Since I was a young child Mars held a special fascination for me. It was so close and yet so faraway. I have never doubted that it once had advanced life and still has remnants of that life now. I am a dedicated member of the Mars Society,Norcal Mars Society National Space Society, Planetary Society, And the SETI Institute. I am a supporter of Explore Mars, Inc. I'm a great admirer of Elon Musk and SpaceX. I have a strong feeling that Space X will send a human to Mars first.

Friday, April 29, 2022

Thursday, April 28, 2022

Wednesday, April 27, 2022

Monday, April 25, 2022

A Review Of The Book The End Of Astronauts

|

Review: The End of Astronauts

by Jeff Foust

Monday, April 25, 2022

The End of Astronauts: Why Robots Are the Future of Exploration

by Donald Goldsmith and Martin Rees

Belknap Press, 2022

hardcover, 192 pp., illus.

ISBN 978-0-674-25772-6

US$25.95

Last week, a committee of the National Academies released the decadal survey for planetary science and astrobiology, the once-per-decade report outlining priorities for planetary science missions for NASA to pursue. The latest report recommended NASA continue its Mars Sample Return campaign and also two new flagship missions, one to the planet Uranus and another to orbit and land on Saturn’s moon Enceladus, which has a subsurface ocean that is potentially habitable.

| Goldsmith and Rees argue that AI can close the gap between robotic and human capabilities in space exploration. |

The report, while focused on robotic missions, also examined the potential for human exploration, particularly of the Moon through NASA’s Artemis program, to support planetary goals. It offered a cautionary note: “Currently, science requirements do not drive the Artemis capabilities. However, in the committee’s view it is imperative that Artemis support breakthrough, decadal-level science.” [emphasis in original] However, it endorsed one mission that combined robotic and human capabilities: a robotic rover called Endurance-A that would travel more than 1,000 kilometers across the South Pole-Aitken Basin, collecting 100 kilograms of samples that would be delivered to an Artemis lander for astronauts to return to Earth.

For the last couple of decades, there has been a truce between advocates of robotic and human space exploration, with an acknowledgement that the two can and should work together: robots serving as precursors and assistants for later human missions. But in The End of Astronauts, Donald Goldsmith and Martin Rees—a veteran science writer and the UK’s Astronomer Royal, respectively—argue that exploration beyond Earth orbit should be left to robots, a case that is certainly controversial but not necessarily compelling.

If that sounds like a familiar argument, it should be: Rees, for example, has been skeptical in the past about the benefits of human space exploration. The authors lay out the standard arguments against human missions, such as the cost and risk of sending humans to the Moon, Mars, or elsewhere. Robotic missions cost far less and their capabilities have been growing throughout the Space Age.

In particular, Goldsmith and Rees argue that artificial intelligence (AI) can close the gap between robotic and human capabilities. Future advances in AI, they claim, will enable robotic missions to effectively operate independently, collecting and returning data with little human interaction that today is required and thus slows the pace of missions like Mars rovers.

They overplay their hand with AI triumphalism, though. They cite a 2012 paper by one planetary scientist, Ian Crawford, who examined 18 different skills related to exploration and found human superior in 13 of them and tied with robots in another. No matter: “Current trends in artificial intelligence suggest that of the thirteen categories judged to favor humans in 2012, humans will remain on top in only a couple of them twenty to thirty years later: cognition and decision-making,” they argue, without offering any substantiation of that argument.

| The authors write, for example, that the Columbia disaster took place in 2013 (no, 2003) and that former astronaut Scott Kelly is now a US senator (no, it’s his twin brother, Mark.) |

That’s important because the progress of general-purpose AI has lagged predictions of its impending ascendence for decades, much like fusion power (the authors, for good measure, mention the moon as a source of helium-3 for fusion power without mentioning the lack of reactors that can use it.) Applications like self-driving cars—a sophisticated, but narrow, use of AI—have failed to keep pace with the statements of advocates, including Elon Musk, who acknowledged in a recent TED conference interview that Tesla’s work on self-driving cars fell short of goals he set for it. Given the limited applications of AI so far in missions, like the “AutoNav” feature to enable longer autonomous drives by the Perseverance rover, and the long development cycles for planetary missions, it’s hard to see AI advancing as quickly as the authors predict, undermining their case.

There is also a sloppiness with the overall book. There are many factual errors, mostly minor ones. The authors write, for example, that the Columbia disaster took place in 2013 (no, 2003) and that former astronaut Scott Kelly is now a US senator (no, it’s his twin brother, Mark.) In an early chapter they claim that SpaceX delivers cargo to the International Space Station for $1,250 per pound, but says in a later chapter the figure is $8,000 per pound. (Both are wrong: a NASA Office of Inspector General report in 2018 estimated the cost for both SpaceX and Northrop Grumman at $63,200 per kilogram, or $28,700 per pound, for the original series of cargo contracts; the authors, perhaps, included the mass of the spacecraft in their calculations, which NASA is not paying for.) Combined, the errors don’t give the reader much confidence in the arguments they make. Perhaps the authors were waiting for a fact-checking AI system.

Of course, governments don’t send astronauts into space exclusively or even primarily to do exploration: it’s one rationale of several, like geopolitics and national prestige. Goldsmith and Rees appear to acknowledge this, expecting the US and China to land humans on the Moon in the next decade or so, with Mars missions possibly by the 2040s but perhaps later.

The solar system is a pretty big place. Many of the destinations outlined in the planetary science decadal survey remain out of reach of human explorers for the indefinite future: it’s unlikely any contemporary reader will still be alive if humans do, one day, set foot on Enceladus or go into orbit around Uranus. If humans are already going to space, for prestige or profit, there’s room for them to do exploration as well, working with, and building upon, robotic counterparts.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

War At Sea Seen From Above

Photo of the guided missile cruiser Moskva burning, taken by a sailor on one of the vessels that went to its assistance. The cruiser was struck amidships by two Neptune missiles and was still burning the next day. A fire boat is behind the Moskva spraying water. The ship's life rafts are missing. |

War at sea, seen from above

by Dwayne Day

Monday, April 25, 2022

Less than two weeks ago, the world was stunned when a Russian warship, the guided missile cruiser Moskva, was struck by two Ukrainian missiles and sent to the bottom of the Black Sea—the largest warship sunk in combat since World War II. For some, it evoked memories of an event almost exactly 40 years earlier, when an Argentine cruiser was sunk by a British submarine. That conflict had a space component that is only slowly—very slowly—being revealed. It poses an interesting contrast to how much has changed when it comes to space assets and war at sea.

