Since I was a young child Mars held a special fascination for me. It was so close and yet so faraway. I have never doubted that it once had advanced life and still has remnants of that life now. I am a dedicated member of the Mars Society,Norcal Mars Society National Space Society, Planetary Society, And the SETI Institute. I am a supporter of Explore Mars, Inc. I'm a great admirer of Elon Musk and SpaceX. I have a strong feeling that Space X will send a human to Mars first.

Sunday, October 30, 2022

Saturday, October 29, 2022

Thursday, October 27, 2022

Tuesday, October 25, 2022

Tuesday, October 18, 2022

A Review Of Boldly Go by William Shatner

|

Review: Boldly Go

by Jeff Foust

Monday, October 17, 2022

Boldly Go: Reflections on a Life of Awe and Wonder

by William Shatner with Joshua Brandon

Atria Books, 2022

hardcover, 256 pp.

ISBN 978-1-6680-0732-7

US$28

One year ago, Blue Origin’s New Shepard performed its second crewed flight, taking four people just beyond the Kármán Line on a ten-minute suborbital flight. The most famous person on that flight was William Shatner, Captain Kirk from the Star Trek television series and subsequent movies. He had, as widely reported at the time, a very emotional reaction to the flight immediately after landing, comparing the Earth to life and the blackness of space to death (see “Black ugliness and the covering of blue: William Shatner’s suborbital flight to ‘death’”, The Space Review, October 18, 2021).

| “And so, I thought, I must go to space. Not because I was Captain Kirk, but because I’m alive.” |

That experience resurfaced with the publication this month of Shatner’s new book, Boldly Go, the latest in a series of memoirs he’s written over the years. An excerpt of the book, published by Variety earlier this month, recounted aspects of that flight, including his recollections of the “cold, dark, black emptiness” of space: “all I saw was death.” That generated another wave of publicity about the flight, casting it in a negative light. “Welp, now I definitely don’t want to go to space,” wrote Emma Roth of The Verge, linking to the Variety excerpt. “[I]t sounds kind of terrifying.”

There is more to the story of the flight, though, told in Boldly Go. Shatner devotes a chapter of the book to his flight, titled “It’s Round. I Checked.” In the chapter, he credits the origins of his flight to Jason Ehrlich, who had produced a reality TV show that Shatner had appeared on. Ehrlich, he recalled, was lobbying Blue Origin to fly Shatner while simultaneously lobbying Shatner that he should fly on New Shepard. Shatner said he was skeptical they would be interested in flying an actor, but eventually accepted a meeting with Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos at the company’s headquarters, where Shatner was impressed (that meeting is also featured in the documentary “Shatner in Space” last year.)

The prospect of flying in space languishes for a while because of flight delays—the initial meeting between Shatner and Bezos took place before the pandemic—but Shatner, buoyed by Ehrlich, thinks there’s a chance he could go on the first crewed flight. That doesn’t happen, but Ehrlich tells him a seat on the second might be possible. When that happens, he weighs the “wonder and thrill” of going to space against the risks, with the former winning out. “And so, I thought, I must go to space. Not because I was Captain Kirk, but because I’m alive.”

He skips ahead to the flight itself, where he makes clear that while the benefits of the flight outweigh the risks, those risks were at the forefront, as he worried about everything from the prospects of an explosion to being able to properly buckle into his seat for the five-g reentry. There is no shortage of melodrama for what turned out to be a routine flight. For example, when controllers tell the crew the countdown is briefly halted to check an engine anomaly, he is not reassured. “More importantly, why would they tell us that? There is a time for unvarnished honesty. I get that. This wasn’t it.” [Emphasis in original.]

| When controllers tell the crew the countdown is briefly halted to check an engine anomaly, he is not reassured. “More importantly, why would they tell us that? There is a time for unvarnished honesty. I get that. This wasn’t it.” |

When New Shepard launches, he says he’s less interested in experiencing weightlessness than looking out the window. He looks down at the Earth and then up into space, where that blackness surprised him. “Everything I had thought was wrong. Everything I has expected to see was wrong,” he said. “My trip to space was supposed to be a celebration; instead, it felt like a funeral.” (How different might his experience been had he flown at night, when the glare of the Sun would not have washed out the sky, revealing instead stars in sharper focus than in the best conditions on the ground?)

He later notes that he experienced the Overview Effect many other astronauts have reported, although perhaps more emotionally than most. “I wept for our planet,” he said he later told Bezos, fearing generations of environmental disasters to come. “Then Jeff let me in on his plan.” That plan, which Bezos has talked about publicly for years, is his long-term vision to move manufacturing and its environmental impact off Earth.

Shatner sounded receptive, but worried it would take too long. Nonetheless, he appeared to appreciate the flight, and is something of a fan of Bezos. “Jeff Bezos, I must say, is a misunderstood person,” he writes. “His excursion into outer space seems, on the surface, to be the excesses of capitalism shown off in a gaudy display of ego, and yet ego is not what has driven Jeff to space.”

And, for all his handwringing about the dangers of the flight, going to space on New Shepard was hardly the riskiest thing he did in the last few years: in the book’s introduction, he recalled scuba diving with sharks for a Shark Week episode. “To me, experiences must be felt. They must be lived. We need to reach out for love as well as fear if we want to stay vibrant.” Well, staying vibrant is the last thing Shatner has to worry about, whether it’s in the ocean or the edge of space.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Dennis Tito And Wife To Fly Aropund The Moon

Who wants to fly around the Moon?by Jeff Foust |

| “I’ve been wanting to go to the Moon since my first trip to space to the space station in 2001,” Tito said. |

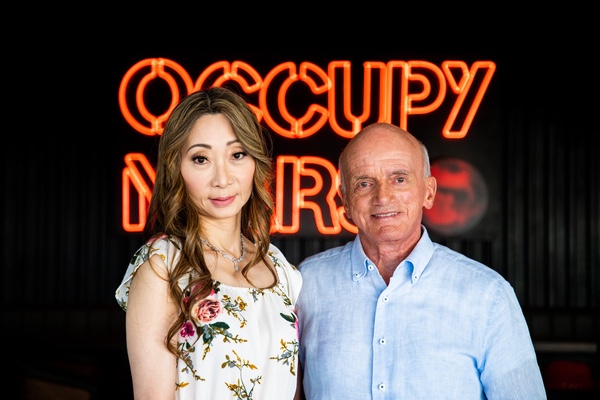

This time around, he is willing to be second in line. SpaceX announced last week that Tito and his wife, Akiko, had purchased tickets for a Starship flight around the Moon. The two would be joined by up to ten other people on the week-long flight, swinging around the Moon but not going into orbit or landing before returning to Earth.

