, as well as three children from a previous marriage.