The Argentine cruiser ARA General Belgrano sinking on May 2, 1982, after being struck by a torpedo fired by a Royal Navy submarine. After the sinking, the Argentine government claimed that American “spy satellites” provided the British with the ship’’s position, which the United States denied. |

Tiny little islands

In early April of 1982, Argentine forces invaded the small, sleepy, sheep-filled archipelago known as the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic, which Argentina refers to as the Malvinas. Very quickly, British forces mobilized in response to retake the islands. Royal Navy warships sailed from ports in the United Kingdom only a few days after the invasion, but it took them several weeks to arrive at the cold, wind-swept islands. After that, the war became a bloody slugfest. The Argentines suffered 649 killed, including 323 men lost when the cruiser General Belgrano—a former US Navy warship—was sunk by a British submarine, and Great Britain suffered 258 of its soldiers, sailors, and marines killed. The Royal Navy lost two destroyers, two frigates, and three other vessels to Argentine Exocet missiles and bombs, including the converted container ship Atlantic Conveyor. As a Royal Navy auxiliary weighing 14,946 gross tons, she technically ranks as the largest naval vessel sunk since World War II, although not a surface combatant like the Belgrano… or the Moskva.

| After the Belgrano sinking, the Argentinians claimed that an American “spy satellite” provided the ship’s location to the British. |

The Reagan Administration initially sought a diplomatic solution to maintain favor with Latin American countries that it was enlisting in opposition to communist influence in Cuba, Nicaragua, and El Salvador. The public American position created the impression, even among some within the British government, that the United States was not helping out its longstanding ally. The reality was that there was extensive cooperation between the US Navy and the Royal Navy. The Americans made available any weapons that the Royal Navy required, essentially opening up the armories and allowing the British to take whatever they needed with the proviso that they would eventually reimburse the United States. That included one hundred of the most advanced version of the American Sidewinder air-to-air missile, to be mounted on Harrier jump jets.

A recent book on the Falklands naval war revealed that an Argentine aircraft carrier and a Royal Navy submarine stalked each other during late April 1982. The carrier eluded attack and spent the rest of the war in port, where it was observed in May by a US reconnaissance satellite. |

Targeting Argentine ships

There were some interesting and unusual revelations about intelligence operations and other covert actions that followed the 30th anniversary of the war. On the British side, one revelation was that the submarine HMS Conqueror, which sank the Argentine navy’s cruiser General Belgrano, later engaged in a highly secret operation to use a form of underwater scissors to cut and grasp a towed sonar array from a Warsaw Pact naval vessel.

The sinking of the Belgrano on May 2, 1982, was one of the most high profile events of the war. But it was not the only time a Royal Navy submarine stalked an Argentine ship. In recent years, more has become known about the cat-and-mouse chase between the Argentine navy’s aircraft carrier ARA Veinticinco de Mayo and another Royal Navy submarine, HMS Splendid. Previously it was thought that the carrier had simply headed to port to sit out the war. But due to the efforts of a diligent Argentine researcher Mariano Sciaroni and his book A Carrier at Risk, we now know that the two vessels came close to detecting and attacking each other on several occasions. Veinticinco had headed toward the Argentine coast after the Belgrano sinking, and Splendid never attained a firing position.

After the Belgrano sinking, the Argentinians claimed that an American “spy satellite” provided the ship’s location to HMS Splendid. A declassified telegram from the US ambassador to Argentina notes that he had been trying to stomp out the claims, which he believed (rightly or wrongly) to be untrue.

In recent years, it has become apparent that throughout the 1970s the United States Navy increasingly used signals intelligence satellites in low Earth orbit for tracking ships at sea. That capability has been known for decades, although the National Reconnaissance Office still has not declassified anything other than the early testing of this capability in the early 1970s (see “Spybirds: POPPY 8 and the dawn of satellite ocean surveillance,” The Space Review, May 10, 2021.) By the early 1980s, the US Navy was seeking to feed satellite ocean surveillance data directly into the missiles of its ships at sea. Details remain classified and it is unknown to what extent this capability was developed by the time of the Falklands War. The Royal Navy may have been able to obtain some data from the American system even if they were not able to fully exploit it (see “Shipkillers: from satellite to shooter at sea,” The Space Review, June 28, 2021.)

| So what was the VORTEX doing for the British? The most likely mission would have been intercepting communications between Argentina’s leadership and military forces within Argentina. |

In 2002, some information was released from Russia indicating that the former Soviet Union had sought to make its own ocean surveillance data available to the Argentinians. The Soviet Union operated a series of signals intelligence satellites as part of a larger program named Legenda, and one of these satellites was launched during the conflict. The Russians claim that information from the satellites allowed them to accurately determine that the British landing force would land on May 21. However, it is unclear from available sources whether the Soviets provided information to the Argentinians, and at least one source indicates that they did, but the Argentinian navy did not make use of the data.

There are other aspects of space and the Falklands conflict that have come to light in more recent years. One that has received increasing attention is the fact that the Argentinian Air Force sought to track the Royal Navy’s fleet as it traveled south by detecting the Doppler shift in satellite signals being sent to the fleet—which itself was practicing strict radio silence.

Secretary of State Alexander Haig with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. In early April 1982, Haig assured the Argentinian president that the United States was not providing the United Kingdom with satellite intelligence. Decades later it was revealed that the United States did provide the United Kingdom with satellite intelligence, although this may have occurred after Haig’s meeting. (credit: US DOD) |

The lion and the VORTEX

The United States did make some of its space intelligence assets available to the United Kingdom. National Reconnaissance Office Director Donald Kerr gave a speech at an NRO town hall meeting in December 2006, and the transcript was later released to GovernmentAttic.org. In a partially censored section of the transcript Kerr referred to the “25th birthday” of a satellite system. The NRO had celebrated this event both at its headquarters near Dulles International Airport in Virginia and at another location, probably an overseas ground site. “It’s extraordinary that this machine born in the analog age is still serving the country in the digital age,” Kerr said. The mission of the satellite is deleted, but Kerr said, “It had to go to war with one of our allies shortly after launch and supported the United Kingdom in the Falklands War. It then came back, in fact to the central Asian theater, and provided notable service there. Now it’s covering the sub-continent India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, still doing significant work. It had a mean mission life of three or four years. Here we are 25 years later and it’s a tribute to the designers and more importantly those that have nursed it along as it displayed all of the symptoms of old age many times over.”