“I’ve been wanting to go to the Moon since my first trip to space to the space station in 2001,” Dennis Tito said in a call with reporters a few hours after a carefully choreographed series of initial news reports about the trip. “So now, the adventure of traveling to the Moon and seeing it at close range, with my own eyes, is almost unimaginable.”

Tito hadn’t previously discussed that yearning for a lunar flight, at least not publicly. Despite being a pioneer in orbital commercial human spaceflight, he largely stayed behind the scenes, doing little in the way of advocacy or funding of commercial spaceflight initiatives. His biggest venture was Inspiration Mars, a short-lived proposal for a private human Mars flyby mission (see “A Martian adventure for inspiration, not commercialization”, The Space Review, March 4, 2013). His role in that, he said at the time, was as a sponsor and initial funder, and indicated no interest in going into space, on that mission or any other.

What changed, he said in the call, was the growth of SpaceX’s capabilities. “I’ve been following SpaceX on almost a daily basis, watching YouTube, for the last five years,” he said. “I could see that there was an opportunity with Maezawa for the first circumlunar mission and I started thinking about it.”

That was a reference to Yusaku Maezawa, a Japanese billionaire who, in 2018, announced he was buying a circumlunar flight on what was then known as BFR (officially Big Falcon Rocket, unofficially… something else) from SpaceX. Maezawa said he planned to fly a group of artists around the Moon.

The first meetings with SpaceX took place a little more than a year ago, when the company broached the possibility of flying Tito back to the ISS. “I certainly don’t want to go back to the space station. I don’t even want to orbit the Earth,” he recalled. “Then I thought about it and said I would be interested in going to the Moon.”

His wife—an engineer, pilot, and real estate investor—was with him at the meeting. “I looked over to Akiko and we had kind of a little eye contact and she goes, ‘Yeah, me too,’” he said. “That’s how it all began.”

Akiko Tito, also on the call, said she had been interested in space from a young age. “This mission is the first of many that will help humanity become multiplanetary and I’m so honored to be a part of it,” she said.

| “We have a lot of interest in this mission. We’re talking to many different customers,” Matthews said, describing the Titos as “anchor customers” for the flight. |

But while the Titos were happy to talk about the backstory of the mission and their excitement to be on it, they, and SpaceX, offered few details about the mission itself. The flight profile, Dennis Tito said, would involve launching a Starship into low Earth orbit, where it would meet up with a fuel depot version of Starship whose tanks had been filled by several other Starships—an approach similar to how SpaceX had described the lunar lander version of Starship it is developing for NASA’s Human Landing System (HLS) program. Once Starship’s tanks are topped off, it will fire its engines on a circumlunar trajectory, swinging around the Moon about 200 kilometers above the lunar surface then heading back. The overall trip would take about a week, including three days each way to and from the Moon.

SpaceX declined to give a schedule for the flight on the call, stating only it would come after Maezawa’s flight as well as the first crewed Starship launch, a test flight in Earth orbit that is part of the Polaris Program funded by billionaire Jared Isaacman. Those flights would be “pretty independent” from SpaceX’s work on HLS, said Aarti Matthews, director of Starship crew and cargo programs at SpaceX.

Matthews also said the company had not decided if the mission would launch from Starbase, SpaceX’s test site at Boca Chica, Texas, or from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where the company is building up a second Starship launch pad at Launch Complex 39A. Similarly, she could not say where the Starship would land at the end of the mission.

The sign behind them may say “Occupy Mars,” but Akiko and Dennis Tito have their sights set on a trip around the Moon. (credit: SpaceX) |

Dennis Tito declined to discuss how much he paid for the seats on the flight. “I don’t want to say anything about the cost. That’s not available publicly,” he said when asked for the price, either in absolutely values or relative to his 2001 trip to the ISS. Tito paid no more than $20 million for the ISS trip, and has an estimated net worth today of around $1 billion.

It will be up to SpaceX to fill the other seats on what the company says will be a 12-person flight. “We have a lot of interest in this mission. We’re talking to many different customers,” Matthews said, describing the Titos as “anchor customers” for the flight. “Without the vision you both have, this entire mission wouldn’t really be possible.” However, she didn’t say if SpaceX would fly the mission if it didn’t sell all the seats.

The other ten people would likely be paying customers. Asked if the Titos and other customers would be accompanied by a professional astronaut—a requirement NASA now has for private astronaut missions to the ISS—Matthews mentioned Dennis Tito’s previous spaceflight and Akiko Tito’s pilot experience. “We really couldn’t pick two better crew members,” she said.

“I would feel comfortable if there were no other people on board this mission,” Dennis Tito said. “I think I could easily handle it.” SpaceX didn’t provide much in the way of details on the training for the mission.

The Titos may have plenty of time to prepare for the flight no matter how quickly it sells the other seats. As currently scheduled, it will follow Maezawa’s flight, called “dearMoon,” but exactly when it flies is unclear. Last year, he kicked off a competition to select the eight people who would accompany him on the flight, then scheduled for 2023.

| “There’s going to be a lot of flights, a lot of testing,” Tito said of Starship. “I think actually the vehicle will be better tested when we fly than even the Soyuz was when I flew 21 years ago.” |

However, there have been no updates on the process of selecting that crew since September of 2021—more than a year ago—when dearMoon posted on its website that those people going on to the next (and possibly final) round of the selection process had completed medical checkups. “Those who have not gone that far, we thank you for applying & hope for your continuing support,” the website states. The dearMoon project did not respond to a request for comment last week on the status of the crew selection effort or the schedule for the mission.

Even if Maezawa had a crew ready, though, a flight around the Moon in 2023 seems highly unlikely, in part because Starship has yet to even attempt its first orbital launch. Progress on vehicle development and testing has been going slowly, at least relative to the steady stream of low-altitude suborbital Starship tests in late 2020 and early 2021 that culminated with a successful launch and landing of the vehicle.