Kerr was undoubtedly referring to a satellite that originally had the code-name VORTEX and was launched atop a Titan IIIC from Cape Canaveral in October 1981. The satellite was controlled from a ground station in England and was placed in a near-geosynchronous orbit, meaning that it could have been shifted from an initial position over the Atlantic Ocean to later cover Asia and eventually India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan (although independent satellite watchers dispute this.) The target for the VORTEX signals intelligence satellites, according to Jeffrey Richelson writing in The U.S. Intelligence Community, was originally Soviet “strategic communications,” meaning communications between missile, bomber, and submarine bases. But several American signals intelligence satellites reportedly entered service focused on one kind of target only to have their operators discover that they could be turned on other kinds of targets as well. The VORTEX satellites were a follow-on to an earlier series of communications intelligence satellites known as CANYON.

Kerr’s comments confirm a story that appeared in a 1997 book written by Mark Urban, UK Eyes Alpha: Inside Story of British Intelligence. Urban wrote:

The Falklands war of 1982 was regarded by most people in the defence and intelligence establishments as a textbook example of Britain’s “special relationship” with the USA in action. The Americans had made certain advanced weapons available to the British and had shared vital intelligence about the location of Argentine ground and naval forces. In Cheltenham, though, there were people who knew that this assistance had sometimes required special pleading. The National Security Agency, GCHQ’s U.S. counterpart, had not achieved global coverage with its sigint satellites by 1982. The craft which was in a position to help Britain monitor Argentine communications was being used by the Reagan administration to eavesdrop on central America, principally El Salvador. One of the GCHQ officers who liaised with NSA recalls, “We had to negotiate very hard to get it moved, and then only for limited periods.” During these spells of a few hours each, the satellite’s listening dish was reorientated towards the south Atlantic in order to help Cheltenham. The NSA did not monitor the downlinked take during these periods, asking GCHQ to alert them if there was anything of U.S. interest in the transmissions.

El Salvador would be an unlikely target for such a satellite considering that the United States already had ground forces in that nation and it seems improbable that a strategic intelligence asset would be focused on rebels operating in the jungle whose communications could be readily intercepted with aircraft and ground-based receivers. If the satellite was indeed focused on the western hemisphere, Cuba and/or Nicaragua were the more likely targets.

In 2015, the State Department produced another in its highly valuable Foreign Relations of the United States series of books. This one focused on the Falkland Islands war and included mention of a discussion that the US Secretary of State Alexander Haig had with Argentine officials in early April. According to a declassified summary: “The Secretary told President Galtieri that the reports that the U.S. has furnished intelligence and satellite information to the UK are untrue. We denied the British request. As a matter of principle we feel that allies should not spy on each other. Our satellite, moreover, was not in a position to collect data from this area. Had it been, we would not have furnished it to the British. He gave President Galtieri his personal guarantee.” The summary is in contrast both to Urban’s 1997 book and Donald Kerr’s 2006 speech, although perhaps the satellite was loaned to the British after Haig had met with the Argentine president. Despite Haig’s assurances to the Argentine dictator, President Ronald Reagan had decided that the United States would fully, if clandestinely, support the United Kingdom in its effort to regain the Falklands.

So what was the VORTEX doing for the British? The most likely mission would have been intercepting communications between Argentina’s leadership and military forces within Argentina, and the most immediate requirement would have been intercepting any communications indicating the launch of aircraft headed toward the Falklands. The Argentines would have had to assume that the British were listening and it would have made sense for them to launch their aircraft while maintaining radio silence. However, in his book, Urban noted that a British source indicated to him that there were limits to just how quiet the Argentines could be; they still had to communicate, after all. The more interesting aspect of Urban’s story is that this event was apparently what prompted the British to develop a signals intelligence satellite of their own, code-named ZIRCON, a plan they later abandoned in favor of paying the United States for access to its satellites.

| It is highly likely that US imagery satellites provided images of Argentine forces and defenses on the islands, as well as targets in Argentina such as airfields and the location of their remaining stockpile of Exocet anti-ship missiles, which were the target of a failed SAS commando raid. |

Whether or not the United States was eager to cooperate, American leaders may have felt required to cooperate at least as far as sharing signals intelligence data was concerned. In 1954, the United States and the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia signed the UKUSA Agreement, also known as the UK-USA Security Agreement, or occasionally the “Secret Treaty.” This agreement obligated the countries to share signals intelligence data, and delineated geographic responsibilities. The United States was responsible for Latin America, most of Asia, Russia, and northern China. Britain is responsible for Africa and the former Soviet Union west of the Urals. Assuming that the VORTEX satellite had initially set up shop over the Atlantic Ocean, it could have been officially used to collect signals intelligence data on Latin America—as required by the agreement—with that data automatically provided to the United Kingdom.

The VORTEX satellite was apparently still working as late as 2009. At the 2009 GEOINT Symposium, Director of the NRO Bruce Carlson mentioned an old spacecraft. “We have a satellite up there that is ten times older than we expected it to be. It has been up there this long [extends his arms out wide] and it has been up there this long [extends his arms out farther] and it’s still working. We expected it to do a mission that had to do with strategic, long-haul communications and today it’s helping us kill bad guys in the AOR [Afghanistan Area of Responsibility]. Now that’s as specific as I can get. But we do that because of the incredible contractor and NRO team that we have that nurses that satellite along and the young people that write software to change its functionality and keep it going.”

Other cooperation

This was probably not the only sharing of intelligence data between the United States and Great Britain during the war. It is highly likely that US imagery satellites provided images of Argentine forces and defenses on the islands, as well as targets in Argentina such as airfields and the location of their remaining stockpile of Exocet anti-ship missiles, which were the target of a failed SAS commando raid. A declassified imagery report from late May indicated that the carrier Veinticinco was in port, with no aircraft on deck. A deleted portion of a declassified documentary on the HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite implies that one of the satellites imaged the Falklands. The seventeenth HEXAGON mission was launched on May 11, 1982, and would have been able to photograph the islands from its polar orbit. However, its first reentry vehicle did not return until June 15, by which time the British had retaken the islands. If American satellite imagery played a role in the conflict, it came from the real-time imagery satellites and not the HEXAGON.