Just before SpaceX announced the deal with the Titos, the company had stacked a Starship vehicle, including the Super Heavy booster, on the pad at Boca Chica for testing, although a launch attempt is not imminent. “We are proceeding very carefully,” Musk tweeted October 16. “If there is a RUD on the pad, Starship progress will be set back by ~6 months.” A RUD is “rapid unscheduled disassembly,” aka an explosion.

It’s possible that the first Starship orbital launch, a test flight, won’t be completely successful, given the track record from past Starship tests. That would further push out crewed flights, be they for space tourists or NASA’s HSF programs.

Dennis Tito, whose first flight to space was on a Soyuz spacecraft that had flown dozens of crewed missions over more than three decades by that point, was not concerned about going on a vehicle yet to reach orbit. He said that by the time he takes his trip to the Moon, he expects Starship expects to have performed “hundreds” of launches, a figure that presumably includes uncrewed flights like launches of Starlink satellites.

“This is not going to happen in the near term,” he said of his mission. “There’s going to be a lot of flights, a lot of testing. I think actually the vehicle will be better tested when we fly than even the Soyuz was when I flew 21 years ago.”

SpaceX’s Matthews offered similar confidence that Starship will be ready to take people around the Moon when the time comes—whenever that time is. “We are confident that we will have this vehicle fully tested out and ready to go by the time we fly this mission,” she said.

That should give SpaceX plenty of time to determine if there are enough people, at whatever price they’re charging, to fill up a Starship for a trip around the Moon. Given Starship’s prospects for much lower launch costs, it’s conceivable a flight around the Moon might cost, on a per-seat basis, somewhere in the same ballpark as a flight to the ISS, which is around $50 million today. For some space tourists, going around the Moon might be worth a modest premium over yet another trip to the ISS.

It remains uncertain if this is really a sustainable business or a one-off (or two-off, if Maezawa’s flight is included) flight around the Moon. If the former, Dennis Tito might again be a commercial human spaceflight pioneer.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Monday, October 17, 2022

Mission Accomplished!-DART Spacecraft

Mission Accomplished

NASA’s planetary defense mission was a smashing success, the Associated Press reported.

The agency’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft was able to divert the orbit of the 525-foot-long Dimorphos asteroid after crashing against the space rock last month.

The DART mission is part of NASA’s efforts to protect Earth from world-ending asteroids or comets. Planetary defense scientists suggested that it would be safer to shift the orbits of these celestial bodies, instead of bombing them, which can result in smaller space rock debris hitting our world.

The space agency selected Dimorphos, which orbits around its parent asteroid, Didymos. Neither of them poses a threat to Earth.

Last year, NASA launched the vending machine-sized DART, which later slammed into Dimorphos at a speed of 14,000 miles per hour on Sept. 26. The impact left a crater in the asteroid and created a comet-like trail of dust and rubble stretching thousands of miles.

Scientists closely observed how the crash impacted Dimorphos and the results exceeded their expectations. Before the impact, the smaller asteroid circled its parent for 11 hours and 55 minutes. Researchers expected the hit to shorten the asteroid’s orbit by 10 minutes, but they found that the impact reduced it by 32 minutes.

They added that the smash also left Dimorphos wobbling a bit and its orbit will never go back to its original location.

“This mission shows that NASA is trying to be ready for whatever the universe throws at us,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson.

Friday, October 14, 2022

Tuesday, October 11, 2022

Monday, October 10, 2022

Making A Modern Military Force

Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond, the first chief of space operations of the Space Force, speaking at a conference in September. (credit: US Air Force photo by Eric Dietrich) |

Making a modern military service

The US Space Force knows it needs to be fast, lean, and agile, but how?

by Coen Williams and Peter Garretson

Monday, October 10, 2022

The Space Force needs new individual and organizational frameworks. Simply applying the tools of the last century will not be effective. This means recreating the space-minded joint warfighter as the Guardian-Designer, enabling increased freedoms to make changes to software, hardware, and operations. Advancing US Space Force (USSF) organizations through the OADE Loop is critical to the creation of the nation’s first 21st century military branch.

In 1989, Carl Builder published a provocative analysis of the Army, Navy, and Air Force with the book The Masks of War. In it, he describes a phenomenon he calls the “altar of worship.” The Air Force worships at the altar of technology, the Navy worships independence of action on the sea, and the Army worships its own relationship with that which it originates from, the American people. With the Space Force’s nascent separation from the Air Force, its own “mask” can be roughly identical to that of its mother service, including its preferred altar of worship, but it must evolve from worshipping technology as an end towards the effective and economical application of technology and organizations.

| The Guardians have yet to find their new North Star; the definition of a digital and agile service remains nebulous. The USSF needs to be clear about what it proposes to change and provide easily understood frameworks to get there. |

Organizationally, the US military has worshipped different forms of organizational management: General George Marshall developed a first-rate military logistics structure and fighting culture in order to win World War II, and Colonel John Boyd designed the perfect framework to imagine tactical decision making, the Observe-Orient-Decide-Act (OODA) loop. The seminal work of John Kotter on leading and strategizing organizational change, getting from “A” to “B”, follows a clear eight-step process, but getting to “B” and staying there for 20 or more years is not enough for the USSF.

The Space Force, the only American military service to stand up since 1950, has an opportunity to build off these legacies and redefine its Guardian (the USSF’s version of “soldier” or “sailor”) culture and military organizations for the 21st century. Thankfully, this challenge has not gone completely unanswered.

The USSF has recently published several documents that consolidate bold new ideas from across the service. The Guardian Ideal highlights the ideal characteristics and plans for the USSF’s talent management program. However, its proposed Guardian Commitment focuses entirely upon traditional understandings of “Character, Connection, Commitment, and Courage.” Similarly, the Chief of Space Operations Planning Guidance states the importance of “empower[ing] a lean and agile service” and of the need to move fast.

Within these pages, the Guardians have yet to find their new North Star; the definition of a digital and agile service remains nebulous. The USSF needs to be clear about what it proposes to change and provide easily understood frameworks to get there. The Guardian-Designer and an evolution of the OODA loop for organizational change, the OADE loop, provide simple frameworks for meeting this critical shortcoming.