In 2020, John Ferris published Behind the Enigma: The Authorized History of GCHQ, Britain’s Secret Cyber-Intelligence Agency. Unfortunately, the book shed no new light on the intelligence sharing between the two countries. In fact, it omitted some information that had been released by the US government, such as Kerr’s 2006 speech. But in 2020, information was leaked that indicated just how much the United States’ National Security Agency was able to read encryption machines around the world, including those in Argentina. That may have provided significant military information to the NSA, which was then shared with the United Kingdom. It is unknown if American satellites provided the intercepts. Unfortunately, Ferris’ book did not shed much new light on the British ZIRCON signals intelligence satellite.

Other information about the space aspects of the conflict has come to light in more recent years, although not on the operational side but in the realm of US-British relations. In 2021, historian Dr. Aaron Bateman revealed that Britain’s experience during the war highlighted how much the country was dependent upon American intelligence, particularly space, assets (see “The secret history of Britain’s involvement in the Strategic Defense Initiative,” The Space Review, February 1, 2021.) That also may have made British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher more amenable to President Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative (commonly known as “Star Wars.”) Thatcher believed that to maintain access to American space intelligence collection systems, she needed to support Reagan’s project. She believed that doing so would have other values as well.

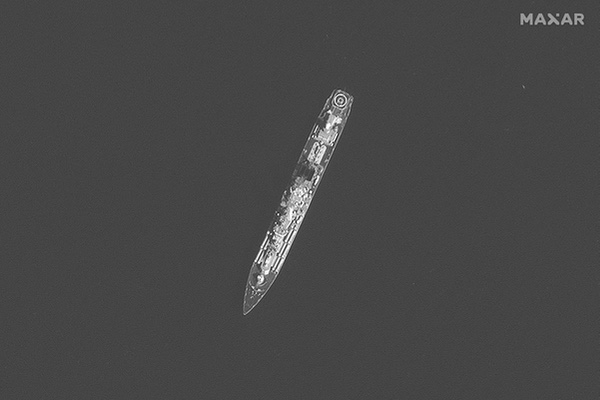

One of the last photos—possibly the last photo—taken of the Russian guided missile cruiser Moskva before the ship was hit by two Ukrainian Neptune missiles. Moskva sank a day after being struck. Commercial satellite imagery like this had been used by open source intelligence analysts to track Moskva’s movements in the weeks before the attack. (credit: Maxar) |

Battle in the Black Sea

The current war in Ukraine, and the saga of the Moskva, highlights just how much has changed in forty years. The United States—and Russia for that matter—has extensive intelligence assets in space. One of the stories of this war is just how much commercial remote sensing has grown, even in only the past few years, and how it has often allowed independent observers to confirm what has been happening on the battlefield, such as the Russian buildup prior to the invasion, and Russian activity and atrocities after the invasion. Open-source intelligence (OSINT) has played an important part in this war, including at sea. Independent naval analysts like H I Sutton have used satellite imagery, including commercial satellite-based synthetic aperture radar technology that was not even available to the military in 1982, to track Russian warships in the Black Sea, including the Moskva.

| Independent naval analysts like H I Sutton have used satellite imagery, including commercial satellite-based synthetic aperture radar technology that was not even available to the military in 1982, to track Russian warships in the Black Sea, including the Moskva. |

Moskva was laid down at the Nikolaev shipyard in Ukraine on the Black Sea in 1976, launched in 1979, and commissioned in 1982. The US intelligence community monitored the development of the ship and his successors (Russian warships are referred to as “he” in Russia.) As of December 1980, while still under construction, the ships had been designated “445-F” by US intelligence analysts, and the lead ship was then expected to enter sea trials by the end of 1981, as eventually happened. The ship was initially designated BLACKCOM 1 (for Black Sea Combatant), and then when observed at sea with the name Slava, NATO designated them the Slava-class.

The Slava-class cruisers were equipped with a formidable arsenal of anti-ship missiles intended to attack American aircraft carriers. But with the decline of the Russian Navy after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the three operational ships spent much time at port. They often served as flagships, with the Slava—renamed Moskva—serving as the Russian Navy’s Black Sea flagship.

A week before the Moskva sinking, in an April 7 article, H I Sutton, with the help of independent analyst Damien Symon and others, noted that Moskva was following a rather predictable pattern. If they noticed that based upon publicly available information, it’s not hard to believe that Ukrainian coastal defense forces did as well. On the evening of April 13, Moskva was struck by two Ukrainian Neptune missiles launched from a coastal battery. Based upon images taken by a sailor on one of the rescue vessels, the missiles struck the cruiser port amidships, causing extensive fires. The crew apparently abandoned ship, although it is unknown how much they fought to save the Moskva before taking to the life rafts. Russian statements on the war, and what happened to the ship, have zero credibility—for example, after the Russian government stated that the ship had been lost in a storm while being towed to port, photos of the burning ship being assisted by tugs showed calm seas.

As Sutton has noted, one of the last images taken of the Moskva was by a Maxar commercial satellite. After the cruiser was hit and rescue ships rushed to its aid, on April 13 a commercial synthetic aperture radar satellite imaged the cruiser and several smaller ships surrounding it. Sutton shared that image to Twitter and, days later, a merchant sailor’s cellphone images and video of the ship depicted the same scene, although this time from sea level. Since that time, Sutton has been using satellite imagery to detect any salvage operation, and new imagery may depict an oil slick at the site of the wreck.

European Sentinel satellite image from late March. A Russian Alligator-class ship is burning at dockside at upper right. Two Russian Ropucha-class landing ships fled after the initial explosions and had fires on their decks due to exploding debris. Somebody who downloaded the image off the Sentinel website noticed a ship at lower left doing many circles, as if it was suffering a mechanical malfunction. This may be one of the damaged Ropucha-class ships. |

The images of the Moskva are not the only examples of satellite imagery showing the naval aspects of the Ukraine war. After a Russian Alligator-class amphibious landing ship blew up at dockside in late March, satellite imagery showed the destroyed vessel sunk alongside its dock. Web camera footage had previously shown the ship on fire and two other Russian vessels rapidly moving away, both of them also on fire, apparently from debris that landed on their decks. Shortly thereafter, a European Sentinel satellite image of the area was downloaded from the Sentinel website and circulated on the Internet. It not only showed the ship burning at dockside, but also a very curious event taking place out in the Black Sea—a vessel circling repeatedly, as if it had suffered a mechanical failure. This was apparently one of the two damaged ships that had fled the port, obviously in some distress.

| Open-source analysts have insight and determination, as well as the Internet, which enables rapid sharing of information. Unlike 40 years ago, we can now watch the war as it unfolds. |

Open-source intelligence analysts like Sutton and others have some incredibly powerful tools available to them, often at no cost. Space-based synthetic aperture radar was not even available to the United States in the early 1980s, yet the data is publicly posted today not long after it is sent to a ground station. Today’s commercial imaging satellites are not as good as American military systems in the early 1980s in terms of resolution (a function of the camera system’s aperture), but they are plentiful, and a lot of their data is made freely available.