The Guardian-Designer

The Guardian-Designer concept is simple to understand: Guardians should have the freedom to make changes to the software, hardware, or operations of the systems that they manage. Whether this be space-, ground- or cyber network-based systems, Guardians are currently held back by existing regulations and authorities in their need to evolve to meet existing and future needs. Guardians should, rather than maintaining status-quo systems and operations for decades, seek to craft or acquire new tools in the goal of making their current systems and operations irrelevant.

| Created for the sole purpose of approaching existing problems in different ways, the USSF cannot execute this directive without some form of fundamental shift in acquisitions, sustainment, and culture. |

Meeting new capability needs is currently governed by the confusing DOTmLPF-P acronym. Rather than delegating authority and resources at the lowest levels to solve challenges in the most precise manner, DOTmLPF-P forces our Guardians to abide by decisions made at the top of the chain of command, decisions that unintentionally deemphasize new innovations, acquisitions, or creations made at the tactical level. The leadership of the USSF needs to provide, and lobby for, the structured authorities for Guardian-Designers to make needed changes at the tactical level.

The OADE Loop

The freedom to enact change should not stop at the individual Guardian, organizations (flights, squadrons, deltas, etc.) must be at the liberty to rapidly iterate upon their own structure and focus. To worship at the altar of “freedom to focus on tomorrow,” the USSF must learn to change more quickly and effectively than the changes of the world and potential adversaries. By maximizing the freedom of any internal organization to focus on the next larger canvas of problems, the USSF will learn to iterate the Observe-Automate-Design-Execute loop as it has learned agile software development models within specific organizations.

- Observe expanding opportunities

- Automate current operations wherever possible

- Design a new organizational change strategy

- Execute the new organizational change strategy

The USSF is currently attempting to provide itself the authorities to perform such a task, but any proper bureaucrat will understand the difficulty of rapidly and effectively executing such a loop. This is precisely the point: the USSF of the future will be measured by the speed at which it—and its organizational components—can evolve at a timely rate, and then do it again. All Star Trek futures aside, the Space Force must adopt a 21st century approach to the problems of today and of our progeny. Supra Coders are a start, but increased education means little when increased authorities do not keep pace.

Fast, lean, and agile means nothing when unsubstantiated. Created for the sole purpose of approaching existing problems in different ways, the USSF cannot execute this directive without some form of fundamental shift in acquisitions, sustainment, and culture. Marshall enabled sustained logistics, Boyd closed the loop on tactical decision making, but Guardians must learn to craft and develop their own future. As Guardian-Designers, following OADE in their desire to focus their human intellect on ideal of beating the future to the punch, Guardians can stay ahead of change, by creating it.

Coen Williams is a US Space Force officer currently stationed at Vandenberg Space Force Base. Coen received a Master in Public Policy from the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, and Bachelors in Astronautical Engineering and Applied Math from the US Air Force Academy. Peter Garretson is a Senior Fellow in Defense Studies at the American Foreign Policy Council and a strategy consultant who focuses on space and defense. He is the coauthor of Scramble for the Skies The Great Power Competition to Control the Resources of Outer Space and the host of AFPC’s Space Strategy Podcast.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

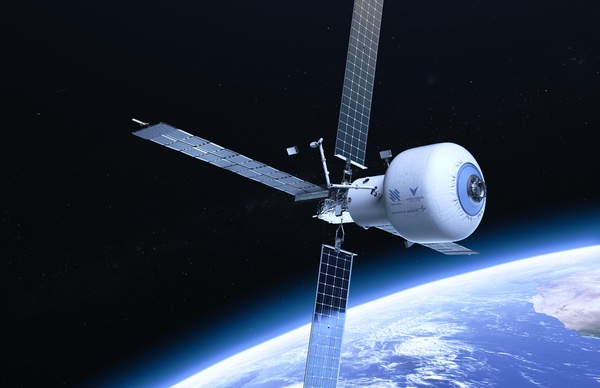

Commercial Space Stations-Labs or Hotels?

Voyager Space used the IAC to announce research partnerships for its Starlab commercial space station, but also an agreement with Hilton to design accommodations for it. (credit: Voyager Space) |

Commercial space stations: labs or hotels?

by Jeff Foust

Monday, October 10, 2022

One of the more unusual side events associated with last month’s International Astronautical Congress (IAC) took place not at the Paris Convention Center but instead several kilometers away at the historic Paris Observatory. The purpose of the event was not related to astronomy—although one could look through telescopes there on the clear fall evening—but instead something quintessentially French: champagne.

| “The difference between animals and humankind is culture,” said Giron. “We wanted to be able to celebrate conviviality in space.” |

It was at that event that Maison Mumm announced a partnership with commercial spaceflight company Axiom Space to fly its champagne into space. That partnership was more than just grabbing a bottle of Mumm and sticking it in the cargo hold on a future Axiom mission. Instead, Mumm worked with a design firm and the French space agency CNES to develop a special bottle, featuring aerospace-grade aluminum and a “perfectly reliable stainless steel opening-closing mechanism” that complies with both spaceflight safety regulations and those governing champagne in France. The champagne itself, Mumm Cordon Rouge Stellar, is a special blend developed for this project, featuring “notes of ripe yellow fruit and vine peach, but also dried fruit, hazelnut and praline,” the company said.

At the event, with terrestrial Mumm champagne flowing freely from traditional bottles, officials with Maison Mumm, Axiom, and others talked up the partnership. But why go through all the effort to send champagne to space? For César Giron, president of Maison Mumm, it was inevitable. “The difference between animals and humankind is culture,” he declared, pointing out Mumm champagne was part of the first French expedition to Antarctica in 1904. “We wanted to be able to celebrate conviviality in space.”

“Life is about experiences. It is about culture. It is about enjoying yourself in various ways,” said Michael Suffredini, CEO of Axiom Space.

So when will the champagne fly in space? “It’s our intent to fly it on our next flight,” Suffredini said, referring to the Ax-2 mission the company plans to fly to the International Space Station next spring. “We’ve got some work to do to sort that out.”

Flying the champagne, though, isn’t the same as drinking it. Consumption of alcohol is not allowed, at least on the US segment of the ISS. “Well, one of the things that Axiom is known for is kind of pushing the limits a little bit with the government,” he said. “We’ll take it a step at a time. We’ll fly the bottle and then talk about how we’ll do our testing.” He added he didn’t think the company would have to wait until it starts adding its modules to the ISS around the middle of the decade to, ah, test the champagne.

Axiom Space CEO Michael Suffredini (center) speaks about his partnership with Maison Mumm to fly its champagne on future Axiom missions. (credit: Maison Mumm) |

The Mumm-Axiom partnership was not the only announcement the week of the conference dealing with commercial space stations and hospitality. A day earlier, Voyager Space announced it would work with Hilton on its Starlab commercial space station concept. Hilton will be the “official hotel partner” for the station, helping design accommodations on the station. The companies will also work together on “the ground-to-space astronaut experience” and other tourism-related efforts.

The announcement brought back memories of Barron Hilton’s proposals in the 1960s for a “Lunar Hilton” and the cameo a Hilton Hotel on a rotating space station played in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The press release about the partnership mentioned Hilton’s “storied history with space” but, curiously, linked instead to a project less than three years ago when Hilton’s DoubleTree chain flew, and baked, cookies on the ISS.

But the conference and associated events illustrated a dichotomy regarding marketing of commercial space stations. On the one hand, the stations are being touted as destinations for tourists, with accommodations by Hilton and champagne by Mumm. The same companies, though, are also emphasizing those stations as destinations for research and opportunities for countries, not wealthy individuals, to live and work in space.

| “It is very, very important not to break it, because that is the last thing you want to break on the station,” said Kavandi of the toilet. “You do not want that to break.” |

Voyager, for example, announced signing memoranda of understanding (MOUs) with five Latin American space agencies and organizations to study flying payloads on Starlab and helping plan use for the station and its George Washington Carver Science Park. That science park will have a terrestrial component that the company announced will be established at the Ohio State University, starting in an agricultural engineering building and later moving to its own building at the university’s Aerospace and Air Transportation Campus.

Axiom Space, meanwhile, used the conference to announce several agreements to fly people or payloads. Perhaps the biggest was the announcement of a deal with the Saudi Space Commission, Saudi Arabia’s space agency, to fly two Saudi astronauts on a future Axiom mission. The two astronauts would fly next year, the Saudi Space Commission said, but did not disclose how they would be selected other than that one of them would be a woman.

Axiom also provided few details about flying the Saudi astronauts amid speculation they could go on next spring’s Ax-2 mission; the company has not announced who will take two of the four seats on that Crew Dragon mission to the ISS. “This partnership highlights Axiom Space’s profound commitment to expand human spaceflight opportunities to a larger share of the international community, as well as to multiply scientific and technological development on Earth and in orbit,” Axiom CEO Suffredini said in a statement.

The Saudi agreement was one of several Axiom announced during the conference. It signed an agreement with the government of Turkey to send the first Turkish astronaut to space on a future Axiom mission, and announced MOUs with Canada and New Zealand for research activities; the agreement with the Canadian Space Agency also opened the door to flying Canadian astronauts on Axiom missions. In July, Axiom signed an MOU with Hungary to study opportunities such as flying a Hungarian astronaut.

Orbital Reef, the commercial space station project led by Blue Origin and Sierra Space, also seems to be straddling the research and tourism markets. During a session of the IAC, Janet Kavandi, president of Sierra Space, discussed the importance of having a staff of professional astronauts running the station, taking care of the day-to-day maintenance of the facility. “We’re going to have people that have to maintain the space station so that the people that are up there doing that incredible stem cell research, the biological research,” she said, “don’t need to be bothered with the toilet, or the IT system when it goes down.”

But the companies are also thinking about what’s needed for the station to support tourism. Kavandi cautioned not to compare Orbital Reef with a five-star terrestrial resort. “It’s going to be a little bit different in space,” she said, because there will be a smaller staff. “Part of the training that I have in mind is to limit expectations, but also to realize that what you’re going to get for that experience is more than you can imagine.”

Those differences between Orbital Reef and a terrestrial hotel extend to the bathroom, which will be “rudimentary” in space. “It is very, very important not to break it, because that is the last thing you want to break on the station. You do not want that to break.”

“I am very keen as a community to develop food as an experience,” said Brent Sherwood, senior vice president of advanced development programs at Blue Origin, at the session. Tourists, he suggested, might want to “eat like astronauts” for one day of their stay. “But for the other days, I think we need to learn how to actually cook in space. And nobody knows how to do that.”

The effort by companies proposing commercial space stations to balance tourism and research may in part be good public relations. Millionaires flying to space is a big target for criticism of wasteful spending. Even Axiom’s partnership with Mumm to fly champagne to space generated pushback: “Space tourism hits a new low,” tweeted Michael Byers, co-director of the Outer Space Institute at the University of British Columbia, in response to the announcement.

| “It’s unclear if the market can support four competitors, or two competitors. We don’t know, really,” said Dittmar. |

Developing commercial space stations to support work like biomedical research, though, is easier to build support for. The same may be true for giving more countries opportunities to send people into space, although that may come with geopolitical complications. (It will be interesting to see if that happens with the Saudi astronauts; at IAC, a bid by the Saudi government to host the 2025 IAC in Riyadh that appeared to be the frontrunner encountered a backlash from International Astronautical Federation members, who instead selected Sydney, Australia.)

Another reason may be more practical: companies just aren’t sure where the demand will be for commercial space stations, beyond NASA’s stated interest in transitioning research currently done on the ISS to such stations, and are covering their bases to be ready to support research or tourism as they emerge.

During one panel discussion at IAC, an Axiom executive offered a cautionary note. “I think we’re going to have to be really hard-headed about business cases, and I don’t think we’re there at all,” said Mary Lynne Dittmar, chief government and external relations officer at Axiom Space.

Just how much demand there is for research, tourism, or other applications is uncertain, she said. “It’s unclear if the market can support four competitors, or two competitors. We don’t know, really.”

NASA is currently supporting four teams—Axiom, Blue Origin/Sierra Space, Northrop Grumman and Voyager—for commercial space station studies or, in Axiom’s case, access to an ISS port for attaching commercial modules. Few, though, think that all four will be able to follow through, technically and fiscally, on their station concepts.

“There’s going to be some hard choices that need to be made,” Dittmar said of narrowing down the field of space station companies, “and they will need to be made sooner than most people are prepared to make them.”