But open-source analysts can only use the data that is, by definition, public. Not only do they lack access to more powerful military satellites, they don’t have access to data produced by many of the same satellites that is not released. They also do not have access to signals intelligence data that can be used to track ships at sea by their radar and radio emissions (although in Ukraine’s ground war, the Russians have often used unencrypted communications that have been intercepted even by amateur radio operators). Open-source analysts also lack powerful processing tools that can merge data from multiple sources and geolocate targets. What they do have, however, is insight, and determination, as well as the Internet, which enables rapid sharing of information. Unlike 40 years ago, we can now watch the war as it unfolds. From the ground, the sea, and above.

Dwayne Day can be reached at zirconic1@cox.net.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Sunday, April 24, 2022

Saturday, April 23, 2022

Friday, April 22, 2022

Thursday, April 21, 2022

Wednesday, April 20, 2022

Tuesday, April 19, 2022

Red Silence

Red Silence

Future communication in the Martian atmosphere will not be the same as that on Earth, according to a new study.

Scientists discovered that the speed of sound travels more slowly on the red planet while “mostly, a deep silence prevails,” CNET reported.

Researchers used sound recordings from NASA’s Perseverance rover to calculate how sound travels on Mars and describe the planet’s soundscape.

The data from the rover’s SuperCam instrument showed that there are two sound speed limits on Mars: Low-pitched sounds travel at about 537 mph (240 meters per second) but higher-pitched sounds move at 559 mph (250 meters per second).

In comparison, the speed of sound on Earth is about 767 mph (343 meters per second).

The team explained that the slower speed is caused by the planet’s thin atmosphere, which is made up primarily of carbon dioxide. Mars’ atmosphere also muffles sound, which prevents high-pitched noise from traveling at all.

Still, the authors noted that the speed of sound could change depending on seasonal and temperature fluctuations on the planet.

They added that since the speed of sound is affected by temperature, they were able to measure large and rapid temperature changes on the Martian surface that other sensors had been unable to detect, according to Science Alert.

Click here to get a glimpse of how familiar Earth sounds change on the red planet.

Review Of The Book Never Panic Early

|

Review: Never Panic Early

by Jeff Foust

Monday, April 18, 2022

Never Panic Early: An Apollo 13 Astronaut’s Journey

by Fred Haise with Bill Moore

Smithsonian Books, 2022

hardcover, 216pp., illus.

ISBN 978-1-58834-713-8

US$29.95

Fifty-two years ago yesterday, Apollo 13 splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, safely returning three astronauts after an explosion on their way to the Moon crippled their spacecraft and put their lives in jeopardy. The story of the mission has been told many times, as well as the life of its commander, Jim Lovell. The mission’s command module pilot, Jack Swigert, died of cancer in 1982 before he could tell his life story. One would think surely that the mission’s lunar module pilot, Fred Haise, alive and well today at age 88, would have written about his life, like so many other astronauts.

| After his first flight in a training aircraft, “I walked away from that plane knowing that I was no longer going to be a journalist.” |

He hadn’t, until now. Never Panic Early is a straightforward autobiography about a man who will be forever linked with Apollo 13, but whose career in the military, at NASA, and in industry goes far beyond that single spaceflight.

Unlike many other early astronauts who had a passion for aviation from an early age, Haise’s interest in flying came much later. Through high school and junior college his interest was primarily in journalism, but when he failed to secure a scholarship to attend the University of Missouri to study journalism there, he decided to join the military, enlisting the Naval Aviation Cadet Program. After his first flight in a training aircraft, “I walked away from that plane knowing that I was no longer going to be a journalist.”

After a brief career in the Marines, he completed a college degree and became a pilot for NASA, first at Lewis Research Center in Cleveland and later at Edwards Air Force Base, the latter allowing him to go to test pilot school, run at the time by Chuck Yeager. In 1966, he became a NASA astronaut, initially supporting work on the Lunar Module at Grumman before being assigned to the backup crews for both Apollo 8 and Apollo 11.

His chapter on Apollo 13 is similar to previous accounts of the mission, with just a few additional details. He explained that the urinary tract infection he got came from a request from Mission Control not to vent urine overboard because it was affecting tracking of the spacecraft, which meant they stored urine in whatever containers were available, including backup bags from the Gemini program. “Lazy me made the choice to leave a Gemini bag attached to my body, for over a day, to make the urine-transfer process easier,” he writes, but that led bacteria to build up and cause the infection.

Haise returned to a backup role on Apollo 16, an assignment that originally put him on a path to command Apollo 19. That mission, though, was cancelled before Apollo 16’s launch 50 years ago this month. Instead, Haise got involved in the shuttle program, first as part of NASA teams evaluating contractor proposals and, eventually, flying the first orbiter, Enterprise, on a series of glide tests at Edwards. He was assigned to fly on the STS-3 shuttle mission, which originally was intended to go to the Skylab space station to attach a booster to raise its orbit. However, delays in the shuttle meant that Skylab reentered nearly two years before the first shuttle launch. Haise said at that point, rather than wait for another chance to go to space, “I set my sights to move into executive management,” leaving NASA in 1979 to work for Grumman until his retirement in the mid-1990s.

While the book is an autobiography, much of it focuses on his professional life rather than his personal one. The end of his first marriage—a casualty, like others from that era, from the race to the Moon—and the start of his second get only brief mentions in the book. By contrast, his corporate adventures later in his career at Grumman get much more attention.

The book’s title comes from a phrase that came up many times as a pilot and astronaut: when a problem appears, don’t panic but instead calmly work to solve it. Haise successfully did that through his career, be it overcoming a problem with an aircraft in flight or a spacecraft heading to the Moon.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Investing In These Innovations Will Get Us To Mars And Beyond

Investing in these innovations will get us to Mars and beyond

by Dylan Taylor

Monday, April 18, 2022

Last year was historic for Mars exploration. While humans have been exploring the planet in some capacity for 50 years, 2021 marked several firsts in space exploration, including the first time probes from three countries arrived at the Red Planet.

| Some of the most scalable technologies have proven their value in preliminary stages and hold long-term potential for deep space exploration. |

Progress is partially due to the convergence of many exciting trends that are helping to advance space innovations within the sector. Startups have flocked to the space industry to bring sophisticated technologies like quantum computing, phased array radar, artificial intelligence, cubesats, and other services. Along with NASA, the NewSpace sector is working to transform innovations that can help us reach and settle Mars.

While many unproven technologies have entered the market, investors will want to commit capital to disruptive and differentiated technologies. Some of the most scalable technologies have proven their value in preliminary stages and hold long-term potential for deep space exploration. These are the lucrative innovations redefining Mars exploration.

Inflatable heat shields

The largest vehicle that humans have landed on Mars is the Perseverance rover, roughly the size of a car. But for astronauts to arrive on Mars safely one day, we’ll need much larger spacecraft and thus protection for them as they enter the Martian atmosphere.

Heat shields can help support larger vehicles, but current versions are rigid and the size needed to transport large spacecraft that carry humans won’t fit properly into a rocket. However, NASA’s inflatable heat shields in development could allow heavier spacecraft to enter and land on the Martian surface thanks to its flexible design.

NASA and the United Launch Alliance’s current six-meter inflatable heat shield works by expanding and inflating before it enters the atmosphere, acting as a brake to slow the spacecraft and land cargo and astronauts safely on the surface and take up less space in a rocket. Ultimately, this cutting-edge prototype, expected to launch later this year, could land much larger spacecraft on any extraterrestrial surface with an atmosphere.

New models are still progressing but could help deliver large payloads of water and supplies to worlds with thick atmospheres. According to a new market report, the aerospace segment for the overall heat shield market can expect 3.5% annual growth by 2027. While NASA is the technology’s leading developer, the NewSpace sector has many opportunities to drive competition by either developing shields or manufacturing needed materials in a market ripe for disruption and competition.

Nuclear propulsion systems

Astronauts will have to travel hundreds of millions of kilometers in deep space to reach Mars. Therefore, updated propulsion systems will be critical to sending astronauts safely and quickly to the planet. Scientists have found that while it’s uncertain which propulsion system will take astronauts to Mars in the future, it will need to be nuclear-enabled to reduce long travel times. NASA is currently working on both nuclear electric and nuclear thermal propulsion research and testing projects that use nuclear fission. It anticipates sending astronauts to the Red Planet by the 2030s. However, while the nuclear electric rocket is more efficient, its thrust is weaker than nuclear thermal propulsion.

| As Elon Musk promises to get humans to Mars and NASA sends people to the Moon, these innovations may be the tip of the space investment iceberg. |

It’s not just NASA focusing on nuclear innovations. Space companies are eyeing innovations to propel the industry forward, too. Blue Origin, Lockheed Martin, and General Atomics were recently hired by the the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to test nuclear propulsion above low Earth orbit as part of a larger project by 2025. Adding more fuel to the flame, Elon Musk has admitted that nuclear power is critical to habitable bases on Mars.

Whichever system is superior, nuclear propulsion will greatly reduce a space crew’s time away from home. Along with other NewSpace players, NASA is continuing to develop, test, and mature these crucial parts and functions of different propulsion systems to reduce the risk and challenges of the first human crewed mission to Mars and back. It’s no surprise that the overall global space propulsion market will increase from $6.7 billion in 2020 to $14.2 billion by 2025.

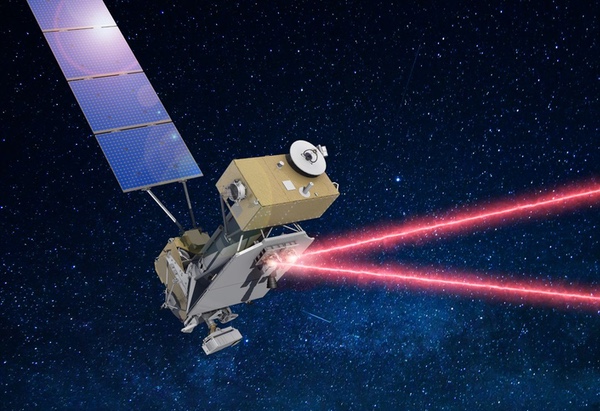

NASA is testing laser communications in Earth orbit now and plans a deep-space demonstration of the technology on the upcoming Psyche mission. (credit: NASA/GSFC) |

Laser communications

In the future, crewed missions to Mars may use lasers to share information with Earth. Laser communication systems used on the way to and on Mars could send vast amounts of real-time data, including high-definition images and video feeds, back home. The innovation could be a game-changer for efficient communications and according to a recent NSR report, the market for laser comm terminals holds a $3 billion opportunity over the next ten years. Not only will such innovation help us communicate with astronauts, but we can more directly view their adventures as they navigate life on the Red Planet.

NASA was one of the first industry disruptors, proving that laser communications were possible from the Moon in 2013. Future tests will navigate various operational scenarios to finesse pointing systems and challenges. NASA's Deep Space Optical Communications will be tested on the Psyche mission to the asteroid belt, scheduled to launch later this year. It’s expected to increase spacecraft communications performance and efficiency by 10 to 100 times compared to conventional operations.

Corporations at the intersection of communications, big tech, and NewSpace are also getting on board to influence the laser communications niche. Google X and Facebook Connectivity Lab’s collaboration with Mynaric resulted in stable air-to-ground communications.

SpaceX’s Starlink will also boast inter-satellite laser links (ISL), among the promising commercial ventures which harness interconnection of high-altitude platforms like satellites to use as a foundation for high-performance optical networks.

As Elon Musk promises to get humans to Mars and NASA sends people to the Moon, these innovations may be the tip of the space investment iceberg. Once humans reach Mars safely, these innovations may take on advanced capabilities, providing us with a wealth of information. When nations and companies collaborate to achieve the seemingly impossible, we create new opportunities that have both extraordinary and practical applications for life on Earth and beyond.