Some, though, hold out hope that all four can continue. “I hope there’s enough of a market for all of us to succeed,” said Andrei Mitran, director of strategy and business development at Northrop Grumman, during another IAC session. “We are looking at how do we make the pie bigger,” he added. “Otherwise we could kill this market.”

So, perhaps, by the end of the decade tourists on a commercial space station might be sipping their Mumm champagne from specially designed glasses while floating by a window, watching the Earth below. On the other hand, it might be researchers who are breaking out the bubbly to celebrate a milestone in a research project on a commercial station. In either case, where people go, champagne will follow.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

Review-A Traveler's Guide To The Stars

|

Review: A Traveler’s Guide to the Stars

by Jeff Foust

Monday, October 10, 2022

A Traveler’s Guide to the Stars

by Les Johnson

Princeton Univ. Press, 2022

hardcover, 240 pp., illus.

ISBN 978-0-691-21237-1

US$27.95

Tucked away on the inside of the adapter that connects the Orion spacecraft to the upper stage of the Space Launch System are ten cubesats, patiently awaiting launch on the Artemis 1 mission. One of those ten is Near Earth Asteroid (NEA) Scout, a NASA cubesat that will, after deployment, unfurl a solar sail and use that to send the spacecraft on a flyby of a near Earth asteroid in two years. NEA Scout was intended as a technology demonstrator for larger solar sails, explained Les Johnson, principal investigator for the solar sail part of the mission at NASA Marshall, during a talk at the Conference on Small Satellites in Utah in August.

Johnson’s vision, though, goes far beyond solar sails for cubesats. He has been involved for more than two decades on efforts related to interstellar travel, dating back to managing a short-lived NASA project on interstellar propulsion at the turn of the century. “I became a convert” to the field by that time NASA ended that project, he writes in the preface of his new book, A Traveler’s Guide to the Stars. “I came to believe that going to the stars is something that can actually be done.”

| “Crossing the vast distances from Earth to the stars will require revolutionary advancements in spacecraft propulsion,” he writes. |

Johnson uses the book to make the case that interstellar travel can be done, even though it will be exceptionally difficult. While he offers some discussion of where to go, thanks to explosion of exoplanet discoveries, and why to go there, the heart of the book is on technology: how to get there. Conventional chemical propulsion is off the table, so he examines the various alternatives, like fission, fusion, and antimatter. He also explores different types of sails, including the laser-propelled lightsails being studied by the Breakthrough Starshot project.

The news isn’t terribly encouraging. Johnson estimates that, for a vehicle designed to travel at 10% the speed of light, the minimum acceptable specific impulse—a measure of the efficiency of the propulsion system—is 400,000 seconds, about 1,000 times higher than the best chemical rocket engines. Most other alternatives also fall short of this threshold, with only sails and some antimatter and continuous fusion systems exceeding it. However, those systems offer only small accelerations. “Crossing the vast distances from Earth to the stars will require revolutionary advancements in spacecraft propulsion,” he writes.

Yet, he is undeterred by that challenge, devoting one chapter to other design issues of interstellar vehicles, from communications and navigation to life support for crewed spacecraft, all on the assumption that the propulsion problem is solved, somehow. He embraces the challenge: “if we are to go to the stars, then we need to think BIG,” he writes, grappling with enormous distances and energies, as well as schedules and costs.

It's unclear that the reader will come away with the same enthusiasm for interstellar travel. Instead, the magnitude of the challenge may simply seem too daunting for our current level of technology, like asking the Montgolfier brothers to build an SR-71. One must start somewhere, proponents will argue, but without near-term milestones, sustaining long-term progress will be difficult. A decade ago, for example, there was considerable enthusiasm around the 100-Year Starship initiative, seeded with DARPA funding, to study issues associated with interstellar travel with a century-long time horizon. But that project has faded: the last press release on its website was posted five years ago (although it is holding a “100 Year Starship Annual Marquee Public Happening” in Nairobi next year, so perhaps the organization was simply testing suspended animation technology for interstellar travel.)

Efforts like solar sails might be one way to achieve that near-term progress to sustain work on longer-term interstellar projects, but even that is not simple. Johnson noted at the smallsat conference in August that NEA Scout was intended to be a technology precursor for Solar Cruiser, a heliophysics mission that would have used a larger sail to maneuver around the Earth-Sun L1 point. However, NASA declined to confirm that mission for development, citing technical problems with the spacecraft. And NEA Scout itself remains on the SLS, waiting for a launch now delayed to at least mid-November. When getting off the planet remains difficult, it’s hard to focus on getting out of the solar system.

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Sunday, October 9, 2022

Thursday, October 6, 2022

Celestial Clash

Celestial Clash

NASA’s Cassini space probe collected a myriad of data about Saturn before its mission ended in 2017.

Now, that data is helping scientists learn more about the planet and how it got its fascinating rings, Science Magazine reported.

Past research has shown that the water-ice rings encircling Saturn are more than 100 million years old. Their formation, however, has been a topic of speculation.

In a new study, a research team initially studied Saturn’s very peculiar 27-degree tilt of its spin axis.

The spin axis has surprised scientists because the planet was supposed to have a small tilt when it first formed billions of years ago – almost the same as Jupiter.

Instead, past research has shown that the spin axis has been affected by the gravitational effects of another planet, Neptune, as well as Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, drifting away from the planet – a process that continues to this day.

But researchers observed that Saturn and Neptune were even then not entirely in sync, and they set on determining how this happened. They ran hundreds of simulations of Saturn’s system, including some involving a hypothetical long-lost moon about the size of Iapetus, the planet’s third-largest satellite.

From 390 simulations, 17 of them showed that this moon – named Chrysalis – approached the gas giant about 160 million years ago and caused this orbital nudge.

Eventually, Saturn’s gravitational forces shredded Chrysalis millions of years ago and resulted in the iconic planetary rings.

Still, the authors acknowledged that more research is needed to determine if the cataclysmic event led to the eye-catching celestial phenomenon.

A Ukrainian "Hit Team" Carried Out A High-level Assassination in Moscow!

Recently a car bomb went off in Moscow. The intended target was a man known as "Vladimir Putin's philosopher." Sadly, his 27-year-old daughter Darya Dugina was killed instead. The conventional wisdom was that Russian dissidents carried out the assassination. It now comes to light that a Ukrainian "hit team" had sneaked into Russia and carried out the "hit."