Dylan Taylor is chairman and CEO of Voyager Space. He is a global entrepreneur, investor, and philanthropist, and the founder of Space for Humanity, a nonprofit organization that seeks to democratize space exploration.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

A Second Chance At The Moon

A second chance at the Moon

by Jeff Foust

Monday, April 18, 2022

Companies rarely get second chances at competitions they lose. Unless a contract is overturned by a protest or other legal action, bidders who lose out on government contracts have to lick their wounds and try again on a future program.

| “Today’s announcement is what I said to Congress,” Nelson said. “I promised competition, so here it is.” |

But for the companies that lost out in the Human Landing System (HLS) competition to SpaceX last year, an effort that prompted both unsuccessful protests with the Government Accountability Office and a lawsuit rejected in federal court, there will be a second chance to offer landers capable of taking astronauts to and from the lunar surface. That second chance, though, doesn’t mean a repeat of the same teams offering the same landers.

On March 23, in an announcement made on short notice days before the release of the agency’s fiscal year 2023 budget proposal, NASA announced a new initiative, called Sustaining Lunar Development. The program will support creation of a second lander alongside SpaceX’s Starship selected for the HLS program’s single Option A award last year (see “All in on Starship”, The Space Review, April 19, 2021).

NASA officials said Sustaining Lunar Development was fulfilling a pledge to have competition in the overall HLS effort, something originally envisioned by selecting more than one company for an Option A award. Last April, NASA officials explained that they had the funding for only a single award, which went to SpaceX for $2.9 billion, an amount that was far less than competing bids from Blue Origin and Dynetics.

“Today’s announcement is what I said to Congress,” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said in a call with reporters about the announcement, referring to statements to members who pressed NASA last year to select a second lunar lander provider. “I promised competition, so here it is.”

It is, though, a different kind of competition than was originally envisioned under HLS. The winning company will move directly into work on a more advanced lunar lander designed to support NASA’s “sustainable” phase of lunar exploration later in the decade. That moves from initial “sortie” missions, carrying two people who spend a week on the surface, to “excursion” missions lasting up to a month with four people.

“Beyond Artemis 3 we want to increase the healthy competition and advance our lunar capabilities to support more science, more exploration, and an emerging lunar marketplace,” Jim Free, NASA associate administrator for exploration systems development, said at the briefing.

Agency leaders were quick to explain that the decision to proceed with Sustaining Lunar Development did not reflect any buyer’s remorse or other dissatisfaction with SpaceX. The GAO protest and lawsuit delayed the start of SpaceX’s HLS work by more than half a year, but NASA managers said they were pleased at SpaceX’s work since then.

“I’ve spoken recently with [SpaceX president] Gwynne Shotwell, and our teams are making good progress on the demonstration HLS award,” Nelson said, which includes the Artemis 3 landing.

| “Many folks have told us, ‘We’ve learned a lot and we think our bids can be better this time,’” Free said. |

SpaceX will not be eligible to compete for the Sustaining Lunar Development award in order to preserve competition (although, agency procurement officials later said, bidders could have SpaceX as a subcontractor if, for example, they wanted to launch their landers on SpaceX vehicles.) Instead, NASA will exercise an option in SpaceX’s HLS award, called Option B, to bring its Starship lander up to the specifications for those later sustainable missions.

The announcement left unanswered many details about the new program, not the least of which was its budget. Blue Origin’s and Dynetics’ bids for the original HLS competition were significantly higher than SpaceX’s winning bid, and that was for the original Option A capability and not the greater demands of the new competition.

Agency leaders declined at the time to discuss budget details, noting the fiscal year 2023 budget proposal would soon be released. “Many folks have told us, ‘We’ve learned a lot and we think our bids can be better this time,’” Free said.

That budget proposal, though, didn’t answer many questions about the budget for lunar lander development. After NASA got its full request of $1.195 billion for HLS in a fiscal year 2022 omnibus spending bill approved in mid-March, the 2023 proposal asked for $1.486 billion for HLS. It did not, though, spell out how much of that would go to Sustaining Lunar Development versus the existing Option A and planned Option B awards to SpaceX.

“I can’t break that out for you,” Free said when asked in a media teleconference about the budget proposal March 28 for how the HLS funding would be allocated. “We’re not going to break it out because then we give the number that is available for the procurement, and that changes how the procurement is run.”

However, more than two years ago, when NASA released its fiscal year 2021 budget proposal, it included estimates for funding of the HLS program for 2021 through 2025 while NASA was still considering proposals for initial “base period” contracts, and long before requesting Option A proposals.

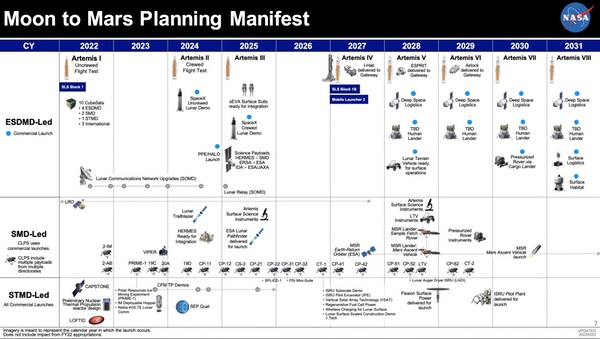

There will also not be a rush to develop that second lander. NASA used the budget rollout to release an updated timetable for the Artemis program, with the uncrewed Artemis 1 launch this year and Artemis 2 in 2024. The Artemis 3 mission, with the SpaceX landing on the Moon, was still set for 2025. However, Artemis 4 would not follow until 2027, and that would be a mission only to the lunar Gateway, delivering a habitation module to be built by Europe and Japan. The next landing mission, Artemis 5, would be in 2028, and be the first opportunity for that second lunar lander to fly.

A chart from a NASA budget presentation showing that, after Artemis 3 in 2025, the next Artemis crewed lunar landing would not be until Artemis 5 in 2028. (larger version) |

Despite uncertainties about cost and schedule, companies that bid on the original HLS competition are lining up to express their interest in Sustaining Lunar Development. That included Blue Origin, which protested the SpaceX HLS award to the GAO and later filed suit, unsuccessfully, in the Court of Federal Claims. “Blue Origin is thrilled that NASA is creating competition by procuring a second human lunar landing system,” the company said in a statement after NASA’s initial announcement about Sustaining Lunar Development. “Blue Origin is ready to compete and remains deeply committed to the success of Artemis.”

The same was true for Dynetics, which also filed a protest with the GAO but, unlike Blue Origin, didn’t go to court when the GAO rejected its protest. “As a current performer on NASA’s Appendix N contract, we have made great progress in our lander design and risk reduction,” a reference to risk reduction awards NASA made last September to several companies for future lunar landers that is part of its Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP) program.

However, those statements don’t mean that those companies will bid, or bid with the same teammates as the original HLS competition. Blue Origin’s bid was part of its “National Team” that included Draper, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman. Blue Origin, Lockheed, and Northrop all received NextSTEP Appendix N awards, but even then Lockheed and Northrop officials said they were leaving the door open to alternatives to the National Team.

At a March 30 webinar, Northrop officials said the company had yet to decide how they would participate in Sustaining Lunar Development. “We’ve done our own studies on the Human Landing System and we’ve worked with the National Team and Blue Origin,” said Rick Mastracchio, director of business development for human exploration and operations at Northrop Grumman. “Right now we’re in the decision-making process on that, and hopefully that will be a decision that comes out in the next few weeks.”

| “That changes the discussion of what capability you want to bring to the table,” Lightfoot said of the new competition. “For us, anything we do we want to be extensible to Mars. That’s important to us.” |

Lockheed Martin is also considering its options. The announcement of the program and the release, a week later, of the draft request for proposals, came just before the annual Space Symposium conference in Colorado Springs, Colorado, a major space industry meeting. Some companies, like Lockheed, used the event to set up meetings with prospective partners for the competition.

“Space Symposium was actually a perfect opportunity for us because anybody we want to talk to, we can get together like that,” said Robert Lightfoot, the executive vice president for Lockheed Martin Space, during an interview at the conference.

Lightfoot, a former NASA associate administrator and, for more than a year, acting administrator, said the company planned to participate in the Sustaining Lunar Development competition but hadn’t decided on a specific teaming strategy. “We’re going to be in the game somewhere.”

He emphasized that the company didn’t see the new competition as a repeat of the original HLS competition, which at the time was driven by a goal of returning humans to the surface of the Moon by 2024. “That changes the discussion of what capability you want to bring to the table,” he said. “For us, anything we do we want to be extensible to Mars. That’s important to us.”

While the National Team had four major companies, the Dynetics bid featured an even larger group of companies and organizations. One of the major ones was Sierra Nevada Corporation’s space unit, which has since been spun off in a separate company called Sierra Space.

In an interview, Tom Vice, CEO of Sierra Space, suggested that if the company participates in the Sustaining Lunar Development competition, it would be with Blue Origin. The two companies are currently working closely together on Orbital Reef, the commercial space station concept that was one of three that won NASA funding in December for initial studies.

“We have a very unique, strong relationship with Blue Origin,” he said. “We would probably think about how do we partner with them.” He added that he didn’t see the company leading its own team to bid on the lander, focusing its efforts instead on development of its Dream Chaser vehicle and its support for Orbital Reef.

Those decisions will need to come soon. NASA expects to release a final version of the lander RFP in the summer, with proposals due 60 days later. That would allow NASA to make a contract award by January 2023.

“This budget is a really good start to the competition,” Bob Cabana, NASA associate administrator, said in a call about the proposed 2023 budget. “This gets us on the right path.”

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Monday, April 18, 2022

Sunday, April 17, 2022

Thursday, April 14, 2022

Review NASA Missions To Mars

|

Review: NASA Missions to Mars

by Jeff Foust

Monday, April 11, 2022

NASA Missions to Mars: A Visual History of Our Quest to Explore the Red Planet

by Piers Bizony

Motorbooks, 2022

hardcover, 196 pp., illus.

ISBN 978-0-7603-7314-9

US$50

As NASA publicizes milestones in its Artemis program to return humans to the Moon—the rollout and testing of the Space Launch System rocket ahead of its first launch, an upcoming competition to select a second company to develop a crewed lunar lander—agency officials emphasize their long-term goal remains on Mars. “Our ultimate goal is putting people on Mars,” said Jim Free, NASA associate administrator for exploration systems development, at a House Science Committee hearing last month. “It’s getting two people to Mars, on the surface for 30 days, getting them there and back safely. Everything we do should be driven by that on the Moon.”

| Chaikin cites a comment Wernher von Braun made in 1954, when he predicted it might be a century or more before humans set foot on Mars. “I hope it turns out it he was just a bit too conservative, because I want to live to see it.” |

A new book illustrates that long-running interest in Mars exploration. NASA Missions to Mars is primarily a picture book about past, ongoing, and proposed missions to Mars. Prolific author Piers Bizony compiled dozens of images from Mars missions, along with illustrations of proposed missions and other concepts, to provide a high-level overview of the interest in exploring the Red Planet.

Bizony, in the book’s preface, calls NASA Missions to Mars “a family-friendly, nonacademic, almost purely visual celebration” of the past and future of Mars exploration. That is an accurate assessment. There’s only a few pages of text for each chapter, setting the stage for the images that follow. Most of that information, as well as the images, will be familiar to those with at least a passing knowledge of Mars exploration.

The book is, though, a good overview of Mars exploration for those unfamiliar with it, from Mars in early science-fiction works through the decades of robotic missions to proposals for sending humans to the planet. Most of those images, from Viking to Perseverance, are well known, but there are some hidden gems, like old illustrations from decades ago of concepts for humans missions to Mars.

Andrew Chaikin contributes an introductory essay in the book, talking about his childhood interest in Mars. He planned to pursue a career in planetary geology, seeing it as a steppingstone to becoming an astronaut, and was even an intern on the Viking science team while in college. His career took a different turn, but he crossed paths with Mars time and time again as a science writer. As for humans on Mars, “I have my doubts” about proposals for sending humans to Mars in the 2030s, a notional goal NASA leaders have offered. He cites a comment Wernher von Braun made in 1954, when he predicted it might be a century or more before humans set foot on Mars. “I hope it turns out it he was just a bit too conservative, because I want to live to see it.”

Bizony, in the preface, offers similar thoughts, lamenting the delays in sending humans to Mars throughout his adult life. But, he adds, “I am very much still alive and so is the dream of reaching Mars.” It’s just that some people are getting a bit impatient.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new accoun