This operation comes right

out of the playbook of the Israeli Mossad. Many years ago, I wrote the

biography of a Mossad agent. He talked in generalities. I found a disgruntled

former Mossad agent living in Toronto who filled in all the blanks. I came away

with a phenomenal knowledge of the Mossad and the deepest respect for this

agency.

We all have heard

stories about the fictional British agent James Bond. He had a license to kill.

British and US intelligence agencies deny that any agents have such a license

to kill. (Who knows what the truth is???)

When I wrote the book, I found

that 12 Mossad agents truly had a license to kill. They were divided into three

4-person teams known as Kidon teams.

In extraordinary cases, the

execution of a very dangerous person or persons is deemed necessary. A death

warrant must be signed by the Prime Minister of Israel and the Chief Justice of

the Israel Supreme Court. A Yarid team is dispatched to put the subject under

long and careful observation. Once the habits and movements of the subject are

known, a Kidon team is dispatched to carry out the execution.

A lot of you will

find such practices morally abhorrent. Please bear in mind that the US,

Britain, and I suspect Russia use drones to assassinate very dangerous

people like terrorists.

When the car bomb went off

in Moscow, it sent shockwaves throughout the Kremlin and all the way up to

Putin. Many of you have heard the saying: "You can run, but you just can't

hide!"

Wednesday, October 5, 2022

Sputnik's Affect On Vanguard

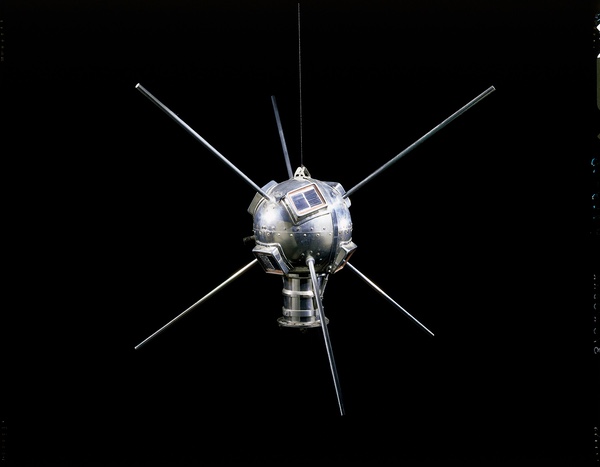

A replica of the Vanguard satellite. The launch of Sputnik caused engineers working on Vanguard to turn their attention to tracking the satellite. (credit: National Air and Space Museum) |

Sputnik’s effect on Vanguard

by Richard Easton

Monday, October 3, 2022

Sputnik 1 was launched on October 4, 1957. The strong reaction from the West showed Soviet dictator Nikita Khrushchev that space could contribute to soft power competition in the Cold War.

| Roger says, “They launched Sputnik.” And I said, “Good, now we know what can be done.” He said, “You don’t understand; we’ve got to track it.” And I said, “Can I eat supper first?” |

It also had an effect on nascent satellite programs in the United States, like Vanugard, as Marty Votaw recalled. After college in 1947, Martin Votaw worked at the Wave Propagation Research branch at the Naval Research Lab for three years. He then transferred to the Rocket Development branch to work for Roger Easton (my father) and made microwave transmitters for three Viking rocket launches. When the Vanguard program was approved, Votaw was assigned to work on ground antennas for receiving telemetry and tracking signals. He also worked on the small Vanguard 1 satellite.

Marty Votaw offered his recollections at the 50th anniversary of Vanguard 1 in 2008:

The Vanguard program was run on paid overtime from the beginning of the program. On Wednesday [October 2, 1957] at work, a memo came out that said there will be no paid overtime after Friday. And I thought “Phew!” we are going to get some time off.

And Friday came, I went home from work tired, and we had company that night. I sat down to dinner and the phone rang. And Roger says, “They launched Sputnik.” And I said, “Good, now we know what can be done.” He said, “You don’t understand; we’ve got to track it.” And I said, “Can I eat supper first?” He said, “Well, yeah, but come back right afterwards.”

And we worked the next three days without going home. We would go to Blossom Point [where the nearest Minitrack station was located], we made 40 MHz antennas [Vanguard was going to transmit at the IGY standard of 108 MHz whereas Sputnik1 transmitted at 20 and 40 MHz], we had to set up new antennas for each of the Minitrack sites—just a dipole in each one—and we had to run the cables, and these things are a 100 yards apart, or something. They had just plowed the fields to get rid of the weeds and it had rained and it was mud. We would go out and work and get these cables laid and get the antennas stuck in the ground. We would get tired and somebody would bring us food, and we would eat and we would go back and work some more. Then, we would get tired. We would come back and take our jackets off and roll them up for pillows, laid down on the floor of the trailer or the house, or whatever it was, and we would sleep a while. And after three or four hours we would wake up, put our coats on again, and go out and do some more.

And we finally got antennas hooked up and Vick Symus, he was the receiver specialist, so he had to take a mini-track receiver and he had put in a multiplier to get the 40 MHz up to 108. So, he got that done, so we had receivers ready, and we began tracking the signal as it came over. And we would get these long strip charts and Roger would say, “Come on, let’s take them to the computing place.” IBM had set up a special computer center and we would go and knock on the door and they wouldn’t let us in, but they would take the records. As I remember, we did that for two weeks. And, after three days, we got to go home and take a shower and then we went back to work.

So, we were working hard throughout the program and there was never any unpaid overtime. The Sputnik launch overtook the memo. So, the stories about a space race arrived in the newspapers and it was not generated by anybody at NRL. It was not supported by anyone at NRL. NRL’s responses were always based on the program inside and they were always full speed ahead. So, the space race is not a subject that fits into an NRL discussion. Period.

There is speculation that the Eisenhower Administration let the Soviets launch the first satellite since it made clear that space was outside any country’s airspace. Marty’s statement makes it clear that this as not the perspective of Vanguardians. Milt Rosen headed up Project Viking (not to be confused with the later NASA program) and was the technical head of Project Vanguard. His wife Sally came with the name Project Vanguard. She told me in 2009 that she was in Paris with Milt when Sputnik was launched. Their Parisian friends immediately made the connection between launching a satellite and using the rocket as an ICBM.

Thus, there was no conspiracy to allow the Russians to launch first. After Sputnik 2 was launched in November 1957 with a dog Laika onboard, Vanguard TV-3 blew up and was dubbed Flopnik. Von Braun’s team launched the first American satellite, Explorer 1, in January 1958. My father tinkered with the Vanguard 1 satellite on our dining room table. It was launched on March 17, 1958, and is the oldest human object in space today.

Richard Easton (winnetkaelm@comcast.net) has degrees from Brown University and The University of Chicago. He works as an actuary for an insurance organization in Irving, Texas. He is the coauthor of GPS Declassified: From Smart Bombs to Smartphones.

Review of The Whole Truth

|

Review: The Whole Truth

by Jeff Foust

Monday, October 3, 2022

The Whole Truth: A Cosmologist’s Reflections on the Search for Objective Reality

by P. J. E. Peebles

Princeton University Press, 2022

Hardcover, 264 pp.

ISBN 978-0-691-23135-8

US$27.95

Three years ago, cosmologist Jim Peebles won a share of the 2019 Nobel Prize in Physics for “theoretical discoveries in physical cosmology,” as the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences described it. Peebles spent his career working on models to explain the formation of the universe, from the cosmic microwave background to the roles played by dark matter and dark energy. His work, the announcement of the prize stated, “laid a foundation for the transformation of cosmology over the last fifty years, from speculation to science.”

It was also, in his view, inevitable. “But given the state of technology in 1960, and the relative stability of the culture of science and society that went with it,” he writes in the book The Whole Truth, the “standard model” of the universe known as lambda cold dark matter, or ΛCDM, “seems sure to have been discovered.”

The book is partially an examination of some of those key topics in cosmology, from general relativity to the cosmic microwave background, and how understanding of them changed over the decades (including the roles he played in them.) The book, though, is also a more general examination of how science in general, and physics in particular, gets done.

| There were multiple paths to getting to this standard cosmological model, he argues, with many Merton multiples along the way. |

The book starts off with the latter, examining some philosophical questions about how science works. This includes theories that are accepted as “good enough approximations to reality” because “their applications yield successful predictions of situations beyond the evidence from which the theories were constructed.” He also notes that in science, including in cosmology, there is a tendency for discoveries or new models to be made independently by two or more people at the same time, something Peebles dubs “Merton multiples” after sociologist Robert Merton, who discussed it in an article more than 60 years ago.

Peebles then examines the development of cosmology, which evolved dramatically over the course of his career. For example, while Einstein’s theory of general relativity was “proven” by measurements of the movement of stars during a 1919 solar eclipse, the evidence supporting it was still weak for decades afterward. Only improved measurements of gravitational redshifts starting in the 1960s removed that uncertainty, providing ever-increasing precision to the predictions of general relativity.

He does the same with other aspects of cosmology, including the Big Bang and the development of the ΛCDM model. In the book’s final chapter, he explains his confidence that the model would exist today even if the specific steps that led to its development were not followed. For example, if Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson had not detected the cosmic microwave background, the signature of the Big Bang, at Bell Labs, a group at Princeton likely would have done so within a year. There were multiple paths to getting to this standard cosmological model, he argues, with many Merton multiples along the way.

That gives him confidence that the current model is correct, at least based on the knowledge we have today about the universe. “And let us note that this is what we would expect if our present physical cosmology is a good approximation to objective reality,” he says of the model, “not a social construction.”

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.

|

Review: The Whole Truth

by Jeff Foust

Monday, October 3, 2022

The Whole Truth: A Cosmologist’s Reflections on the Search for Objective Reality

by P. J. E. Peebles

Princeton University Press, 2022

Hardcover, 264 pp.

ISBN 978-0-691-23135-8

US$27.95

Three years ago, cosmologist Jim Peebles won a share of the 2019 Nobel Prize in Physics for “theoretical discoveries in physical cosmology,” as the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences described it. Peebles spent his career working on models to explain the formation of the universe, from the cosmic microwave background to the roles played by dark matter and dark energy. His work, the announcement of the prize stated, “laid a foundation for the transformation of cosmology over the last fifty years, from speculation to science.”

It was also, in his view, inevitable. “But given the state of technology in 1960, and the relative stability of the culture of science and society that went with it,” he writes in the book The Whole Truth, the “standard model” of the universe known as lambda cold dark matter, or ΛCDM, “seems sure to have been discovered.”

The book is partially an examination of some of those key topics in cosmology, from general relativity to the cosmic microwave background, and how understanding of them changed over the decades (including the roles he played in them.) The book, though, is also a more general examination of how science in general, and physics in particular, gets done.

| There were multiple paths to getting to this standard cosmological model, he argues, with many Merton multiples along the way. |

The book starts off with the latter, examining some philosophical questions about how science works. This includes theories that are accepted as “good enough approximations to reality” because “their applications yield successful predictions of situations beyond the evidence from which the theories were constructed.” He also notes that in science, including in cosmology, there is a tendency for discoveries or new models to be made independently by two or more people at the same time, something Peebles dubs “Merton multiples” after sociologist Robert Merton, who discussed it in an article more than 60 years ago.

Peebles then examines the development of cosmology, which evolved dramatically over the course of his career. For example, while Einstein’s theory of general relativity was “proven” by measurements of the movement of stars during a 1919 solar eclipse, the evidence supporting it was still weak for decades afterward. Only improved measurements of gravitational redshifts starting in the 1960s removed that uncertainty, providing ever-increasing precision to the predictions of general relativity.

He does the same with other aspects of cosmology, including the Big Bang and the development of the ΛCDM model. In the book’s final chapter, he explains his confidence that the model would exist today even if the specific steps that led to its development were not followed. For example, if Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson had not detected the cosmic microwave background, the signature of the Big Bang, at Bell Labs, a group at Princeton likely would have done so within a year. There were multiple paths to getting to this standard cosmological model, he argues, with many Merton multiples along the way.

That gives him confidence that the current model is correct, at least based on the knowledge we have today about the universe. “And let us note that this is what we would expect if our present physical cosmology is a good approximation to objective reality,” he says of the model, “not a social construction.”

Jeff Foust (jeff@thespacereview.com) is the editor and publisher of The Space Review, and a senior staff writer with SpaceNews. He also operates the Spacetoday.net web site. Views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.